A key, stated objective of the recent denotification of high-denomination currency notes was to eliminate black money arising from tax evasion, and to expand the tax net. In this article, Sangram Gaikwad and Kailash Gaikwad, officers of the Indian Revenue Service, outline the challenges faced by the tax administration in dealing with rampant evasion in direct taxation, and what can be done to address the issue.

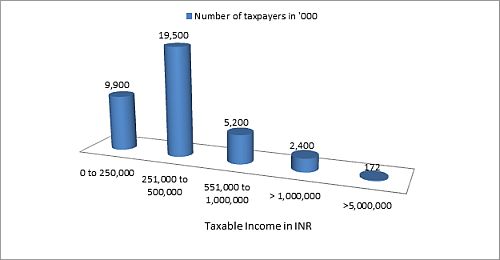

In his Budget speech on 1 February 2017, the Union Finance Minister stated that we are largely a tax non-compliant society. His statement signals a serious deficit in tax compliance, reflected in the relevant numbers. At 5.55%, we have one of the lowest direct taxes-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratios (2014-15). Figure 1 below shows the spread of taxpayers against their taxable income.

Out of 37.1 million individuals who filed tax returns in 2015-16, 9.9 million show income below the exemption limit of Rs. 250,000 per year, 19.5 million show income between Rs. 250,000 to Rs. 500,000, 5.2 million show income between Rs. 500,000 to Rs. 1 million, and only 2.4 million people show income above Rs. 1 million. Of the 7.6 million individual assesses who declare income above Rs. 500,000, 5.6 million are in the salaried class1.

These figures are absurdly low for a country of more than 1.25 billion and aren’t commensurate with the general economic activity seen in our society.

Direct tax non-compliance and response of the taxman

Though the modes and benefits of non-compliance may vary across different categories of taxpayers, compliance is very low across all of them if measured on a single parameter of payment of net tax to the government. The salaried class may possibly be an exception here. The challenges of enhancing compliance differ for different categories of taxpayers. However, it is possible to broadly group these taxpayers into three categories on the basis of income range and the challenges typical to them in tax administration.

The first category is of persons who are completely beyond the tax net in spite of having taxable income. Most of these are individuals and firms involved in businesses or professions in the informal sector, and do not have large scale-dealing with the organised sector. Owing to their large number and extent of non-compliance, this group has the potential to adversely affect the macroeconomic parameters of the economy, including loss of tax revenue. These are fence-sitters keeping their turnovers of trading or manufacturing just below the threshold limits for registering with indirect-tax authorities such as VAT (value-added tax) and excise. The threshold limit for registration with VAT is Rs. 1 million. Businesses having turnovers up to Rs. 2 to 3 million manage to show their accounted turnover below the threshold limit. They are part of a large crowd unwilling to be seen on the registers of the tax authorities. It is very easy to prove their tax evasion if the tax authorities visit their premises and examine the transaction history. However, the cost of such monitoring processes is quite high and the tax authorities have limited and scarce resources. The taxation law and policy has sought to bring them under the tax net through presumptive taxation schemes2 but its impact has been below the expectation. Since nearly all transactions of such enterprises take place in cash at the customer end, it becomes very easy for them to fashion their accounted transactions as per their needs. These non-corporate entities, as also small or shell companies, are often used for round-tripping3, and hence, capital-building through fake means (Shome et al. 2014; pp. 297). These persons/enterprises come under watch of authorities only when they undertake high-value transactions like purchase of property, large cash deposits, undisclosed tax deducted at source, credit card payments, etc. With the help of ICT (information and communications technologies) and data mining techniques, the Income Tax Department has recently devised Non-filers Monitoring System (NMS) to catch these entities. However, due to limited resources, heavy reliance on cost-intensive scrutiny assessments, and huge volume of such cases, the follow up of these cases becomes a herculean task.

Second category is of taxpayers in the middle- and upper-income range who don’t pay their tax to their potential, and are in substantial numbers. In case of some of the businesses in this category including jewellers, traders, metal processors and manufacturers, and real estate concerns, this becomes a habitual practice over a period of time. The most common ways of tax evasion are to suppress the receipts or inflate the expenses, resulting in lower taxable income. Transactions with fence-sitting enterprises, which are out of the tax net, may come handy for making such manipulations. Abuse of various provisions of tax incentives/exemptions, including those for agricultural income, is also another widely used practice. The process of auditing of select cases by the tax Authorities is one of the important deterrents against the practice of tax evasion. In India, it is carried out primarily by way of desk-auditing, which is called scrutiny assessment. Compared to international practice of having various kinds of auditing mechanisms based on risk assessment information, the Indian practice of desk-audit as the sole mechanism is primitive and needs to be changed (Shome at al. 2014; pp. 292).

