Conventional wisdom suggests that access to financial services such as banks and bond markets, providing savings and borrowing instruments, allows smoothing consumption over

How does financial inclusion affect consumption smoothing in emerging economies? Volatile consumption, reflecting the fact that people are unable to maintain an optimal level of consumption over their lifetime, causes welfare loss in a society. Higher the volatility of consumption, greater is the welfare loss. Conventional wisdom suggests access to financial services such as banks and bond markets, providing savings and borrowing instruments, allows people to smooth consumption over their lifetime. In good times, part of income, over and above what is needed to maintain the consumption level can be saved in saving accounts in banks, and/or through buying bonds. In bad times, these savings can be used to preserve the level of consumption. Highly volatile consumption indicates lack of these channels facilitating consumption smoothing.

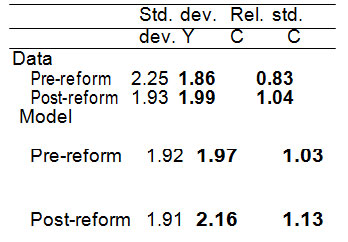

Relative consumption volatility – which is consumption volatility relative to income volatility - is an indicator of the extent of consumption smoothing in an economy. When people are able to maintain a smooth path of consumption optimal to them, irrespective of fluctuations in income, relative consumption volatility is less than one. However, empirical evidence on emerging economy business cycles shows that relative consumption volatility exceeds one, and has increased after financial sector reform in most of these countries (Kim et al. 2003, Alp et al. 2012, Ghate et al. 2013) (Table 1). In this background, we address the question: under what conditions can financial development lead to a rise in relative consumption volatility? (Bhattacharya and Patnaik 2015)

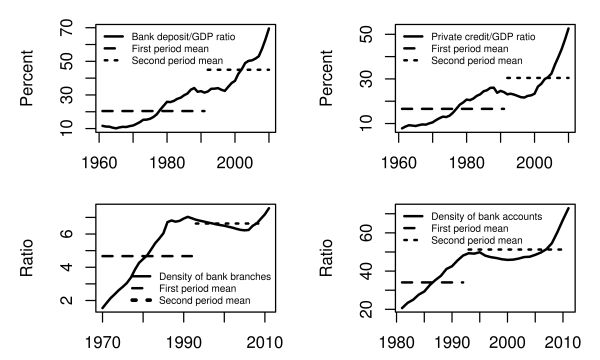

Table 1. Relative consumption volatility: Selected emerging economies

Note: This table shows the reform date and relative consumption volatility in the pre- and

Source: Datastream, Authors' calculations.

The theory

Theoretical literature on finance and macroeconomic volatility explores how financial integration and financial development affect income and consumption volatility through the channel of firms and households (Bernanke and Gertler 1989, Greewald and Stiglitz 1993, Aghion et al. 2004, Iyigun and Owen 2004, Buch et al. 2005, Leblebicioglu 2009, Aghion et al. 2010). The early theoretical literature predicts that financial development reduces macroeconomic fluctuations (Bernanke and Gertler 1989, Greewald and Stiglitz 1993). More recent literature suggests that the nature of relationship between financial development and macroeconomic volatility can be non-linear (Aghion et al. 2004) and may depend on several factors, such as the composition of short- and long-term investments (Aghion et al. 2010) and dynamics of inequality in the economy (Iyigun and Owen 2004).

Access to finance, permanent income shock and consumption volatility

Not all consumers in emerging economies have access to finance (Honohan 2006). Households without financial services cannot smooth consumption, and their consumption volatility is as high as income volatility; relative consumption volatility is at most one. Increased access to finance for constrained households through financial development (Figure 1) should help in consumption

Emerging economies, however, feature permanent income shocks, that is, shocks to

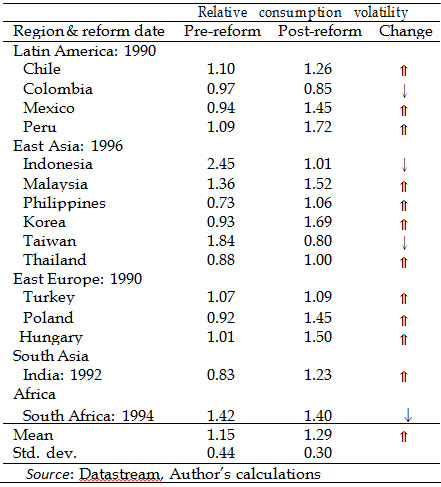

Figure 1. Financial development

Notes: (i) This figure shows a commonly used indicator for financial development, namely the total bank deposits to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio, for a set of emerging economies. The figure shows, on average, a rise in the indicator over time. The rising trend in the ratio is also visible for individual countries. (ii) The set of emerging economies consists of Chile, Columbia, Mexico, Peru, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Poland, Hungary, India and South Africa.

