Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have significance in a labour-abundant country like India, and various policies are in place to promote the sector. Analysing MSME data from various sources, this column shows that the structure of manufacturing MSMEs has changed significantly in the last decade: the share of capital-intensive industries in output has increased; labour productivity remains very low with possible replacement of labour with capital.

In a labour-abundant country like India, the importance of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) cannot be overemphasised. Under the ‘Make in India’ campaign launched in 2014, which aims to promote Indian manufacturing, a slew of benefits have been announced for MSMEs in terms of reimbursement of technology acquisition costs, rollover relief from capital gains tax, and measures to facilitate the flow of formal finance to the sector − in addition to sector-specific initiatives.

India stands apart when compared to many developed and developing economies due to the reservation policy support provided to small-scale industries (SSI). Despite all these attempts to give a boost to the MSME sector, data and research show that the productivity of small firms in Indian manufacturing is abysmally low relative to larger firms. This has created a conspicuous ‘missing middle’ in the size structure of firms, which deters employment generation and dynamism in Indian manufacturing (Mazumdar and Sarkar 2009). The ineffectiveness of the industrial policy designed for the MSME sector warrants special attention of policymakers, and a systematic, in-depth analysis of the profile of the sector to understand the post-policy impact. Such attempt has been minimal so far due to the non-availability of time-series1 data for the sector from one single source. The quinquennial2 NSS (National Sample Survey), which provides data on various characteristics of unincorporated manufacturing entities, comes with considerable time lag. The same is true of the All-India Census of MSMEs, which was last conducted in 2006-07.

Based on analysis of MSME data from various sources for the latest years available in each source, I find that the structure of manufacturing MSMEs has changed significantly in the last decade. Not only has the share of capital-intensive industries within the output composition of manufacturing MSMEs increased, labour productivity remains very low with possible replacement of labour with capital within manufacturing MSMEs. This is often not given due importance in policy formulation.

Structural change within manufacturing MSMEs

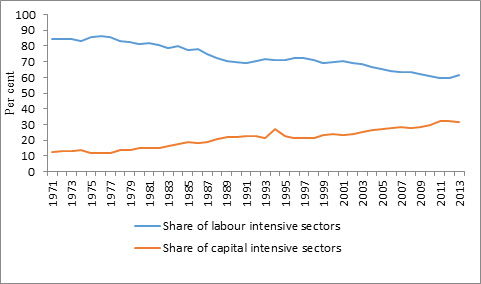

As per the data provided by the 4th Census of MSMEs, almost 86% of the manufacturing MSMEs operating in the country are unregistered. The output data for unregistered manufacturing from the National Account Statistics (NAS) reveals a notable trend in terms of change in output composition of the unregistered manufacturing MSMEs in recent years: the share of sectors with above-average capital intensity in the total output of unregistered manufacturing has steadily risen from 23% in 1991 to close to 33% in 2013, with a commensurate fall in the share of more labour-intensive sectors (Figure 1). The same trend emerges if we look at the relative share of sectors as per the use-based classification: the share of capital goods has steadily increased from 12% in 1971 to 25% in 2013.

