The National Health Assurance Mission – India’s first move towards Universal Health Coverage – is expected to be launched soon. In this context, this column analyses the extent, distribution and quality of current public spending on healthcare. It suggests that the planning for a national programme for health coverage should take into account issues of fragmentation, inequity and inefficiency in the public healthcare system.

The new government at the centre is preparing to launch the flagship National Health Assurance Mission (NHAM), which is India’s first move towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC)1. The programme plans to provide access to all healthcare services (primary, secondary and tertiary) including drugs and diagnostics, to the entire population. The aim is to make 50 essential drugs (in generic forms), a package of diagnostics, and about 30 AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy) drugs, available to all citizens at government hospitals and health centres across the country, along with a comprehensive package of preventive and positive health information2. NHAM would also have a strong insurance component, which would be free for those below the poverty line (BPL) and at a low premium for the rest of the population (Press Release, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW)).3,4

Although details are awaited, the initiative immediately brings to mind the question of resource needs for such a large programme. Estimating the resource requirements for NHAM requires a comprehensive understanding of the amount, distribution and quality of current government spending on the health sector as a whole, and on health coverage in particular5. Existing evidence on this is relatively sparse.

Analysing current public spending on health

In light of these questions, we estimate aggregate public spending on health and its distribution across levels of government (centre/ state/ local). We also specifically estimate public spending on health coverage by consolidating and analysing financial information on government-sponsored schemes for healthcare services targeted at different sections of the population. Finally, we look at the variation in per beneficiary cost across selected health schemes (Chowdhury and Gupta 2014a). The objectives are twofold: to understand the level and composition of public spending on health and health coverage, and the equity implications of this spending. The results are potentially relevant to the proposed NHAM of the government.

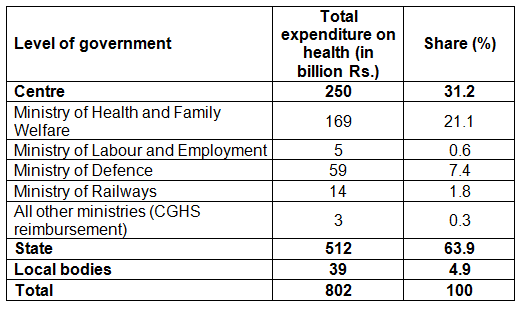

Our analysis indicates that the total spend on health by the government in 2010-11 was Rs. 80,155 crores (US$ 17.6 bn approx.)6, a mere 1.03% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at current prices (Table 1a). The bulk of this was spent by state governments (64%), with the centre spending about 31%7,8. MoHFW contributed just 21% to the total expenditure; the rest was from the Ministry of Defence (7.4%), Ministry of Railways (1.8%) and the Ministry of Labour and Employment (0.6%). Clearly, the MOHFW is not a major player as far as public spending on health is concerned.

Table 1a. Public expenditure on health, 2010-11

While much of the health sector spending of the government goes towards the subsidised public health system, it has not ensured universal coverage primarily on account of relatively low utilisation of the public health system due to access and quality issues. Continued low access and the associated lack of financial protection have prompted the government (including state governments) to come up with scheme-based programmes for health coverage. To align our analysis with this more distinct definition of health coverage, we focus specifically on public spending on scheme-based health coverage for specific segments of the population. This includes healthcare services of the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Railways, Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS)9, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY)10, Employees State Insurance Scheme (ESIS), medical reimbursement by state government departments, state government health schemes etc. Overall, around 19% of total government spending for the health sector goes specifically into spending for health coverage via these schemes. The centre-state division in this expenditure is now 70-30. Thus, while the share of states in overall spending on the health sector is relatively more, the centre’s share is greater in terms of spending on healthcare services coverage. The major contribution comes from the Ministry of Defence (41%). The other significant share is that of the CGHS (15%).