Source: International Financial Statistics, International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Financial inclusion, permanent income shock and consumption volatility

We analyse the joint impact of easing financial constraints and permanent income shock on consumption volatility, in a dynamic general equilibrium model with two type agents. Low financial inclusion implies that all households in the economy do not have access to finance. These financially constrained households can neither save nor

The increase in current period consumption resulting from shocks to income perceived as permanent is higher than the increase in current period

Evidence for India

We test the model's key prediction by calibrating it for India, an emerging economy which has witnessed financial sector reform; rise in consumption fluctuations (both absolute and relative) following reforms (Ang 2011, Ghate et al. 2013); and large fluctuations in its trend growth due to drastic policy regime shifts. We calibrate the model to Indian data for pre- and post-reform years. We capture financial inclusion through a reduction of the fraction of constrained households in the post-reform period.

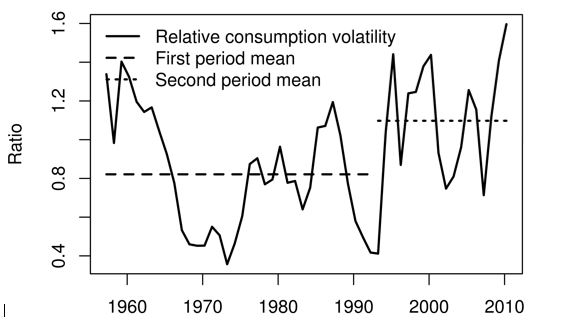

Figure 2 depicts the trend in relative consumption volatility for India, estimated from the volatility of cyclical components of real GDP (at factor cost) and private consumption expenditure. The mean (average) of relative consumption volatility shows an increase in the post-reform period.

Figure 2. Trend in relative consumption volatility

Note: This figure shows five-year rolling relative consumption volatility in India during 1956-2009.

Source: National Accounts Statistics, India; Authors' estimates.

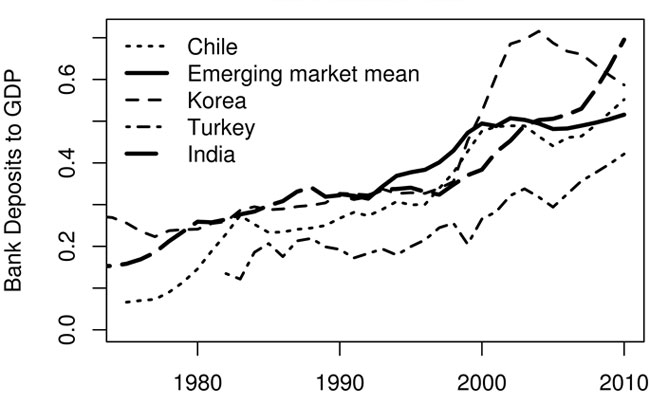

India has witnessed development in its domestic financial sector during the post-reform

Figure 3. Financial development in India

Notes: (i) This figure shows the behaviour of some financial development indicators in India. The upper two panels depict bank deposit to GDP ratio and the private credit to GDP ratio. The left lower panel shows the number of bank branches in 100,000 population. The right lower panel shows

Sources: International Financial Statistics, IMF; World Development Indicators, World Bank and Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

There has been a sharp increase in access to finance after reforms. The ratio of bank accounts in the total population was merely 20% in 1980; it was above 70% by 2010, with a period of decline in the trend during 1990-2005.

Decomposition of the Solow residual1 for India into permanent and transitory components shows that shocks to trend growth are a major source of fluctuations in the Indian business cycle. The Kalman filtered estimate2 of transitory shock is 0.32%, as opposed to the magnitude of the estimated shock to the growth rate of the permanent component of 1.59%.

We simulate the model economy using the values for the underlying parameters pertaining to India. We source some of the parameter values from existing literature, while we estimate the rest

Effect of financial inclusion on relative consumption volatility

Table 2. Business cycle volatilities from the simulated model

Note: This table presents absolute and relative business cycle volatilities from the simulated model for the pre- and post-reform period. The absolute and relative standard deviation numbers are in percentage (%).