Figure 1. Output composition of unregistered manufacturing MSMEs

Capital intensity and capital productivity of manufacturing MSMEs

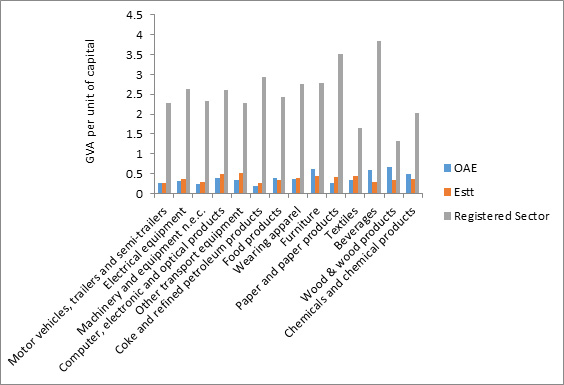

On comparing the capital intensity (capital-to-labour ratio) of registered manufacturing from ASI (Annual Survey of Industries) data with that of unregistered manufacturing3 obtained from NSS, it is seen that in recent years, the registered segment is almost 12 times more capital intensive than unregistered “establishments” (the bigger firms within unregistered segment with at least one hired labour), and the capital intensity of unregistered “establishments” is twice that of own account enterprises (OAEs)4. Clearly, capital intensity and firm size exhibit a positive relation which reinstates the importance of the MSME sector in job creation. But what is also important is that capital productivity of small unregistered firms is significantly low in Indian manufacturing, especially in motor vehicles, electrical equipment, machinery, and food products (Figure 2). Moreover, I find a declining trend in capital productivity5 coupled with rising capital intensity in most of these sectors (Table 1). This indicates that probably, the rise in capital intensity has not been technology-induced productivity-augmenting; rather it replaces labour in most of these sectors. In fact, both capital and labour productivity was found to be very low in manufacturing MSMEs as compared to bigger firms. The labour productivity index for OAEs was found to be close to zero when compared with the registered sector (=100) for the year 2011.

Figure 2. Capital productivity in Indian manufacturing, 2011

Table 1.Trend in capital intensity and capital productivity

| Industries | Growth in capital intensity (%, 2006-2011) | Growth in capital productivity (%, 2006-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacture of food products and beverages | 74.95 | -10.40 |

| Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products | 223.39 | -6.80 |

| Manufacture of leather and related products | 237.42 | -6.70 |

| Manufacture of wearing apparel | 133.56 | -3.80 |

| Manufacture of textiles | 75.20 | -6.60 |

| Manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products | 269.60 | -15.40 |

| Manufacture of wood and products of wood and cork, except furniture; straw, etc. | 170.69 | -8.40 |

| Manufacture of tobacco products | 355.54 | -10.20 |

Source: Author’s calculations based on NSS data.

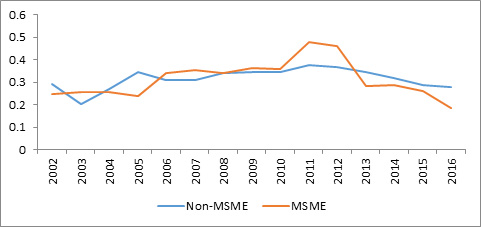

Total factor productivity

I calculate total factor productivity (TFP) for a sample of MSME firms obtained from the CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt Ltd) prowess database, for the period 2002-2016.The overall trend in TFP suggests that though the TFP of MSMEs was close to non-MSMEs within registered manufacturing, from 2010 onwards there was a significant drop in TFP of MSMEs (Figure 3). In addition, I find that within unregistered manufacturing, TFP growth was negative in the case of motor vehicles, machinery, rubber and plastic products, basic metal, textile and wearing apparel, during 2006-2011.

Figure 3. Trend in TFP

Policy implications

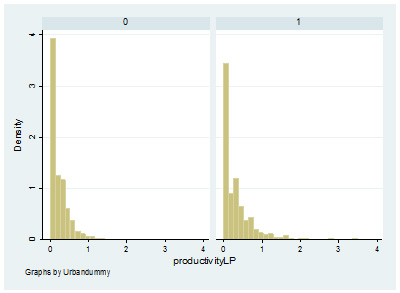

The special policy support provided to small firms has its economic rationale embedded in the facts that (i) these firms are more labour intensive;( ii) in a labour-abundant country, these firms use the scarce resources in a more productive manner; (iii) without intervention, small firms face higher factor costs which results in a sub-optimal size of the SSI sector in the economy (Little 1987, Hussain 1997). The policy support to the MSME sector in India can be classified into (i) promotional versus protective; (ii) one-shot versus continuous; and (iii) discretionary versus non-discretionary (Tendulkar and Bhavani 1997). It is worth mentioning here that the earlier reservation policy for the SSI sector has been criticised for distorting the size structure of firms within Indian manufacturing, and deterring the growth of small firms by providing perverse incentive to these firms to remain perpetually small (Mohan 2002, Nataraj et al. 2017). As a result, such protectionist policies were gradually replaced by promotional measures after liberalisation. In recent years, the policy for MSMEs in India has largely been promotional and discretionary in nature. However, successful implementation of any discretionary policy depends crucially on careful identification of target firms, which is very difficult due to the information asymmetry present between various government agencies and the beneficiaries. Possibly as a result of this, MSMEs which are located in major urban centres are found to have significantly better productivity as compared with MSMEs located in remote areas (Figure 4). Ensuring outreach of various policies towards its intended beneficiaries would require a concerted effort of various government agencies responsible for designing such policies. In this context, the ‘Udyog Aadhaar’6 initiative is a welcome move.