Table 1b. Public expenditure on health coverage, 2010-11

| Level of government/ Scheme | Expenditure on health coverage (in billion Rs.) | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Centre | 10.0 | 69.6 |

| Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | 21 | 14.7 |

| Central Government Health Scheme | 21 | 14.7 |

| Ministry of Labour and Employment | 5 | 3.6 |

| Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana | 5 | 3.6 |

| Ministry of Defence | 59 | 41.3 |

| Ministry of Railways | 14 | 10.0 |

| State | 44 | 30.4 |

| Department of Health and Family Welfare | 19 | 13.1 |

| Employees State Insurance Scheme | 4 | 2.9 |

| Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana | 2 | 1.2 |

| Other departments (medical reimbursement/ allowance) | 19 | 13.2 |

| Local Governments | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 143 | Public spending on health coverage: Are we raising the right questions? |

Comparing costs across healthcare schemes

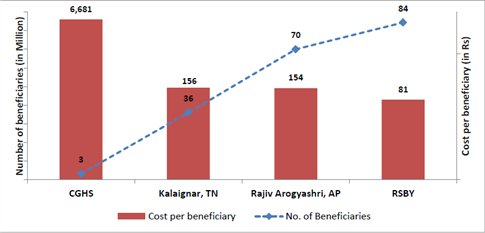

Next, we estimate the cost per beneficiary of selected schemes - CGHS, RSBY, Kalaignar (Tamil Nadu) and Rajiv Arogyashri (Andhra Pradesh)11(Figure 1). The schemes are quite different in terms of coverage (size of population, sections of population covered), level of care or the “benefit package”, and geographical reach.12

Figure 1.Costs per beneficiary of selected healthcare schemes

Source: Budgets and annual reports of Ministry/ departments of health and family welfare of the central and state Governments

Source: Budgets and annual reports of Ministry/ departments of health and family welfare of the central and state Governments

We find that the CGHS is the most expensive health coverage programme in the country (Rs. 6,681 per beneficiary per year).If we compare self-contained schemes (those that have their own infrastructure and network of service providers), the costs per beneficiary of Defence and Railways are much higher than the ESIS (Rs.5,938, Rs. 2,254 and Rs. 552 respectively). While Defence may be treated as an exception due to the special needs of the target population, the difference in the per beneficiary costs of ESIS and Railways is hard to explain unless accounted for by differences in the profile of the target population and their healthcare needs (ESIS covers blue-collared factory workers, while Railways cover all rail employees). The state-run schemes and the RSBY, which cover the BPL segment, are relatively much cheaper with costs below Rs. 150 per beneficiary. It can be argued that these schemes are only for hospitalisation and thus the costs are lower than for those that cover Out-Patient Department (OPD) services as well. However, whether such inclusion would increase costs per beneficiary is an empirical question; in any case, the difference in costs is too high to be accounted by this factor alone.

Total spending on central-government employees (through CGHS) is more than eight times the spending on the BPL segment (through RSBY). Also, while CGHS has just 3.2million beneficiaries, RSBY covers 84 million individuals. Although lower per beneficiary costs of larger schemes partly reflects economies of scale and possibilities of resource pooling, it also indicates the iniquitous incidence of public expenditure. The low-cost schemes are targeted at the BPL populations while the high-cost schemes cover the non-BPL segments (see Figure 1). The exclusively centrally-run schemes cater to the relatively better-off populations and cover all levels of care - primary, secondary and tertiary, including high-end specialised care and surgeries. The other schemes have relatively narrow coverage in terms of services. Thus, besides introducing inequity in ‘who is covered’, the expensive schemes also bring in inequity in ‘what is covered’.

Designing a national programme for health coverage: Way forward

Clearly, the government needs to address both the quantum and quality of spending on health. So far, the MOHFW has not been a major player in the health sector; therefore any move towards UHC needs to be implemented with the active and willing participation of the state governments, who are the major spenders. However, states have been unable to expand their expenditures to any significant extent, primarily on account of limited sources of revenue and low implementation capacity. Moreover, substantial inequalities exist in revenue and expenditure capabilities across states (Chowdhury and Gupta 2014b). The recent increase in centrally-designed and centrally-sponsored schemes like the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) requiring matching contributions from the state governments have imposed a burden of committed expenditures on the already resource-starved states. In spite of this, a UHC blueprint cannot and should not be, drawn up solely by the central government or the MoHFW.

