There is ample anecdotal evidence on political parties bribing voters with cash or consumption goods prior to elections, in India and other developing countries. However, there is an expected lack of hard evidence on the extent and form of vote-buying. Using data from Indian states, this column analyses consumption patterns of households around elections, and finds a spike for some items just before elections.

In countries where norms regarding election financing are ambiguous, and/or legal limits on corporate donations to political parties are small, the issue of mobilising sufficient funds by contesting parties assumes a certain degree of complexity. This is not to say that considerable funds are not generated; there exists ample anecdotal evidence of voters being bribed with cash or actual consumption goods prior to elections. The Indian media regularly carries news about cash seized during various elections, ranging from Rs. 19.5 million in Assam to Rs. 155 million in Tamil Nadu during the 2014 Lok Sabha1 election.

However, not surprisingly there is a clear lack of hard evidence of the extent and form of vote-buying, largely because neither political parties nor voters have any incentives for revealing any details regarding the cash (and ‘kind’) that changes hands. The lack of transparency in this matter is especially acute in developing countries like India where political parties lack any recourse to public funds for contesting elections. Furthermore, this creates incentives for opportunistic business agents to both influence election outcomes and enjoy perks by forming clientelistic relations with politicians and political parties. It is plausible that some of the money used in these contexts arises from donations, which forms the ‘black money’ stocks in the country. Given that the legal limits are low enough to be binding in most cases, opportunistic donors find it profitable to use their black money holdings to back their favoured party/parties2.

There are several country-specific studies (example, Brazil (Gingerich 2010), Britain (Eggers and Hainmueller 2009) and Russia (Akhmedov and Zhuravskaya 2004)), which look at the connection between election financing and corruption. In the case of India, Kapur and Vaishnav (2013) show that ?rms in the construction sector face short-term liquidity crunches during elections, reflected in lower level of activity in building and construction. However, this lull disappears post-elections, suggesting that the finances in this sector may be used for vote-buying.

Analysing consumption patterns of voters around elections

In recent research (Mitra, Mitra and Mukherji 2016), we attempt to garner evidence of vote-buying by using a different methodology. Our approach to the whole issue is novel: we look at the consumption patterns of households and examine how they vary before and after elections. Clearly, we intend to capture the actual change (presumably, rise) in expenditure by the voters as a result of any cash transfer they might receive from the campaigning parties. We use data from all the major Indian states. Hence, our analysis is certainly representative of India, and quite possibly reflects the existing conditions in many other developing nations.

There are two main challenges that arise in such an analysis. First, on what do people spend the windfall gain? After all, households consume a variety of items on a daily basis. Moreover, this is not just any cash transfer: it is a form of bribe; a fact that is evident to both the donor and recipient. So which items of household consumption are more receptive to such a cash injection? The second challenge is more on a technical level. How can one be sure that the comparison of consumption expenditure in the ‘before’ and ‘after’ phases actually reflects the role of elections? What if other factors systematically change, which confounds the causal link from elections to change in expenditures?

We take adequate cognisance of both of these issues in our analysis. We pay particular attention to items highlighted in the anecdotal evidence, namely, liquor, meat, and items of clothing like saris. We also look at expenditure items such as health and education, which are considered stable and not reliant upon unexpected cash injections. These items conceptually are a benchmark against which one can evaluate the movement in expenditure of the ‘usual suspects’ (like liquor and clothes). We let our intuition guide the choice of the set of items that we focus on.

Our two key sources of data are the National Sample Survey (NSS) rounds on household consumption expenditure, conducted during 2004–2011, and state assembly elections data pertaining to that period. Each NSS consumption module contains detailed information on the surveyed households’ monthly consumption expenditure on over 300 different commodities. Additionally, each of these survey rounds takes a year to complete and covers all states. For every surveyed household we have information on the date of the survey. Combining this with the data on state assembly elections3, we are able to ascertain whether a household is reporting on consumption close to elections. Given that in a particular year only some states have elections , we have a sample with different groups: there are households that reported their consumption just a few days before they voted and those that did so many days before or after voting. In fact, we construct ‘time windows’ of different lengths prior to election dates to see how the consumption pattern changes. We compare these groups with the ‘reference group’, which comprises households in neighbouring (non-election) states that were surveyed on similar dates. In this manner, we are able to tackle the second challenge since the timing of surveys is independent of that of state assembly elections.

