With 99.3% of banned currency returning to the banks, it is clear that demonetisation’s primary objective of nullifying ‘black money’ was not achieved. In this post, Dr Renu Kohli contends that it is also difficult to conclude – as some others have done – that demonetisation either raised tax buoyancy more than other measures, or lowered cash intensity in the economy.

With the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) publishing its final figure that 99.3% of cancelled cash returned to the banks, the government’s primary target of demonetisation to nullify black money has obviously come a cropper. What is interesting is the remaining 0.7% of the de-legalised notes need not necessarily be black – a large chunk of this could be small amounts remaining stuck with millions of NRIs (non-resident Indians), Nepal and Bhutan residents1, and other foreign nationals. Thus, almost 100% of the cancelled currency turned out to be white!

No one knows for sure how much black money was hoarded in cash: the government reportedly told the Supreme Court this could be about Rs. 4–5 trillion, while some economists believed it could be Rs. 2–3 trillion. But even by the most conservative estimate of Rs.1.5 trillion, a spectacularly large amount of currency changed colour, much to the discomfort of the government. Hoarders turned out to be smarter, acted fast to exploit systemic loopholes, were supported by an army of middlemen, backed by lawyers and accountants, and possibly collusive banks that opened their back-doors to them! The government certainly did not think through multiple routes that hoarders could exploit, failed to plug these gaps fast enough, and perhaps lacked imagination to outmanoeuvre opponents when a game-theoretic situation2 emerged...

Failing to stop the black money in hoarders’ pockets, the government changed tack by labelling large deposits in bank accounts as “suspicious”, subject to scrutiny and heavy penalty through a new Taxation Laws (Second Amendment) Bill, 2016, and also introduced a voluntary disclosure scheme Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, 2016 (PMGKY) midway. There were expectations these two instruments could attract nearly Rs. 1–1.5 trillion to the exchequer. But the outcome turned out even worse for all it collected was a paltry Rs. 49 billion. Surely the hoarders covered their tracks well, had the confidence to come out clean! To simply let it pass by terming these as “ingenious act of black-money holders” does not pass muster.

Who are these depositors? We know the tax department has been trailing 1.8 million such depositors for over a year now, but not sure if this will yield any significant dividend. But the government surely used these trails to spin around – that demonetisation enabled a large increase in direct tax compliance and revenue buoyancy. This appeared pure desperation to find an escape route; any tax research expert would tell you how difficult it is to isolate factors leading to higher compliance. And in this instance, there could be many: apart from trend factors such as better tax administration, electronic trailing of expenses, reducing tax rate to 5% in the lower bracket, the government introduced more lethal instruments such as linking bank accounts and PAN3 (Permanent Account Number) card to Aadhaar4 and also rolled out GST (goods and services tax). Even without demonetisation, the last two undoubtedly had huge potential for more transparent business transactions and income accrued thereby. In fact, Financial Express research estimates that GST-linked contribution to direct taxes’ compliance could be much larger than that of demonetisation.

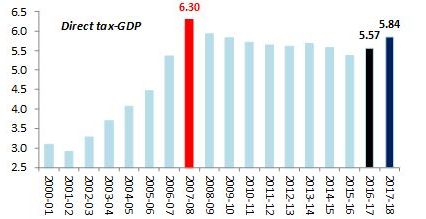

But the moot question is did higher tax compliance increase tax revenues sharply? The Figure 1 below clearly illustrates the 5.84% direct tax-GDP ratio in 2017-18 was way below the 6.3% peak achieved in 2007-08. Nor is it significantly higher than the preceding 10-year average of 5.72%. Merely adding lakhs of new tax returnees does not serve any purpose if they do not contribute significantly to tax collections.

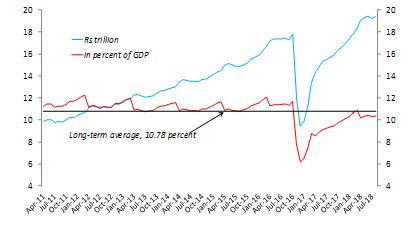

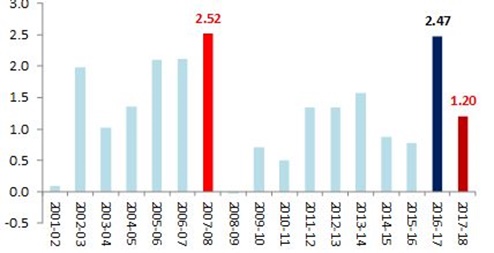

Some would argue that personal income tax buoyancy (Figure 2) at 2.47 in 2016-17 was far higher than the 0.9 average in the previous eight years, but what would explain the quite sharp fall to 1.2 in 2017-18 when compliance should have improved even further. Corporate tax buoyancy (Figure 3 below) in contrast improved in 2017-18 as GST unfolded. Notably, data for the first quarter (April-June, 2018) reported by the Controller General of Accounts (CGA) show that personal income tax buoyancy further declined to 0.93, while that of corporate income tax had turned negative.

