Indians, particularly men seeking education and jobs, display a puzzling reluctance to cross state borders. This article explores the reasons for this migration pattern. A major culprit is India’s system of ‘fragmented entitlements’, whereby welfare benefits are administered at the state level, and state residents get preferential treatment in higher education and government employment. These administrative rules prevent more efficient allocation of labour across the country.

Migration facilitates growth and poverty reduction through the more efficient allocation of labour to more productive opportunities. It is

That international borders, the focus of considerable political attention in recent years, limit migration is obvious. But we would not expect provincial or state borders to prevent people from moving within a country. Most countries do not impose restrictions on internal mobility – China’s ‘hukou’ system being the best-known exception. In many cases, freedom of movement is a constitutionally protected right. In this regard, India presents a puzzle (Munshi and Rosenzweig 2016).

In 2001, internal migrants represented 30% of India’s population, but this number is deceptively large. Two-thirds were migrants within districts (an administrative unit within a state), and more than half were women migrating for marriage. Internal migration rates across states were nearly four times higher in Brazil and China, and more than nine times higher in the US in the five years ending in 2001 (or 2000). In fact, India ranked last in a comparison of internal migration, in a sample of 80 countries over five year-year intervals between 2000 and 2010 (Bell et al. 2015).

In recent research, we find evidence of ‘invisible walls’ between Indian states (Kone et al. 2017). Indians, particularly men, seeking education and jobs reveal a surprising reluctance to move to another state. To understand and explore the causes of this pattern, we worked with the Indian Census authorities and obtained unique data from the 2001 Census on district-to-district migration between each pair of India’s 585 districts. These data were further disaggregated by age, education, duration of stay, and

District-to-district migration data have several advantages. Most existing studies of migration in India use household survey data, which suffer from sampling and aggregation biases and rarely capture bilateral flows. Other studies use proxies for migration, like railway passenger data as in Government of India (2017). These datasets cannot precisely measure bilateral migration and distinguish between different durations, education levels, and motivations of migrants.

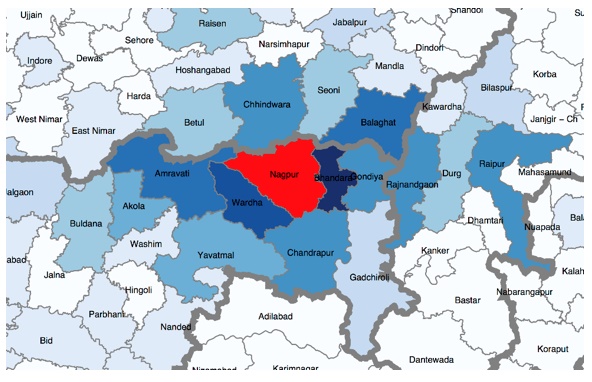

To illustrate the (restrictive) role of state borders on internal migration, consider the district of Nagpur in Maharashtra. Nagpur is geographically located at the centre of India and close to three other states: Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. Figure 1 plots the color-coded distribution of the origin districts of the migrants coming to Nagpur, with darker shades implying higher shares of migrants. The thin lines represent district borders and thick lines are the state borders. The four neighbouring districts in Maharashtra (Bhandara, Wardha, Amravati, and Chandrapur) sent a total of 31% of Nagpur’s immigrants. In contrast, the remaining three neighbouring districts in Madhya Pradesh (Balaghat, Chhindwara, and Seoni) sent a total of only 13%. More migrants came to Nagpur from other districts in Maharashtra that are hundreds of kilometres away than from neighbouring districts in other states.

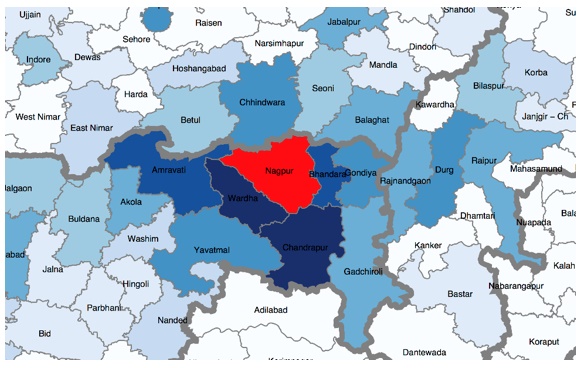

Similar patterns are observed when we look at out-migration from Nagpur to other districts in Figure 2. The most popular destinations of Nagpur’s emigrants are again the four neighbouring districts in Maharashtra, which receive a total of 32% of emigrants. Neighbouring districts in other states receive much fewer

Figure 1. Origins of in-migrants in Nagpur

Figure 2. Destinations of out-migrants from Nagpur

In our econometric analysis based on a gravity model, our detailed district-to-district migration data allows us to control for origin- and destination-specific factors (such as natural resource endowments, economic and social conditions, and climate) through fixed effects. Thus, we can focus on the bilateral variables, including the critical contiguity variables – being in the same state and/or

We find that migration between neighbouring districts in the same state is at least 50% larger than migration between districts that are on different sides of a state border. Although the impact of state borders differs by education, age, and

The low level of internal mobility in India is a puzzle because there are no explicit restrictions imposed by the state or federal governments. We find preliminary evidence that indicates that mobility in India is inhibited by explicit and implicit entitlement programmes implemented at the state level.

