Poverty measurement at the household level assumes that the poverty status of all household members, irrespective of age and gender, is the same as that of the household. This column presents a framework to measure multidimensional poverty at the individual level and finds that intra-household inequality in poverty measures vastly increases the differences in poverty rates between genders and across age groups. The framework is especially important given that the World Bank plans to measure poverty rates for men and women separately.

Poverty and inequality measures are used to track trends in well-being, target social and economic programmes, and measure the impact of interventions. Poverty can be measured either at the household or at the individual level. When measuring poverty at the household level, the poverty status of all individuals in the household is assumed to be the same as that of the household. This implicitly assumes that resources are distributed equally, or according to need, within the household. But these assumptions are inconsistent with the theoretical literature and empirical evidence on intra-household bargaining, which has shown that well-being outcomes depend on the bargaining power within the household. As males and females, and people of different age groups, often live together in households, inequalities in their access to resources is simply assumed away in such household-level analyses. Consequently, the gender or age-segregated poverty numbers obtained from these calculations are unreliable at best and deeply misleading at worst. And even overall poverty numbers, trends, and correlates might be similarly affected.

Within-household inequality in resource distribution has been acknowledged in the literature for long, but there have been only few attempts at measuring poverty and inequality using truly individual-level achievements. The dominant approaches in both unidimensional income and multidimensional poverty measurement use the household as the unit of analysis to determine poverty status of individuals. Measuring individual poverty in the unidimensional income space is difficult as household-level public goods can be potentially shared by all members of households and are difficult to ascribe to individuals. But several non-income achievements are measured at the individual level in household surveys and can be directly used to construct individual-based estimates. There have been some survey-based multidimensional measures proposed exclusively for different demographic groups within the population (Alkire et al. 2013, Roche 2013, Vijaya, Lahoti and Swaminathan 2014), but most focus only on a subset of the population like women or children or adults.

Issues with household-level poverty measurement

The bias inherent in household-based analysis depends on how the thresholds for household poverty in a dimension are set, or how the individual-level data is used to create a household-level indicator. To understand this better we classify the thresholds, below which households are deemed poor, into two categories – restrictive and expansive.

Restrictive thresholds are where the achievement of the worst-off member of the household has to be above the threshold for the household to be non-deprived. In these cases the deprivation rates among individuals are overestimated by household measures as long as not all households are indeed equally deprived in that dimension. An example of a restrictive threshold definition is the nutrition threshold in the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). The household is deemed deprived in nutrition if any child under the age of five or any adult in the household is under-nourished. Presence of just one under-nourished individual in the household will result in all other well-nourished individuals in the household to be deemed as deprived. Hence the nutrition deprivation rate among individuals is overestimated in the household-based MPI measure; in our empirical application for India it is overestimated by 25 percentage points.

Expansive thresholds are where only the achievement of the best-off individual has to be above the threshold for the household to be non-deprived. In such cases, the deprivation rates among individuals are underestimated by household measures if not all are as well off as the best-off. Education deprivation is defined in an expansive way in standard MPI measures. Household is deemed non-deprived in education dimension if just one individual in the household has completed six years of education. This definition would result in all individuals in the household who have less than six years of schooling to be deemed as non-deprived just due to the presence of one individual in the household with five or more years of education. The education deprivation rate among individuals is underestimated in household-based MPI measures by 26 percentage points in India. UNDP and OPHI´s (Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative) MPI use a mix of indicator threshold definitions – restrictive and expansive – so that the net bias of their neglect of intra-household inequality is not clear a priori.

Measuring multidimensional poverty at the individual level

In our paper, we present a framework to measure multidimensional poverty and inequality at the individual level that accounts for intra-household inequality across the entire population (Klasen and Lahoti 2016). We construct an individual-level MPI that directly uses individual achievements for education, nutrition and some aspects of living standards dimensions (particularly the burden associated with water-fetching due to lack of access, and the burden suffered from unclean cooking fuels). This multidimensional measure is then compared with a household-based MPI measure that uses the same dimensions and indicators as the individual MPI, but thresholds are defined at the household level. We use data from the 2012 Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) to operationalise this framework and test the results for India.

