‘I Paid A bribe’ (ipaidabribe.com) harnesses the collective energy of Indian citizens against corruption by enabling them to report anonymously on the nature, number, pattern, types, location, frequency and values of demands for bribes. In this note, Venkatesh Kannaiah, the editor of IPAB discusses the initiative and the value of technology in tackling corruption, both in India and globally.

Started five years ago, I Paid a Bribe (IPAB) is an online initiative by Janaagraha that focuses on retail corruption. It is now the largest online crowdsourced anti-corruption platform in the world. IPAB uses a community model to collect bribe reports and to build a repository of corruption-related data across government departments. Most importantly, it empowers citizens, governments, and advocacy organisations to tackle retail corruption.

The value of technology in fighting corruption is embodied in the story of Mr Manik Taneja when he reported a bribe that he had paid on ipaidabribe.com and how it empowered him to fight back against the harassment.

Mr Taneja was forced to pay a bribe at the Bengaluru International Airport a few years ago on his return from the US. He was bringing a Kayak back with him and had done background research about the customs duty he would have to pay at the airport. He got a shock when he was asked to pay much more, and when he objected the customs official demanded a bribe.

Mr Taneja, tired after a long transcontinental flight and dazed by the request, put up a spirited argument but finally had to pay the bribe by withdrawing cash from an ATM. He posted his experience on IPAB the very next day, where a reporter at a local daily read it. The reporter contacted the Janaagraha to get the details of the complainant, then ran the story on the front page of his daily newspaper. The customs authorities took note and started investigations into the incident.

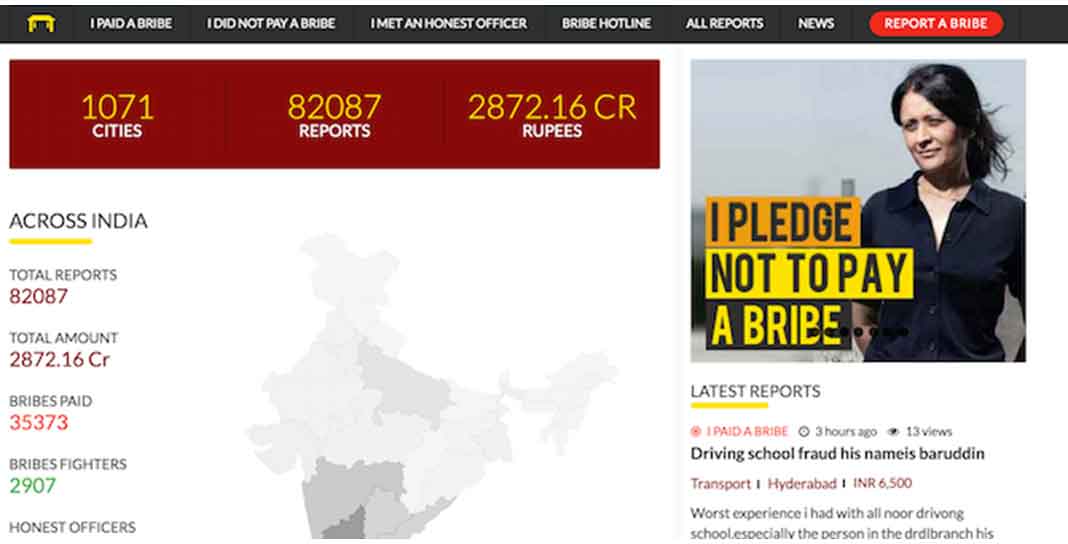

Figure 1. ‘I Paid A Bribe’ website

Technology can fight corruption

Technology aided every step of the investigation. There were the closed circuit cameras, which captured the long argument Mr Taneja had with the official. This combined with the report on IPAB’s online portal and the receipt from the local ATM which showed that he did indeed withdraw the money strengthened Mr. Taneja’s case.

Mr Taneja was persistent in following up with his complaint and tirelessly visited the airport office for a battery of questions. 18 months later, and after 15 visits to the airport office, action was taken and the customs official was suspended.

This is one of the many instances which shows IPAB in action. In a country where it is notoriously difficult for action to be taken against government officials, the platform offered a starting point which eventually resulted in a tangible outcome. Mr Taneja, like many others who have used the portal, now believes in the power of technology to fight corruption.

IPAB has gone international since it was founded and as of March 2016, it has partnered with 25 countries to create replica IPAB sites and is part of an international Crowdsourcing Against Corruption Coalition.

Janaagraha has also appointed a two-member Ombudsman to investigate instances of corruption in India, based on bribe data sourced from the website. The two-member team aims to quicken process reforms by releasing periodic reports on bribes based on the crowdsourced data available on the IPAB website. These are called the Jana Mahiti reports.

One of the recently released JanaMahiti reports talks about corruption in the issue of passports (Janaagraha 2016). It recommends doing away with the manual verification of address of the applicant by a policeman visiting the residence of the applicant, as this usually involves payment of a bribe. After repeated complaints, the government is looking at the issue of passports and is trying to simplify the law.

One of the challenges in India is that government offices do not have closed circuit cameras like Mr Taneja’s case at the airport. The processes are opaque and citizens find it difficult to find information. Most local government processes are still paper-centric, so it is tough to monitor efficiency or performance.

Fears of harassment may inhibit reporting

The government makes it almost impossible for a citizen to file a complaint against a public official and expect action to be taken. What is more, complainants fear that they will be harassed for pursuing the complaint. Unfortunately, this is not an unfounded fear. So the story of Mr Taneja is a common occurrence, and it is so because governments have been lax on fighting corruption among their officials.

However, citizens recognise the power of platforms like IPAB, which have opened the floodgates for reporting bribes anonymously and are a role model for anti-corruption activists using the social media to tackle corruption. With the growth of smartphones and other easy capture devices, social media is already abuzz with videos capturing the antics of bribe takers.

India fares poorly on the transparency indices and on ease of doing business. But the cost for a poor citizen forced to pay a bribe for a service he is entitled to – and the service being given to him because he is below the poverty line – is a greater tragedy.

We at IPAB are keen for the Tanejas of India to use the platform, report the bribe, and use the power of the platform to reach out to larger audiences and finally see legal action taken. But we are not waiting for the Tanejas to land up on their own. We have an active social media presence on Facebook and Twitter and are actively reaching out to people on their smartphones with an Android application, as well as offering the ‘old-fashioned’ SMS to the large number of users who do not have smartphones. We have also experimented with a ‘call-in’ facility where users just dial in a number and report a bribe, for those on the other side of the digital divide, or who feel more comfortable sharing their stories orally.

This article has previously appeared on the SouthAsia@LSE blog and the IGC Blog.

Further Reading

- Janaagraha (2016), ‘Jana Mahiti Report – Passport Verification’, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy.

06 June, 2016

06 June, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.