Evidence on vote-buying

Our prior here is that if there is no vote-buying, then the timing of election should not matter for patterns in consumption of any commodities. Our first significant observation is that household consumption is indeed impacted by elections! Moreover, the effects are quite substantial. This, by itself, is proof that vote-buying is a rampant practice in India.

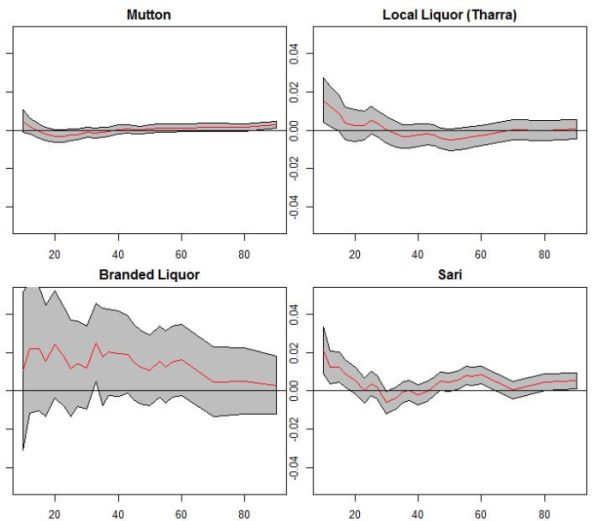

The question is - on what do households spend the windfall gain? We find that households tend to spend more on a range of staples, and, to an extent, on ‘intoxicants’. While our results are strongest for saris and other clothing, we see the pattern in several other items. Figure 1 below shows the spike in consumption for some items just before elections. Notice the contrast between local liquor and branded liquor suggesting that the former responds to election periods while the latter does not.

Figure 1. Consumption patterns around elections

Notes: Zero time denotes the election date, where the x-axis gives the number of days prior to the election and the y-axis records the expenditure. The red line reflects the predicted expenditure (based on our regression estimate) and the grey band around it represents the 5% confidence interval.

Notes: Zero time denotes the election date, where the x-axis gives the number of days prior to the election and the y-axis records the expenditure. The red line reflects the predicted expenditure (based on our regression estimate) and the grey band around it represents the 5% confidence interval. The larger picture

At a very basic level, our study engages with the question of how households behave when they receive money, aside from their regular earnings. Of course, one has to account for the kind of money injections: temporary or permanent, legal versus illegal, and so on. In general, there is limited understanding of the choice of expenditure items when households are exposed to unexpected income; our work sheds some light on this.

Is it possible to link norms of election? financing to dynastic politics? We believe that the answer is in the affirmative (this is the subject of our ongoing research). Election? financing, campaign-spending regulations, black money, and the corrupt use of public funds are all inter-connected. Patronage through political dynasties and social networks may well play a prominent role in shaping voting patterns and ultimately policy.

Notes:

- Lok Sabha is the lower house of Indian parliament. See: http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/political-parties-wooing-electorates-with-liquor-cash-household-benefits-and-drugs/printarticle/51858290.cms

- There is no reason to assume that private donors restrict themselves to just a single party. In order to smooth out risk, they often donate to multiple competing parties.

- The Election Commission announces state assembly elections months in advance. Typically, 3-4 states go to elections in a year. Also, all districts in a state go to elections on the same date, but this may not be the case for large states.

- There is a literature on consumption smoothing and informal risk-sharing behaviour, which while illuminating on many aspects does not deal with which types of consumption respond to such types of income shocks.

Further Reading

- Akhmedov, Akhmed and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya (2004), “Opportunistic Political Cycles: Test in a Young Democracy Setting”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4):1301-1338. Available here.

- Eggers, Andrew C and Jens Hainmueller (2009), “MPs for Sale? Returns to Office in Postwar British Politics”, American Political Science Review, 103(4):513-533. Available here.

- Gingerich, D (2010), ‘Dividing the Dirty Dollar: The Allocation and Impact of Illicit Campaign Funds in a Gubernatorial Contest in Brazil’, Working Paper, University of Virginia. Available here.

- Kapur, D and M Vaishnav (2013), ‘Quid Pro Quo: Builders, Politicians, and Election Finance in India’, Working Paper, Center for Global Development.

- Mironov, M and E Zhuravskaya (2013), ‘Corruption in Procurement and Shadow Campaign Financing: Evidence from Russia’, Working Paper, Paris School of Economics. Available here.

- Mitra, A, S Mitra and A Mukherji (2016), ‘Cash for Votes: Evidence from India’, mimeo.

20 April, 2017

20 April, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.