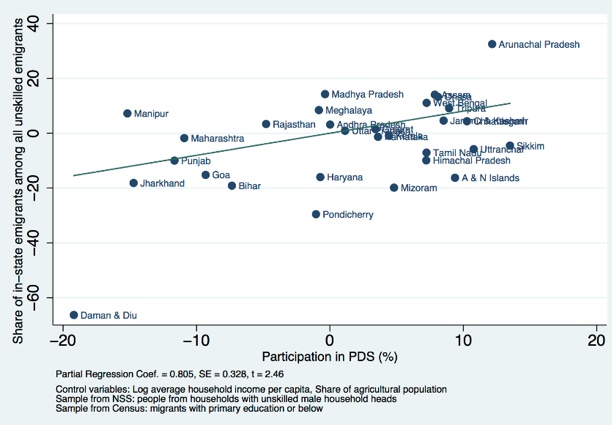

First, many social benefits are not portable across state boundaries, even if they are federally

Figure 3. Participation in the PDS and unskilled out-migration

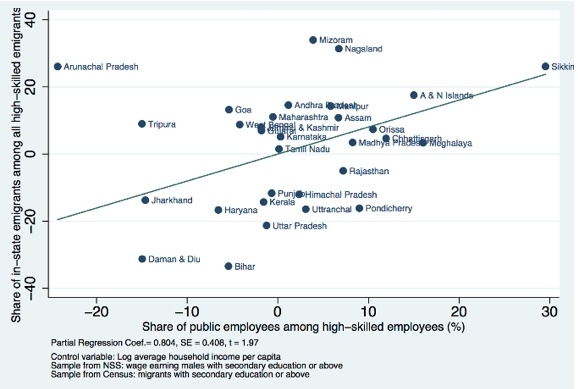

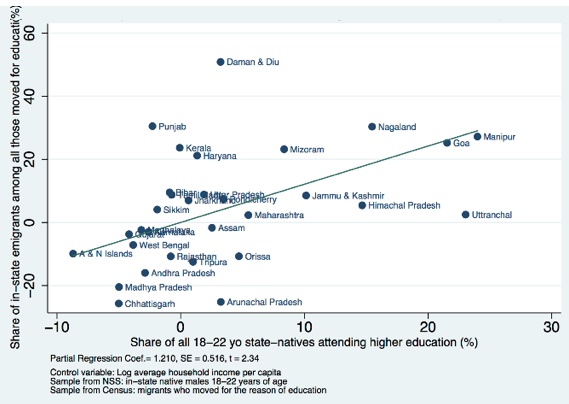

While non-portability of such benefits inhibits the movement of the poor and the unskilled, two other factors contribute to the inertia of the skilled. Many universities and technical institutes are administered by the state governments, and state residents get preferential admission. Furthermore, government jobs account for more than half of the employment opportunities for individuals with higher education. State domicile is a common requirement for employment in such government entities across the country. In fact, the relative share of skilled migrants moving out-of-state is lower in states with higher rates of public employment (Figure 4). And the relative share of migrants moving to other states to seek higher education is lower in states with higher rates of access to tertiary education (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Public sector employment and skilled out-migration

Figure 5. Tertiary school attendance and out-migration for education

As we note, internal mobility is critical for development and poverty reduction, especially for a country like India, which has the second largest labour market in the world and hundreds of millions of people living in poverty. India’s ‘fragmented entitlements’ – that is, state-level administration of welfare benefits, as well as education and employment preferences – are likely to dampen growth by preventing the efficient allocation of labour. The introduction of a unique national identification system, the Aadhaar card, is likely to lower but not eliminate the costs of moving. A bigger boost to mobility would come from reforms, that make welfare benefits fully portable and end state-biased recruitment to jobs and admissions to educational institutions.

The article first appeared in VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/how-india-s-internal-borders-inhibit-migration

Further Reading

- Bell, Martin, Elin Charles-Edwards, Philipp Ueffing, John Stillwell, Marek Kupiszewski and Dorota Kupiszewska (2015), “Internal migration and development: comparing migration intensities around the world”, Population and Development Review, 41(1): 33–58. Available here.

Government of India (2017), ’India on the move and churning: New evidence’, Chapter 12 in Economic Survey, Ministry of Finance.- Kone, ZL, A Mattoo, C Ozden and S Sharma (2017), ’Internal borders and migration in India’, World Bank Policy Research working paper No. WPS 8244. (forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Geography).

- Munshi, Kaivan and Mark Rosenzweig (2016), “Networks and misallocation: Insurance, migration, and the rural-urban wage gap”, American Economic Review, 106(1): 46–98.

25 May, 2018

25 May, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.