The average years of education per Indian citizen have significantly increased since independence. This column analyses whether the increase in education has led to higher material wellbeing overall. It finds that the increase in education has produced disappointingly small increases in household consumption. The reason appears to be that very few men and hardly any women are in salary employment where the value of extra education is high.

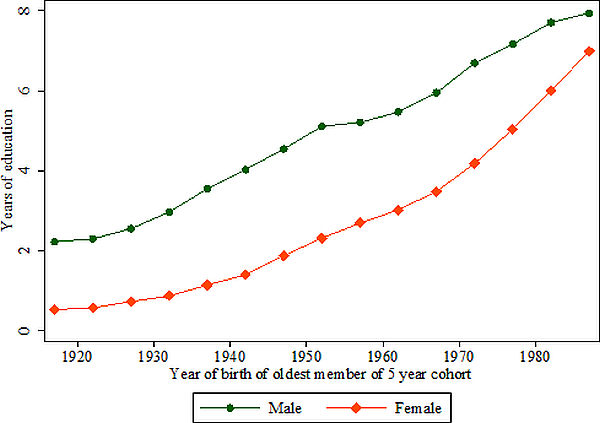

Since independence, the average years of education per Indian citizen has increased tremendously (Figure 1). The prominent party symbols during the recent elections serve as a potent reminder that at independence most Indians could not read: these party symbols allowed even the illiterate to find their candidate on the ballot1. The expansion of education among so large a population has been a great accomplishment.

Figure 1. Average years of education per Indian citizen, 1917-1987

Notes: Figure 1 shows the average educational attainment of the group (cohort) of men and women born in a particular year (depicted on the horizontal axis). Groups are averaged over five years to always include a year ending in zero or five since many Indians (particularly those with little education) cannot accurately report their year of birth Groups born after 1987 may not have fully finished their education and so are not included. Source: National Sample Surveys (NSS) and Fulford (2014).

Notes: Figure 1 shows the average educational attainment of the group (cohort) of men and women born in a particular year (depicted on the horizontal axis). Groups are averaged over five years to always include a year ending in zero or five since many Indians (particularly those with little education) cannot accurately report their year of birth Groups born after 1987 may not have fully finished their education and so are not included. Source: National Sample Surveys (NSS) and Fulford (2014).

Yet all is not well with Indian education. While most children now go to school for at least a few years, there is much room for improvement in the quality of the education that they receive. Spot visits to schools in many states show that teacher absenteeism is very high. Even when they are present, the quality and quantity of teaching is often poor2. Paradoxically, the rapid growth in Indian education has made it harder to deliver good education: how are parents, who may not be able to read themselves, to tell whether their children are learning?

Has the increase in education led to greater material wellbeing?

Delivering high-quality education is something that all nations struggle with. A deeper question in India is whether the rise in education will bring with it the benefits that many hope it will. In a recent paper, I examine just how much the increases in education have increased material wellbeing using multiple years from the NSS (Fulford 2014).

Quantifying what economists call the returns to education — the additional monetary value that comes from an increase in education — is not an easy task. Looking around, it is clear that those with more education typically earn more. How much of the increase in earnings is because of the extra education, and how much comes from other factors is not obvious. For example, the more ambitious, talented, or better-connected people, who would do well anyway, may find school a useful way to demonstrate their talent, even if it does not make them more productive. Yet they must spend years in school rather than working to signal their talent. And if employers use education as a way to choose people for jobs, more education for one person may mean that another does not get his or her dream job. Hence, the effects of an increase in education can spill over onto others in the job market or the marriage market. In a competitive world, it is not always clear that an increase in education for one person enhances the overall welfare of the society.

One way to understand these issues is to compare age groups across states and time. This accounts for the possibility that those with more education may be more hard working or come from families with better connections. In any given year the 25-30 year olds are no more capable on average than the 30-35 year olds when they were 25-30. But the 25-30 year olds typically have more education. Comparing groups also helps account for the problem that if one person in a group gets an additional year of education and takes a job from someone else in the group, then the group as a whole does not earn any more. Similarly, if education helps on the marriage market or is associated with marrying a higher earning husband or wife, looking at age groups accounts for the negative spillovers onto others competing for a limited pool of grooms or brides.

An additional obstacle to understanding the value of education in India is that very few people work for an easily quantifiable wage. In 2008, only about 40% of working-age men and 14% of working-age women regularly earned a wage (NSS). Part of the reason to attain a higher level of education may be that it helps secure a steady — and hopefully high — salary. So it would be a mistake to leave out those who are not working for a wage, since we might miss the returns to education that come from the switch from self-employment to working for a wage.