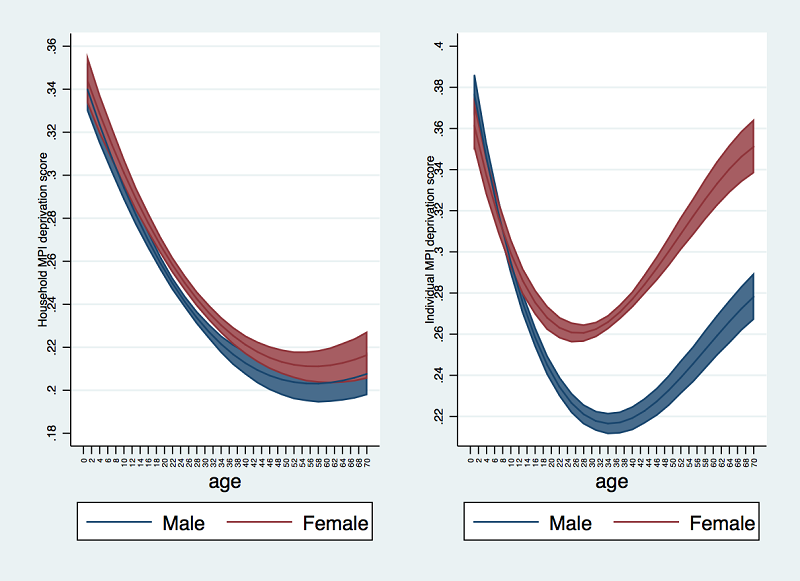

Figure 1. Multidimensional deprivation scores by age and sex

We find that women and older individuals in India are far more deprived and poor than men and younger individuals, and most of this is driven by the education dimension, as shown in the right-hand panel of Figure 1. This finding is absent in the household-based measures as shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 1. As a result, the poverty rate of females is higher by 14 percentage points than men in our individual MPI measure but only 2 percentage points higher when using the household-based measure. Similarly, poverty rate among individuals aged 50 and over is higher by 46 percentage points than among children aged between 7 and 18 years of age in the individual measure, compared to only 2 percentage points when using the household-based measure. We also find that there is no measurable gender differential in deprivation or poverty status for younger individuals, but for the older generation these differences are large as shown in Figure 1. The differences between men and women are driven by education deprivation, and these are non-existent for children up to the age of 15 but increase substantially for adults with age. The push in recent years by the government to enroll more students and increase access to schools has helped in almost eliminating the gender gap in schooling. We do not find significant differences in nutrition status by gender, but the time-use indicators for water collection and cooking suggest that women are the ones who suffer most from lack of access to water and clean cooking fuel.

We also find that intra-household inequality which was assumed to be zero in the household-based measures is actually 30% of total inequality in multidimensional poverty among individuals. Also, inequality in deprivation scores across the population is 30% higher using the individual-based measure.

Implications for policy

Our paper shows that existing household surveys can be used to individualise multi-dimensional poverty measurement, at least to some extent, and that widely-used household-based MPI measures from UNDP and OPHI might give biased estimates of the extent and distribution of poverty and inequality, especially in countries with large intra-household inequality. At the same time, we recognise that our individual measure suffers from lack of individual data on several aspects in standard household surveys. Improved individual data would likely improve our understanding of deprivations suffered by individuals.

Measurement of poverty at the individual rather than household level also has policy implications in terms of dimensions to focus on for reducing multidimensional poverty and also whom to target for poverty-alleviation programmes. Using individual poverty measure policymakers would be advised to focus on reducing education deprivation as it is the biggest contributor to poverty, whereas health would be the focus if we use household-based poverty measures. Almost a quarter of individuals are misidentified (either as poor or non-poor) using the household-based measure, leading to poor individuals being potentially excluded from benefits of poverty alleviation programmes.

Commission on Global Poverty, a high-level commission headed by Sir Anthony Atkinson to advise the World Bank on how to measure and monitor global poverty, has recommended that the bank also calculate the number of women, children and young adults living in poverty. Our framework provides a way to measure poverty so that it can be meaningfully disaggregated by gender and age.

Further Reading

- Alkire, Sabina, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Amber Peterman, Agnes Quisumbing, Greg Seymour and Ana Vaz (2013), “The women’s empowerment in agriculture index”, World Development, 52, 71-91.

- Klasen, S and R Lahoti (2016), ‘How Serious is the Neglect of Intra-Household Inequality in Multi-Dimensional Poverty Indices?’, February.

- Roche, José Manuel (2013), “Monitoring progress in child poverty reduction: Methodological insights and illustration to the case study of Bangladesh”, Social Indicators Research, 112(2), 363-390.

- Vijaya, Ramya, Rahul Lahoti and Hema Swaminathan (2014), “Moving from the household to the individual: Multidimensional poverty analysis”, World Development, 59, 70-81.

01 August, 2016

01 August, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.