Violence against women in India has recently been brought to the world’s attention. But for too long the problem has been under reported. This column looks at what the data can tell us.

A recent G20 survey ranked India as the worst place to be a woman (Baldwin 2012). Female foeticide, domestic violence, sexual harassment, and other forms of gender-based violence constitute the reality of most girls’ and women’s lives in India. That domestic violence in India and globally is grossly underreported in surveys and to the police is well known.1 But my recent analysis shows that there is a gap between what is reported in the national surveys such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) and the figures from the police’s National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB).2 How large is this gap and what can it tell us?

My analysis presents some surprising findings

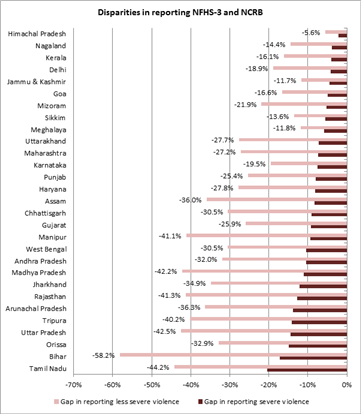

- First, the disparity in reporting of domestic violence between the NFHS-3 and NCRB (2009) ranges from a Difference of around 6% for Himachal Pradesh to a high of 58%in Bihar – that is, in Bihar, half of domestic violence cases reported in surveys are not reported to the police. Perhaps unexpectedly, southern India with greater gender ‘fairness’ has large gaps (44% in Tamil Nadu, 32% in Andhra Pradesh and 20% in Karnataka).

- Second, even within the national survey, the severity of violence is likely to be underemphasised because the correlation between injuries sustained as a result of domestic violence varies very little between severe and less severe instances of abuse.In other words, those reporting ‘less severe’ abuse may in fact be suffering far more.

- Third, despite the provision for the anti-dowry law 304(B) (to prosecute deaths due to dowry harassment) to be read alongside 498(A) (to prosecute domestic violence), this is frequently not the case particularly in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha

Prevalence of violence

According to the national survey, the statistics on violence against women in India are stark. Nationally, 8% of married women have been subject to sexual violence, such as forced sex, 31% of married women have been physically abused in a way defined as ‘less severe’, such as slapping or punching, while 10% have suffered ‘severe domestic violence’, such as burning or attack with a weapon.3 Also, 12% of those who report being physically abused also report at least one of the following injuries as a result of the violence: bruises (D110A), injury, sprains, dislocation or burns (D110B), wounds, broken bones or broken teeth (D110D) and/or severe burns (D110E). With regard to emotional abuse, 14% of Indian women will have experienced this at some point in their lives.4

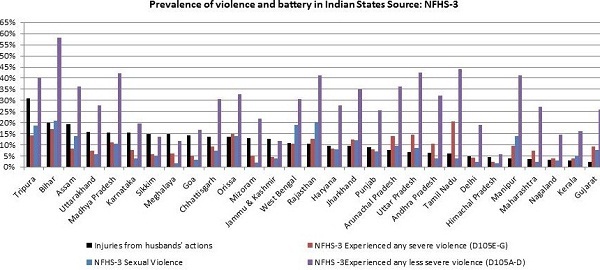

Figure 1 shows that 31% of married women from Tripura, 20% from Bihar, 19% from Assam and 15% from Uttarakhand report injuries as a result of physical violence.5 Above-average rates of less severe domestic violence are reported by women in Bihar, Tamil Nadu, UP, MP, Rajasthan, Manipur, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Jharkhand, Orissa and Andhra Pradesh. With regard to severe instances of domestic violence, the same group of states reappear, with the exception of Assam and Manipur, but including West Bengal. Above-average levels of sexual violence are reported by the same states with the notable exceptions of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu but including Manipur and Assam.

Figure 1. Prevalence of violence and battery in Indian States

Table 1. Correlation coefficients for injuries by type of violence reported

Table 1 above presents the correlations between reported abuse and injuries. It suggests, unsurprisingly, that injuries from violence are correlated with severe violence. What is much more surprising, however, is that the same sort of injuries are similarly correlated with less severe violence.This suggests that the reported severity of violence is not necessarily a good predictor of injuries. In other words, those reporting less severe violence may in fact be hiding the true intensity of their abuse.