This distinction turns out to be particularly important for women in India. The largest increases in education have been among women. Yet women still work primarily inside the home. Hence, understanding whether this increase in education has brought any material gains for women must involve examining something other than wages.

One way around this problem is to focus on household consumption. We cannot ask whether a woman with a higher level of education earns more than a woman with less education if both work inside the home since both receive zero wages, although they may contribute to their families’ welfare in other ways. Instead, we can ask whether better educated women live in households that consume more.

Comparing the household consumption per person of age groups across states and over time, I find that an extra year of education for men means they live in households with 3% higher consumption per person. But better-educated women do not live in households that spend more on average3. It seems that we can explain very little of the variation in consumption across age groups and states with education.

Explaining low returns to education in India

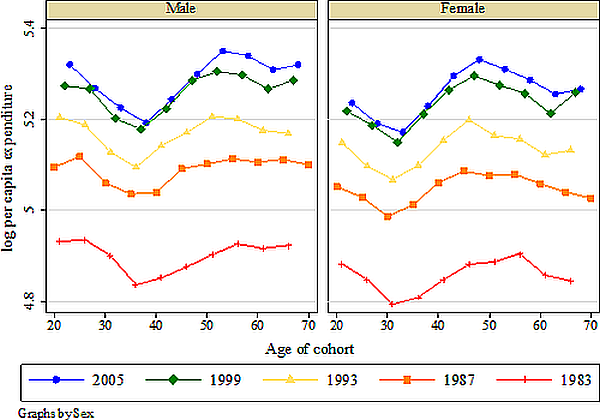

These low returns are surprising, but it is easy to illustrate where they come from. Figure 2 shows the average household consumption per person for different ages in the major rounds of the NSS (adjusted for inflation). A comparison of the bottom line (1983) with the top line (2005) shows the tremendous growth in India in terms of consumption. On average, Indians are consuming much more. Figure 1 showed that younger Indians have much more education. Yet consumption has grown for all ages approximately equally, suggesting that very little of this growth can be attributed directly to the increases in education.

Figure 2. Consumption by age, 1983-2005

Source: NSS and Fulford (2014).

Source: NSS and Fulford (2014).

Why are the returns so low? It does not seem that quality of education by itself is the answer. The returns to education are only slightly higher in states with better education systems as measured by a standardised test in the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) in 2005. This implies that bringing every state’s schools up to the quality of the best will not necessarily increase the returns to education much, although it certainly will not hurt.

Instead, the answer appears to be in the ability of the Indian economy to use a more educated workforce. When there are rapid technological innovations that can be widely used, as happened during the Green Revolution in Punjab, the returns to education can be high (Foster and Rosenzweig 1996). But most Indians still work in various forms of self-employment or home production where the value of extra education is less obvious. Looking only at those who work for wages, better educated groups of males earn substantially more than less educated groups. Most of the returns to education seem to be coming from those who have a regular salary, not from those in the casual labour market.

So a large part of the reason that the overall return to education is so low for men is that the one area where there are high returns to education — salary employment — absorbs only 20% of working-age men. Similarly, because so few women are employed for a regular salary, we see even lower returns to education for women. Put a different way, the reason education does not have high returns is because so few Indians work in areas where education is likely to be valuable.

There is reason to be optimistic, however. Even if the returns to education have been low in the past, that does not mean they have to always be low. India now has an immense pool of educated men and women whose education is not being used very productively. One of the greatest challenges to Indian growth, but also one of its greatest opportunities, will be whether India can employ the growing education of its entire people, particularly its women.

Notes:

- For a description of the monumental work of the first general elections in a large and illiterate country see pp. 143-145 in Guha, R (2007), India After Gandhi, Harper Collins, New York, USA. Most of the increases in education in India since independence have been at the primary or middle level, although secondary schooling has spread as well (Fulford 2014).

- See, for example, the work of the Public Report on Basic Education in 1999 and a more recent update (De et al. 2011).

- In Fulford (2014) much of the work is to establish that this result is not driven by: (i) the way consumption is measured, (ii) age-group definitions, or (iii) measurement error.

Further Reading

- De, A, R Khera, M Samson and AK Shiva Kumar (2011), ‘PROBE Revisted: A Report on Elementary Education in India’, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, India.

- Foster, AD and MR Rosenzweig (1996), “Technical change and human-capital returns and investments: Evidence from the green revolution”, The American Economic Review, 86(4):pp. 931–953.

- Fulford, S (2014), “Returns to Education in India”, World Development, 59: pp. 434–450.

- Guha, R (2007), India After Gandhi, Harper Collins, New York, USA.

- PROBE Team (1999), ‘Public Report on Basic Education in India’, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, India.

18 September, 2014

18 September, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.