Most of the discussion on raising resources for UHC revolves around new and innovative ways of raising additional revenues through sin taxes (such as on cigarettes) or public-private partnerships (PPPs) etc. Very little discussion has taken place in India on the possibility of augmenting existing resources by pooling and consolidating the current system of health coverage. Our analysis raises two important concerns that need to be addressed while planning for a national programme of health coverage: equity and efficiency. Both are intricately related to the question of the aggregate resource envelope required for launching an all-India programme. Our analysis indicates that the current system of health coverage by government is fragmented, costly and iniquitous. Also, the subsidies in healthcare (for example, those given to beneficiaries of various schemes like CGHS, Railways and Defence) are not being targeted well and similar schemes are running at different costs. Besides being more resource-efficient, pooling also has the potential of promoting equity, if the resources are more evenly spread across the population. Hence, unless issues of targeting, pooling and consolidation are worked out in advance, proper estimation of total resource requirements of the new system seems difficult.

The decision to consolidate the currently fragmented schemes is not a politically easy one because it requires dismantling a systemthat has been delivering subsidised health coverage for a considerable period and at considerable costs, to a small section of the population. Ethics demand that we openly acknowledge the absence of efficiency and equity in the current healthcare system, examine how those that are currently outside the system can be brought in so that the entire population can get more or less the same level of public subsidy and health coverage.

Notes:

- According to the World Health Organization, UHC embodies three related objectives: equity in access to health services, quality of health services that is good enough to improve the health of those receiving services, and financial-risk protection - ensuring that the cost of using care does not put people at risk of financial hardship.

- This refers to information that gives positive reinforcement about health issues; example, importance of getting regular blood sugar tests done, benefits of physical exercise etc.

- http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=110121

- http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=110556

- By health coverage, we essentially mean healthcare schemes run by various government departments plus reimbursements of medical expenses of employees of both central and state governments. Expenditure on health coverage is a part of aggregate expenditure on the health sector, which also includes other expenses like those on salaries, infrastructure, maintenance etc. that are outside of these specific schemes.

- The premise of our analysis is that such an estimate does not exist for India. The National Health Accounts that was last published in 2004-05 did a projection for the subsequent years, according to which the figure for the year 2008-09 was Rs. 58,681 crore (US$ 9.8 bn approx.).

- According to the Constitution of India, health is a state subject. Hence, all state-specific needs and priorities in the health sector are addressed by respective state governments. The key role of the central government is in improving the health system of the country primarily through the National Health Mission (NHM). The NHM has subsumed most of the vertical disease control programmes earlier run by the central government. The centre also spends on medical education and research.

- The remaining 5% is spent by local governments, public sector undertakings and other quasi-government institutions.

- Under CGHS, medical reimbursement is provided to employees of all central government ministries.

- The RSBY or the National Health Insurance Scheme covers hospitalisation expenses in empanelled public or private health facilities, up to a ceiling of Rs. 30,000, for BPL families and other unorganised sector workers. About 75% of the scheme is funded by the central government and the rest by state governments.

- The Chief Ministers Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (Kalaignar) of the state of Tamil Nadu provides insurance coverage of Rs. 100,000 to families with annual income of Rs.72,000 or less and members (and families) of labour welfare boards, for in-patient expenses in empanelled public and private hospitals. The Rajiv Arogyashri Health Insurance Scheme of Andhra Pradesh provides coverage of Rs. 150,000 per BPL family per year with additional buffer of Rs. 50,000 for identified hospitalisation procedures in empanelled public and private hospitals.

- CGHS, ESIS and schemes offered by the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Railways are self-contained; they have their own infrastructure and network of service providers. Such schemes provide primary, secondary and tertiary care as well as out-patient and in-patient services. On the other hand, schemes like the RSBY and some of the state-level health schemes like Rajiv Arogyasri only include in-patient treatments (hospitalisation) up to a certain financial limit.

Further Reading

- Gupta, I and S Chowdhury (2014a), “Public financing for health coverage in India: Who spends, who benefits and at what cost”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 49, Issue No. 35, 30 August 2014.

- Gupta, I and S Chowdhury (2014b), ‘Scaling up Health Expenditure for Universal Health Coverage: Prospects and Challenges’, India Infrastructure Report 2013-14, IDFC Foundation, Orient BlackSwan, New Delhi.

- Press Information Bureau (2014), ‘Dr Harsh Vardhan showcases government’s early achievements in health’, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 29 September 2014.

- Press Information Bureau (2014), ‘Health Ministry Parliamentary Consultative Committee lauds Minister’s apolitical stand’, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 15 October 2014.

13 February, 2015

13 February, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.