Reporting deficit

Analysis of data from NFHS-3 and NCRB indicates that for the most part, instances of domestic violence reported by women in national surveys never make it to the police or the courts.6 While this in itself is not surprising, what is surprising is the extent of this deficit. The states that have the highest reported prevalence of serious injuries – that is, burns, dislocations, strangulations, attack with knives or other weapons, the deficits in police reporting are: 28% in Tamil Nadu, 18% in Bihar, 15% each in Odisha and UP, and 14% each in Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh. With less severe instances of abuse, the gap widens considerably, 58% fewer in Bihar, 44% fewer in Tamil Nadu, 42.5% fewer in UP and 41% fewer in Manipur are reported to the police. Even if we assume that instances of domestic violence that find their way to crime statistics are the most severe instances, it is of significant concern that there are such wide disparities between NFHS-3 reported violence and national crime statistics in many of the states.

Figure 2. Disparities in reporting – national survey and police reports

Rates of dowry and rates of domestic violence in police records

According to the 2009 NCRB figures, the states with the highest rates of dowry deaths7 per 100,000 people are:8 Bihar (1.4), Haryana and MP (1.2 each) and UP (1.1). Despite the fact that dowry deaths should be read with 498(A) since there are provisions within 498(A) to prosecute violence inflicted in order to extract money, durables and other valuables, it is surprising to find that the states with some of the highest reported dowry deaths, have some of the lowest reported rates of domestic violence, and only Rajasthan Delhi and Haryana feature in the top 10 for both. Dowry deaths are often preceded by a period of sustained physical and emotional abuse of victims. However these figures suggest that this is seldom reported to the police; thus domestic violence rates are under-recorded and under-reported in crimes classified as dowry murders despite the expectation that 498(A) should be naturally included with 304(B) both before and after the murder of wives.

Figure 3. Top 10 states for highest percentage of dowry deaths

Figure 4. Top 10 states for highest reported percentage of domestic violence deaths

What do the findings mean?

If exposure to domestic violence is any indicator of quality of life, these figures reveal that the advances in lifestyles for women in southern and north-eastern India over their counterparts in northern India seem to be eroding: above-average levels of violence are reported in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh as well as in Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur. Anthropological and sociological accounts on regional variations in gender issues have found that women in northern India have less autonomy, mobility, less say in household decisions and fewer property rights while those in southern and north-eastern India fare better.9 These differences had been attributed to elements in kinship structure such as village exogamy (marrying outside of a social group), cross-cousin marriages, son preference, purdah,10 wet/dry crop cultivations, land tenure systems, histories of colonisation and other factors.

However Rahman and Rao (2004) found that in the intervening 20 years since Dyson and Moore’s study much has changed and southern advantages with regard to kinship structures, have reduced. Investments by the state in infrastructure, schooling and improving economic opportunities for women has been found to be more effective in empowering women. If the police records were the weathervane for gender equity, then West Bengal and Kerala would be considered some of the worst states to be a woman while Bihar, UP and Odisha would look like good places. How can these incongruences be explained? In effect what we find in the national survey is a more accurate reflection of the extent of physical abuse while levels in the police records are seriously underreported. Additionally, cultures of enumeration and the role of the police could also play a role in explaining some of the differences. This analysis confirms insights from studies that reveal that when women try to file first information reports (FIRs) they are often told that it is a private matter and their injuries are dismissed as minor.11 States such as Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Orissa, UP, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh that have some of the largest reporting disparities particularly for severe violence perhaps have the worst institutional conditions for encouraging police reporting.

The current levels of abuse that many married women across India endure are scandalous and measures must be put in place to rectify it.

Notes:

- See for instance Heise 1998, Ellsberg et al. 2001, ICRW 2001, and Jansen et al. 2004.

- The two primary sources of data are the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS-3) and the National Crime Records Bureau Reports. The base year for analysis is taken as 2009 because it is closest to the 2005 NFHS-3 in terms of chronology. Chi-square tests and other non-parametric tests have been used to identify statistically significant differences.

- The following acts have been classified as sexual violence in the NFHS-3: D105 (H) – ever physical forced sex when not wanted, D105I – ever forced other sexual acts. Less Severe Violence D105A-D105 includes the following acts: spouse ever pushed shook or threw something, spouse ever slapped, spouse ever punched with fist or something harmful and spouse ever kicked or dragged. Severe Domestic Violence D105E-F includes: spouse ever tried to strangle or burn or spouse ever threatened or attacked with knife or gun or other weapon.

