While much has been said about the poor working and living conditions of short-term migrants, relatively little is known of the impact of short-term migration on child welfare. This column finds that although short-term migration does not lead to child labour, children of migrants have poorer educational outcomes.

Compared to other developing countries, permanent migration to cities in India is rare. However, many researchers and policymakers have noticed a large group of poor, often tribal, short-term migrant workers. Much has been written of temporary, circular and seasonal migrants, particularly with regard to their poor working and living conditions, lack of access to public services and programmes, and exploitation by employers and labour contractors (Breman 1996, Mosse et al. 2002, Banerjee and Duflo 2007, Haberfeld 1999, Rogaly 1998). However, relatively little has been written about their children. So, what are the implications of short-term migration for child welfare?

I was a part of a team that undertook a survey in a tribal region on the borders of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat in 2010 to investigate the linkages between short-term migration, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)1 and rural livelihoods (Coffey et al. 2013). The survey included several questions about the children of short-term migrants, and produced some surprising findings on the impact of short-term migration on children’s welfare (see Coffey, 2013).

About the survey, the families and the children

The survey covered about 700 households in 70 villages in five districts. More than half of the households self-identified as scheduled tribe (ST). Moreover, the region is extremely poor - 93% of households have a dirt floor; 71.3% do not have electricity; 60% of women who are 45 years and older have had a child who was born alive and later died; and adult women in the region have completed less than a year of schooling, on average.

Households in the survey had three main sources of income - from agriculture, migrant work and MNREGA. Agriculture is predominantly rain fed, so the main growing season is the monsoon. Migration is an important livelihood strategy, particularly in the summer season, when agriculture is unproductive. Despite high rates of short-term migration, there is very little permanent migration from this region.

Both adult and child migration rates are quite high. 80% of households sent at least one adult migrant in the year before the survey. Among 20-30 year old men, over 80% migrated in the year before the survey, and the corresponding figure for women was over 60%. Of the 1,980 children age 0-13 in the households that were interviewed, almost 30% migrated with adult family members in the year before the survey. Migration is most common for young children - half of the infants migrated with their mothers in the year before the survey. Older, school-aged children migrate less, but still in large numbers - about a fifth of the 10 year olds surveyed migrated in the year before the survey.

A surprising finding about child migration and child labour

What do children who migrate do when they are at the worksites? A lot has been written about child labour at migrant worksites (Breman 1996, Mosse et al. 2002, Gupta, 2003), but surprisingly, this survey found very little child labour among migrant children and that too, only among older children. These findings are based on adults’ reports of what children do when they migrate. Multiple responses were allowed for the question. It was found that 20.5% of children did domestic work (for their own households) on their last trip; 5.7% worked for pay; 3.3% helped with the work of adults, but were unpaid; 2.1% went to school; and 79.5% “did nothing”. Paid or unpaid work (other than household tasks) was done only by children 10 years of age and older - 20% of 10 year olds, 22% of 11 year olds, 50% of 12 year olds and 58% of 13 year olds were reported to have worked.

Are these low figures for child labour plausible? I think they are. First of all, if children were productive at worksites, it is likely that more of them would have migrated; 18% of children in the 10-13 years age group migrated in the year before the survey. Second, most parents work at construction sites for which they are paid a pre-set daily wage, rather than a piece rate. Employers may not want to risk hiring an unproductive worker, or getting in trouble with the law, as most construction work is done outdoors. It is common to see children at work sites, but uncommon to see them working. Third, it is unlikely that parents failed to report child labour out of fear of disapproval or other negative consequences. In the survey, respondents were assured confidentiality, and they did report other things, for example child marriage, which are technically illegal, but not often enforced.

Migrant children miss out on school

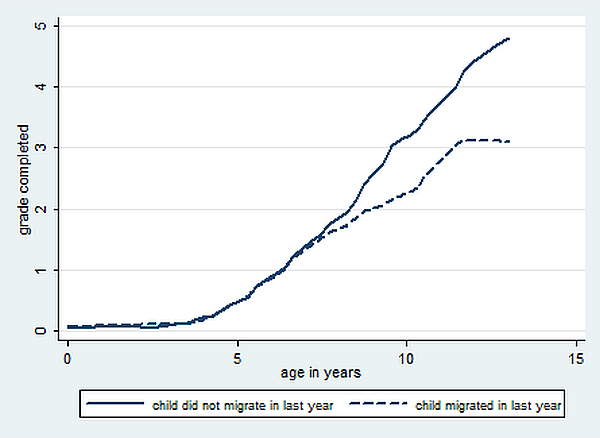

In this population of migrants, fears that child labour was a major problem at migrant worksites were, fortunately, not realised. However, the study uncovered another problem with child migration - its relationship with schooling. The figure below shows the average grade completed for children who did and did not migrate in the year prior to the survey, by age. It shows that 13 year old children who migrated in the year before the survey had completed about two years less schooling, on average, than those who did not migrate.

