In countries across the world, de-industrialisation is taking place earlier in the development process. This column analyses how India fares in this regard. It finds that for most Indian states, the share of manufacturing in GDP peaked in the 90s, at levels far lower than comparable Asian countries, and began declining thereafter. Reversing this process is not going to be easy.

Can India be a manufacturing powerhouse? Three developments make that question salient today. Looming ahead is the demographic bulge, which will disgorge a million young people every month into the economy in search of employment opportunities. Rising labour costs in China create opportunities for low-skilled countries such as India as replacement destinations for investment that is leaving China. And a new government assuming power this month offers the prospect of refashioning India in the image of Gujarat, which has been one of the few manufacturing successes.

High-productivity and dynamic manufacturing sector

Manufacturing is an important sector into which resources should flow for two reasons: the level of productivity and its dynamism. If this were to happen, the economy would become more productive through a reallocation of resources from less productive to more productive sectors and also because productive sectors would become more so over time.

In India, the sector with these characteristics is registered (formal) manufacturing. According to our calculations, the level of labour productivity (measured as value added divided by employment) in 2010 was about 4.2 times greater in formal manufacturing than in the rest of the economy. Second, between 1999 and 2010, productivity in this sector grew at an annual average rate of 5.3% compared with 4.3% for the rest of the economy. Note that these benefits only pertain to formal manufacturing because informal manufacturing is a low-productivity and non-dynamic sector - compared to not just formal manufacturing but large parts of the economy.

Thus, the desirability of India becoming the next China or the next Gujarat is not in doubt. The real issue, and the open question, relates to feasibility. And there is a sobering fact here: India has been de-industrialising, big time.

Premature deindustrialisation across the world

In a piece that one of us wrote recently, we noted the fact, first pointed out by Dani Rodrik, that ‘early’ or ‘premature’ de-industrialisation is happening worldwide. At any given stage of development, countries are on average specialising less in manufacturing. Furthermore, the point in time at which the share of industry peaks (alternatively, the point at which de-industrialisation begins) is happening earlier in the development process.

For example, in 1988, for the world as a whole, the peak share of manufacturing in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 30.5% on average and attained at a per capita GDP level of $21,700. By 2010, the peak share of manufacturing was 21% (a drop of nearly a third) and attained at a level of $12,200 (a drop of nearly 45%).

How do Indian states compare?

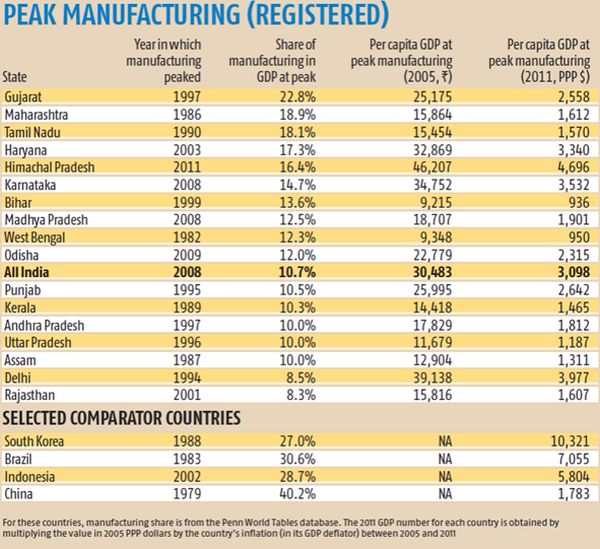

What has been the equivalent development within the Indian states? Table 1 below provides data, showing the year in which the share of registered manufacturing in GDP peaked, the peak level of manufacturing, and the per capita GDP associated with peak manufacturing levels.

Figure 1. Peak levels of (registered) manufacturing

A few points are striking. Gujarat has been the only state in which registered manufacturing as a share of GDP surpassed 20% and came anywhere close to levels achieved by the major manufacturing successes in East Asia. Even in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, manufacturing at its peak accounted for only about 18-19% of state GDP.

Second, in nearly all states (with the possible exception of Himachal Pradesh), manufacturing is now declining and has been doing so for a long time. The peak share of manufacturing in many states was reached in the 1990s (Gujarat and Tamil Nadu) or even in the 1980s (Maharashtra).

Third, and this is perhaps the most sobering of facts, manufacturing has even been declining in the poorer states: states that never effectively industrialised (West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan) have started de-industrialising.

Some comparisons are illuminating. Take India´s largest state, Uttar Pradesh. It reached its peak share of manufacturing, of 10% of GDP, in 1996 at a per capita state domestic product of about $1,200 (measured in 2011 purchasing power parity dollars). Indonesia attained a manufacturing peak share of 29% and at a per capita GDP of $5,800. Brazil attained its peak share of 31% at a per capita GDP of $7,100. So, Uttar Pradesh´s maximum level of industrialisation was about one-third that in Brazil and Indonesia; and the decline began at 15-20% of the income levels of these countries.

Need to change policies to make Indian manufacturing attractive to investment

These findings serve to emphasise that if India is to become a manufacturing powerhouse, it has to reverse a process that has been entrenched for several years in several states. It is not that patterns of specialisation cannot be changed. But that reversal will require a lot of hard work, so that a critical mass of policies is changed to create an environment that is conducive to making high-productivity manufacturing attractive to investment, domestic and foreign.

Time, or rather the weight of history, is not on the side of Indian manufacturing.

A version of this column has appeared in Business Standard.

Further Reading

- Subramanian, A, (2014), ‘Premature De-industrialization’, Center for Global Development Blog, 22 April 2014.

- Rodrik, Dani (2013), ‘On premature deindustrialization’, Dani Rodrik’s weblog, 11 October 2013.

26 May, 2014

26 May, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.