The results from the simulated model support its key prediction. With other factors unchanged, we observe that a reduction in the fraction of financially-constrained households in the post-reform period results in a rise in relative consumption volatility, replicating the pattern observed in the data (Table 2). We also observe an increase in absolute consumption volatility in the

We observe that the model, augmented to an open economy framework where financial transactions by unconstrained households take place through an internationally traded; one-period; risk-free bond, also supports the main prediction of rising relative consumption volatility with financial inclusion when calibrated to Indian data.

A feature, not a bug

Emerging economies have witnessed an increase in consumption volatility relative to output volatility, after financial development. This behaviour appears puzzling since traditional models and evidence from advanced economies suggest that consumption should become smoother with increased access to financial services.

Unconstrained households (with access to finance) respond to permanent income shocks (which are often caused by economic reforms) by increasing current consumption by more than the rise in current income, by borrowing against future income or reducing current savings. Consumption fluctuates more than income in emerging economies, resulting in relative consumption volatility greater than one.

Greater financial inclusion resulting from financial sector reform allows more households to access financial services. More households become unconstrained and can respond to the income shock that they perceive as permanent. As a result, financial development in an emerging economy leads to an increase in relative consumption volatility.

A rise in relative consumption volatility in an emerging economy is a consequence of economic and financial reform. It is thus a feature, not a bug. Future research needs to understand the path from this rise in relative consumption volatility in an emerging economy to lower consumption volatility as seen in advanced economies.

Notes:

- Solow residual is the standard measure of total factor productivity growth. It is that part of output growth that cannot be accounted for by the growth of the primary factors of production (capital and labour).

- Kalman filtering is an algorithm that uses a series of measurements observed over time, containing statistical noise and other inaccuracies, and produces estimates of unknown variables that tend to be more precise than those based on a single measurement alone.

Further Reading

- Aghion, Philippe, George- Marios Angeletos, Abhijit Banerjee and Kalina Manova (2010), “Volatility and growth: Credit constraints and the composition of investment”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 57 (3): 246–265.

- Aghion, Philippe, Philippe Bacchetta and Abhijit Banerjee (2004), “Financial development and the instability of open economies”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 51: 1077–1106.

- Aguiar, Mark and Gita Gopinath (2007), “Emerging market business cycles: The cycle is the trend”, Journal of Political Economy, 115 (1): 69-102.

- Alp, H, Y Baskaya, M Kilinc and C Yuksel (2012), ‘Stylized facts for business cycles in Turkey, Working Paper No 12/02, Research and Monetary Policy Department, Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey.

- Ang, James (2011), “Finance and consumption volatility: Evidence from India”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 30: 947–964.

- Aslund, A (2012), ‘Lessons from reforms in central and eastern Europe in the wake of the global financial crisis', Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper No. 12-7.

- Bernanke, Ben and Mark Gertler (1989), “Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations”, American Economic Review, 79(1): 14–31.

- Bhattacharya, Rudrani and Ila Patnaik (2015), “Financial inclusion, productivity shocks, and consumption volatility in emerging economies”, World Bank Economic Review, Pages 1-31,

doi : 10.1093/wber/lhv029. - Buch, Claudia, Joerg Doepke and Christian Pierdzioch (2005), “Financial openness and business cycle volatility”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 24: 744–765.

- Ghate, Chetan, Rohini Pandey and Ila Patnaik (2013), “Has India Emerged? Business Cycle Facts from a Transitioning Economy”, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 24: 157–172.

- Greenwald, Bruce and Joseph E. Stiglitz (1993), “Financial market imperfections and business cycles”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108 (1): 77–114.

- Honohan, P (2006), ‘Household financial assets in the process of development', World Bank Policy Research, Working Paper No. 3965.

- Iyigun, Murat and Ann Owen (2004), “Income inequality, financial development, and macroeconomic fluctuations”, The Economic Journal, 114 (495): 352–376.

- Kim, Sunghyun, M Ayhan Kose and Michael G Plummer (2003) “Dynamics of business cycles in Asia: differences and similarities”, Review of Development Economics, 7 (3): 462–477.

- Leblebicioglu, Asli (2009), “Financial integration credit market imperfection and consumption smoothing”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 33: 377–393.

- Naoussi, Francis Claude and Fabien Tripier (2013), “Trend shocks and economic development”, Journal of Development Economics, 103: 29–42.

- Rodrik, Dani (2008), “Understanding South Africa's economic puzzles”, Economics of Transition, 16(4); 769–797.

- Singh, A, A Belaisch, C Collyns, PD Masi, R Krieger, G Meredith and R Rennhack (2005), ‘Stabilization and reform in Latin America: A macroeconomic perspective on the experience since the early 1990s', Occasional Paper No. 238, International Monetary Fund.

16 December, 2015

16 December, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.