Figure 4. Distribution of firm-level productivity of manufacturing (registered) MSMEs

Note: 1 indicates urban location

Further, the analysis brings out the fact that despite being labour intensive in nature, the labour productivity of manufacturing MSMEs is significantly low compared to large firms. TFP, which is an indicator of technical progress, also exhibits a sharply declining trend for manufacturing MSMEs in recent years. In addition, not only has there been a structural shift in the output composition of the MSME sector towards more capital-intensive industries, there has also been a possible replacement of labour with capital in major labour-intensive industries within MSMEs. All these facts suggest that instead of solely emphasising on the labour-intensive production process of MSMEs, policies should be designed such that the sector achieves its efficient scale of production and dynamism. Though the need for factor market intervention (Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, 2015) to ease supply-side constraints for small firms cannot be denied, it also becomes important to recognise the structural change in the sector in favour of capital intensity, which could be due to increased participation in the international trade. The manufacturing MSMEs’ abysmal low labour productivity increases the effective labour cost, as a result of which there is labour displacement in major labour-intensive sectors within the manufacturing MSMEs. Hence, at this juncture, a policy aimed at creating jobs within manufacturing needs to focus on improving the labour productivity of the MSME sector. Undoubtedly, India’s poor performance in creating a broad-based vocational education system remains a major hindrance in achieving this objective.

Notes

- Time series refers to a sequence of values for a variable over time at consistent time intervals.

- Quinquennial means occurring or being done every five years.

- Almost all firms in unregistered manufacturing are very small in size and come under the MSME category as per the official definition of MSME in India.

- Own account enterprises are family-owned firms which do not hire outside workers. These are typically smaller relative to “establishments”.

- Here, capital productivity is gross value added (GVA) per unit of fixed assets for the year 2011.

- Ministry of MSME has prepared a one-page registration form that constitutes a self-declaration format under which an MSME can self-certify its existence, bank account details, etc., based on which it can be issued online, a unique identifier – Udyog Aadhaar Number. Enterprises can use the Udyog Aadhaar Number to access other services. The registration process is free of cost, paperless, and instant.

Further Reading

- Hussain, A (1997), ‘Report of the Expert Committee on Small Enterprises’, 27 January 1997.

- Levinsohn, James and Amil Petrin (2003), “Estimating Production Functions Using Inputs to Control for Unobservables”, The Review of Economic Studies, 70(2):317-341.Available here.

- Little, IMD (1987), “Small Manufacturing Enterprises in Developing Countries”, The World Bank Economic Review, 1(2):203-235.

- Manjón, Miguel, Juan A Máñez, María E Rochina-Barrachina and Juan A Sanchis-Llopis (2013), “Reconsidering learning by exporting”, Review of World Economics, 149(1):5-22.

- Martin, Leslie A, Shanthi Nataraj and Ann E Harrison (2017), “In with the big, out with the small: Removing small-scale reservations in India”, The American Economic Review, 107(2):354-386.

- Mazumdar, Dipak and Sandip Sarkar (2009), “The employment problem in India and the phenomenon of the missing middle”, The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 52(1):43-55. Available here.

- Mohan, R (2002), ‘Small-scale industrial policy in India: A critical evaluation’, in Krueger, AO (ed.), Economic Policy Reforms and the Indian Economy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Ministry of Micro, Small &Medium Enterprises (2015), ‘Report of the Committee set up to examine the financial architecture of the MSME sector, Government of India, February 2015.

- Olley, G Steven and Ariel Pakes (1996), “The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry”, Econometrica, 64(6):1263-1297. Available here.

- Tendulkar, Suresh D and TA Bhavani (1997), “Policy on Modern Small Scale Industries: A Case of Government Failure”, Indian Economic Review, 32(1):39-64.

12 December, 2017

12 December, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.