It’s amply clear that tax buoyancy is too volatile an indicator to make a case. The fact that historically the economy witnessed much better tax buoyancy - between 2002-03 and 2007-08 – even without any structural interventions like demonetisation, GST, and Aadhaar, conforms to apprehensions of desperation in stretching meek data points to claim success!

Figure 1. Demonetisation raised tax-GDP ratio? Mind the peaks and the slope!

Source: FY18 – Controller General of Accounts (CGA); FY16-FY17 – Union Budget 2018-19; up to FY15 – Income Tax Department.

Source: FY18 – Controller General of Accounts (CGA); FY16-FY17 – Union Budget 2018-19; up to FY15 – Income Tax Department. Figure 2. Personal income tax buoyancy: No extra bounce

Figure 3. Corporate tax buoyancy: No gains here either

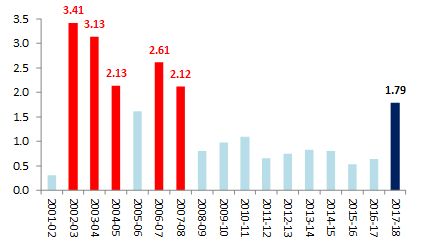

Figure 4. Currency in circulation

Note: Nominal GDP growth for 2018-19 assumed 11.5% as per Union Budget 2018-19.

Note: Nominal GDP growth for 2018-19 assumed 11.5% as per Union Budget 2018-19.Source: RBI & author’s calculations.

Beyond the critical failure to tame black money the government had moved the goalpost to another objective to achieve less cash-dependent economy, encouraging citizens to move to more digital transactions. Although laudable, the objective to bring in transparency and savings from printing currency depended upon behavioural changes in consumers and more formalisation of activities. Though government never advocated any particular level of currency-to-GDP ratio, it hoped the shock of demonetisation would leave some imprint upon consumers’ minds to store less cash; some economists even suggested the one-time increase in deposits after demonetisation would stay in the banking system for much longer, thus reducing interest rates and thereby supporting investment and growth.

But despite the government’s best efforts to promote digital transaction and advancing the GST rollout, cash returned to the public at a much faster pace than anyone anticipated. Figure 4 shows long-term trend in currency-GDP as well as absolute stocks. After reaching 10.9% this March, the currency-GDP ratio has been an average 48 basis points lower than the historical 10.78 to which the ratio reverts seasonally. Here too there is an attempt to spin estimates to claim some degree of success as much as a labouring to substantiate more formalisation and job creation! One needs to be careful if the rise in currency holdings of household financial savings are any indication of behavioural change – currency demand could accelerate as cash-dependent segments such as the informal sector recover from damages caused by demonetisation, housing sales come out of the doldrums, and demand for gold and jewellery returns. And we have not even flagged the other two objectives espoused by the government to demonetise – reducing counterfeit notes, and choking terrorist funding!

Demonetisation was an extraordinary experiment in economic policymaking that raised social, political and ethical questions. But from a purely macroeconomic perspective, the interplay of demonetisation in relation to its targets and objectives is fascinating if only because of its novelty. For such an experiment, where a single policy instrument is deployed as a one-shot, unanticipated shock to attain multiple targets is quite unique to macroeconomic policy manuals, the more so because of its possible structural implications. Having spectacularly failed to meet any of its multiple objectives, it is now left to history to document if spins that its advocates offer as an afterthought has any substance for future governments to take note of.

This article first appeared in Financial Express: https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/defend-demonetisation-but-at-least-sound-credible/1302893/

Notes:

- Indian currency is widely used in Nepal and Bhutan, with the latter giving it status of legal tender.

- Game theory comprises strategy games or interactions between two or more players within a set of rules in competitive or conflict situations. It is used in economics to model behaviours, and to determine the most likely outcomes of situations.

- Permanent Account Number (PAN) is a 10-digit alphanumeric identifier, issued by the Income Tax Department. Each assessee (individual, firm, or company) is issued a unique PAN.

- Aadhaaror Unique Identification number (UID) is a 12-digit individual identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) on behalf of the Government of India. It captures the biometric identity – 10 fingerprints, iris and photograph – of every resident, and is meant to serve as a proof of identity and address anywhere in India.

12 October, 2018

12 October, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.