Figure 1. Child migration and schooling

Children who migrate are disadvantaged for other educational outcomes as well. For example, they are seven percentage points less likely to have ever been to school and nine percentage points less likely to have been to school the day before the survey.

The disadvantage in grade completion among migrant children is not due merely to the fact that fewer migrant children have ever been to school. Indeed, it is present even among those who are enrolled in school. However, this gap is also there when I restrict the analysis to the group of children who have the highest chances of migration — children whose mothers have migrated. It is also the case that between two children of the same mother, one who migrated and one who did not, the one who migrated would, on average, have completed fewer years of schooling for her age.

This analysis suggests that the migration of children leads to poor educational outcomes, for which there are several plausible mechanisms. First, migration may lead students to forget what they have learned in school, or prevent them from developing relationships with teachers and classmates that help them progress through school. Second, it may break the habit of going to school. It is also possible that it the causation works the other way around, and that some children migrate because they are doing poorly in school.

Give mothers a reason to stay back

Even without being certain about whether migration causes poor school outcomes, or vice versa, it may make sense to implement policies that encourage children to be left behind in villages. If migration causes poor school outcomes, then children left behind will get more schooling. Even if it is the case that poor school outcomes lead to migration, weaker students who stay in the village would at least have the opportunity to attend school should their interest or performance improve. It is important to note that attending school at migration destinations is not really an option for migrant kids — most migration trips are short, averaging about a month, and parents often change locations from trip to trip, or work for more than one employer during the same trip.

The factor that best explains whether or not a given child migrated in the past year is whether or not his or her mother migrated. Thus, it may make sense for policies that try to address child migration to focus on giving mothers a reason to stay home. The survey suggested that a strong MNREGA programme might be a way to do that. In another analysis of these data, Papp (2012) examines the effects of MNREGA work on migration. He finds a high demand for MNREGA work among migrants despite a large gap between the migration wage and the MNREGA wage.

At the time of the study, women were taking advantage of fairly strong MNREGA programmes in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, but there was hardly any MNREGA work in Gujarat. Across the three states, though, the availability of MNREGA work fell far short of demand - the average adult aged 14 to 69 worked an average of 11 days on MNREGA projects in the summer before the survey, but would have liked to work 44 days. Therefore, this research suggests that expanding access to MNREGA might be a useful way to convince parents, and especially mothers, to migrate for shorter periods or not at all. Less migration would diminish the need for non-parental child care, and may improve education levels among children.

Notes:

- MNREGA provides a legal guarantee for at least 100 days of employment in every financial year to adult members of any rural household willing to do unskilled manual work at the notified wage.

Further Reading

- Banerjee, A. and E. Duflo (2007), “The economic lives of the poor”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), pp. 141–167.

- Breman, J. (1996), Footloose Labour: Working In India´s Informal Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coffey, D., J. Papp, and D. Spears (2013). ‘Short-term Labor Migration from Rural, Northwest India: Evidence from New Survey Data’, http://riceinstitute.org/wordpress/research/?did=12

- Coffey, D. (2013), “Children’s welfare and short term migration from rural India”, Journal of Development Studies, 49(8), pp. 1101-1117 available: http://riceinstitute.org/wordpress/research/?did=4

- Gupta, J. (2003), “Labour in brick kilns: Need for regulation”, Economic & Political Weekly, 38(31), pp. 3282–3292.

- Haberfeld, Y., R. K. Menaria, B. B. Sahoo, and R. N. Vyas (1999), “Seasonal migration of rural labor in India”, Population Research and Policy Review , 18, pp. 473–489.

- Mosse, D., S. Gupta, M. Mehta, V. Shah, and J. Rees (2002), “Brokered livelihoods: Debt, labour migration and development in tribal western India”, Journal of Development Studies, 38(5), pp. 59–88.

- Papp, J. (2012), ‘Essays on India’s Employment Guarantee.’, Ph. D. thesis, Princeton University.

- Rogaly, B. (1998), “Workers on the move: Seasonal migration and changing social relations in rural India”, Gender and Development, 6(1), pp. 21–29.

07 October, 2013

07 October, 2013

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.