Measured through the lens of efficiency in boosting revenue collections and deterrence, the process of scrutiny assessment does not fare well. All the enquiry/investigation processes initiated in the Indian scenario have to culminate into a scrutiny assessment carried out by a tax officer without any assistance from experts. The officers are over-burdened with work and face many systemic challenges in doing high-quality scrutiny assessments. Due to the presence of a highly cash-intensive, widespread informal sector; a plethora of tax incentives; about 60% of population dependent on agriculture, which is exempt from direct taxation; lack of coordination among various enforcement authorities including tax authorities at the state and central levels; and ingenious ways employed by people for manipulating transactions - the job of tax officers becomes much more difficult. A simple test to check the efficacy and quality of assessment is to examine the percentage of cases in which the assessments are challenged in appeal by the taxpayers and/or the Tax Department. The data for 2011 shows that appeals were filed in 25% of the cases in which scrutiny assessments were carried out in India. The corresponding figures were 0.48% for Australia, 0.62% for Canada, 0.04% for South Africa, and 3% for the US (Singh 2016; pp. 435). Improper appreciation of facts, lack of field enquiry, not gathering third-party information or corroborative evidence also make tax assessments weak, resulting in litigation and non-recovery of taxes, besides increasing the compliance cost to taxpayers and the administrative cost of the Tax Department (Singh 2016; pp. 554). This process of scrutiny assessments consumes most of the resources and energy of the Department, while contributing little to augmentation of collections. The process has become akin to the tax authorities chasing their own tail.

The third category is of large taxpayers (mostly corporate) using sophisticated and evolved methods of tax avoidance and evasion. These are in the form of complex arrangements of transactions through cobweb of various entities; shifting of profits to low-rate jurisdictions including tax heavens; abuse of tax incentive schemes; manipulations in the books of accounts, etc. There are certain industries such as real estate, film, fashion, mining, construction, gems and jewellery, which are highly prone to manipulations and have deep-rooted legacies and practices of deviant behaviour. Large numbers of hawala4 operators and accommodation entry providers5, who are ready to offer low-cost services for manipulations of transactions, are also part of the ecosystem that has developed a high level of resistance to anti-evasion measures. The tax evasion in these cases is often linked to other methods and areas, which serve as beds of parallel economy.

As per international practice, auditing of large taxpayers is carried out by a team of specialists with the help of multidisciplinary experts. Resources for auditing such cases are allocated on a priority basis. However, no such special treatment is given to the cases of large taxpayers in India in terms of processes or resources. It is important for the tax administration to develop specialisation and domain knowledge of various sectors of the economy to carry out effective audits (Shome et al. 2014; pp. 291). The auditing of large taxpayers is also required to be conducted jointly by the direct and indirect tax authorities in order to achieve effective compliance at reasonable costs (Shome et al. 2014; pp. 294).

Way forward

Income Tax Department is at the forefront, among government agencies, as far as adoption of ICT based practices is concerned. However, a lot more is required to be done in order to re-engineer the existing processes comprehensively. The internal processes of reporting, review, judicial filings, enforcement and departmental communication, which are still carried out on paper should be completely shifted to already available e-modes. The existing process of auditing, hinged solely on scrutiny assessment, needs to be diversified and organically linked with the processes of risk profiling and data analytics. The Tax Administration Reforms Commission has provided valuable insights and action points in this regard in its reports.

Views expressed in the article are personal.

Notes:

- Paragraph 141 of Budget speech of the Union Finance Minister, delivered on 1 February2017.

- As per sections 44AA of the Income-tax Act, 1961, a person engaged in business is required to maintain regular books of account under certain circumstances. To give relief to small taxpayers from this tedious work, the Income-tax Act has framed the presumptive taxation scheme under sections 44AD and 44AE. A person adopting the presumptive taxation scheme can declare income at a prescribed rate and, in turn, is relieved from the tedious job of maintenance of books of account.

- Round-tripping refers to circular movement of capital. In the context of black money, capital leaves the country through various channels such as inflated invoices, payments to shell companies overseas, the hawala route, and so on. After cooling its heels overseas for a while, this money returns in a freshly laundered form; thus completing a round trip.

- Hawala is a traditional system of transferring money whereby the money is paid to an agent who then instructs an associate in the relevant country or area to pay the final recipient.

- Accommodation entry providers are persons providing for fictitious transactions of purchases, sales, loans, shares, etc. by using shell entities.

Further Reading

- Shome, P, YG Parande, S Kalia, MK Zutshi, SSN Moorthy, S Mahalingam, MR Diwakar (2014), ‘Tax Administration Reform in India: Spirit, Purpose and Empowerment’, First Report of the Tax Administration Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

- Singh, RR (2016), Challenges of Indian Tax Administration, Lexis Nexis.

01 March, 2017

01 March, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.