- Emotional abuse (D103A-D105C) includes the following acts: spouse has humiliated respondent, spouse has threatened respondent with harm, spouse has insulted respondent or made respondent feel bad.

- Differences between states are statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

- My experience doing qualitative research in a slum in Mumbai indicates that of the 52 women I interviewed in 2005, 20 reported physical violence and none had filed a police complaint (Ghosh 2011).

- Dowry deaths’ are deaths of young women who are murdered or driven to suicide by continuous harassment and torture by husbands and in-laws in an effort to extort an increased dowry.

- The NCRB calculates these figures by dividing the incidence of the particular crime in the state by the estimated mid-year population.

- See for instance Dyson and Moore 1983, Kishor 1993, Malhotra et al. 1995, Das Gupta et al. 1996, Kishor and Neitzel 1996, Jejeebhoy 1996, and Rahman and Rao 2004.

- ‘Purdah’ is the practice of veiling and concealing women from men, especially those unrelated to them.

- See for instance Agnes 1993, Geethadevi 2000, Prasad 1999, and Kethineni and Srinivasan 2009)

Further reading

- Agnes, F (1993), ´Marital murders - the Indian reality.´,Health Millions, 1(1):18-21.

- Baldwin, K (2012), ´Canada best G20 country to be a woman, India worst - TrustLaw poll´, Thomson Reuters, 13 June.

- Das Gupta, M, LC Chen, and TN Krishnan (1996), Health, poverty, and development in India , Oxford University Press.

- Dyson, T and M Moore (1983), ´On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India´, Population and >Development Review , 9(1):35-60.

- Ellsberg, M, L Heise, R Pena, S Agurto, and A Winkvist (2001), ´Researching Domestic Violence Against Women: Methodological and Ethical Considerations´, Studies in Family Planning, 32(1):1.

- Geethadevi, M, R Raghunandan, and Shobha from Vimochana (2000), ´Getting Away with Murder: How Law Courts and Police Fail Victims of Domestic Violence´, Manushi: A Journal about Women and Society , 117:13-41.

- Ghosh, S (2011), ´Watching, Blaming, Silencing, Intervening: Exploring the role of the community in preventing domestic violence in India´, Practicing Anthropology, 33(3):22-26.

- Heise, LL (1998), ´Violence against women: An Integrated Ecological Framework´, Violence Against Women, 4(3):262-290.

- ICRW (2001), ´Domestic Violence in India II: Exploring Strategies, Promoting Dialogue´, in ICRW Information Bulletin.

- Jansen, HAFM, C Watts, M Ellsberg, L Heise, and C Garci-Moreno (2004), ´Interviewer Training in the WHO Multi-Country Study on

- Women´s Health and Domestic Violence´, Violence Against Women, 10(7):831.

- Jejeebhoy, SJ (1996), Women´s education, autonomy, and reproductive behaviour : assessing what we have learned.

- Kethineni, S, and M Srinivasan (2009), ´Police Handling of Domestic Violence Cases in Tamil Nadu, India´, Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 25(2):202-213.

- Kishor, S (1993), ´´May God Give Sons to All´: Gender and Child Mortality in India´, American Sociological Review , 58:247-265.

- Kishor, S and K Neitzel (1996), The status of women: Indicators for 25 countries , Demographic and Health Surveys comparative studies, No. 21, Macro International Inc.

- Malhotra, A, R Vanneman, and S Kishor (1995), ´Fertility, Dimensions of Patriarchy, and Development in India´, Population and Development Review, 21(2):281-305.

- Prasad, S (1999), ´Medicolegal response to violence against women in India´, Violence Against Women, 5(5):478-506.

- Rahman, L and V Rao (2004), ´The Determinants of Gender Equity in India: Examining Dyson and Moore´s Thesis with New Data´, Population and Development Review , 30(2):239-268.

11 February, 2013

11 February, 2013

By: Amita Arya 25 March, 2021

With my experience of working with rural women, there is a so much of acceptance of violence against women in the culture that it is not even considered wrong. A women will show her bruises in private, but as soon as the husband comes, she would lie saying he hasnt hurt her for last one year.. so i do not believe the data, it may only tell that the problem is grave and needs to be addressed.