India has one of the most ambitious targets for forest cover as part of its Nationally Determined Contributions to the Paris Agreement which will require considerable land and financial resources. In this post, Shubham Sharma argues that mere creation of a fund for compensatory afforestation, when natural forests are diverted for development might not be the best solution. Integrated solutions are required to address the causes of diversion of forest land.

India has committed to create an additional carbon sink of 2.5-3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover in its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)1 to the Paris Agreement2. The achievement of this target will entail conservation of existing forests and acquisition of land for creating additional forests. While the amount of money required to achieve such a target will be high, the real challenge will be the availability of land for afforestation. To put it in perspective, among the top 10 countries in the world with largest forest area, India has the highest population density (409 people per square kilometre) followed by China (145 people per square kilometre). Despite increasing population, India has managed to increase its forest cover due to legal provisions which include compensatory afforestation (CA) and collection of CA funds (also called CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority) funds) from the proponent (government or private) seeking diversion of forest land.3 These funds have been under heavy scrutiny over their underutilisation by state governments. These issues of utilisation led the Supreme Court to direct the Union government to establish an authority to manage these funds. In 2016, Union government passed a bill for the establishment of an authority for management of these funds which amount to more than Rs. 600 billion. Since then there have been constant questions over the guidelines for utilisation of these funds and related issues such as the definition of ‘non-forest land’ to be identified for the purpose of afforestation. However, the unavailability of land for afforestation might be the most pressing concern.

The state government of Haryana, earlier in 2018, demanded the central government to remove the 10% withdrawal cap on the CAMPA funds to allow purchase of land for the purpose of afforestation. When the Supreme Court was considering affidavits filed by the state governments of Odisha and Meghalaya, it expressed concern over the usage of these funds. Another concern is the acquisition of land for afforestation such that the sanctity of other acts, notably Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, remains unperturbed. In order to address these issues Government of India notified the rules and regulations for the Compensatory Afforestation Fund (CAF) Act, 2016 on 10 August 2018. The Act came into force on 30 September 2018 but the potency of the Act to address the causes of diversion of forest land remains unclear.

Land for compensatory afforestation

The Forest Conservation Act of 1980 addresses the issue of land under the section 3.2 titled ‘Land for Compensatory Afforestation’ but does not clearly define the term ‘non-forest land’. It states that afforestation must be carried out on the non-forest land identified contiguous or in the proximity of ‘Reserved Forest’ or ‘Protected Forest’4, as much as possible. In case, non-forest land for CA is not available in the same district, it is to be identified elsewhere in the state/Union Territory (UT). If non-forest land is not available in the entire state/UT, funds for CA, in double the area than the extent of the forest land diverted for non-forestry purpose, need to be provided by the user agency5. The Act also includes certain further directives in case of non-availability of land and for compensation in case of certain projects, for example, central government projects, minor irrigation, link roads, riverbed mineral extraction, etc.

The lack of clarity over the definition of non-forest land in the Act forced the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) to come out with a notification in November 2017 which defined non-forest land to include revenue land, zudpi jungle (scrub forest), chhote-bade jhar ka jungle/ jungle-jhari land (open forest), civil-soyam land (tertiary mortgaged land) and all other such categories of lands.

Current status

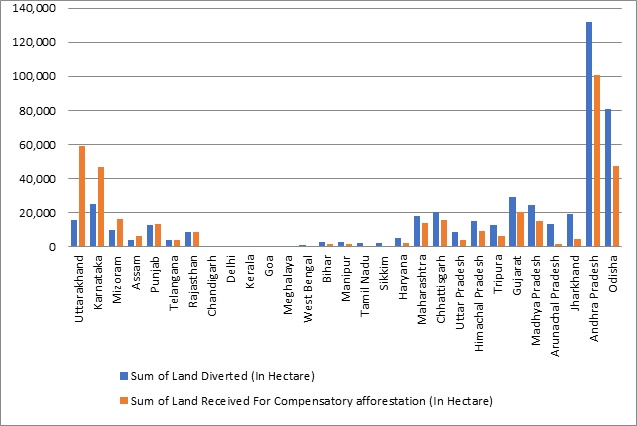

As per the government’s e-governance portal for forestry and plantation, e-green watch, the total land acquired for afforestation is almost half of the total land diverted in case of Haryana. At the country level too, the total forest land diverted is significantly greater than the total land received for afforestation. It defies the purpose of CA which is to compensate the loss ‘land by land’ and ‘tree by tree’. Also since the land identified for CA by the forest department is declared as Reserved Forest or Protected Forest, thus transferring its land rights to the department, there are concerns over the rights of forest dwellers and tribals (under Recognition of Forest Rights Act, 2006).

It is important to note that the CAMPA Act as passed by the government doesn’t strictly adhere to the judgement of the honourable Supreme Court of India. The judgement clearly mentions that the fund generated for protecting ecology and providing regeneration should not be treated as the consolidated funds6 (Article 266 and 283). But the Act as passed in 2016 clearly treats these funds as the consolidated funds further diluting the primary objective of creating a special fund and allowing divergence of funds for non-forestry purposes.

The unavailability of land and the divergence of funds for other activities by the state governments raise the concerns over the purposeful utilisation of these funds. Imagine the diversion of forests for the construction of a road and the subsequent use of compensatory funds for infrastructure development (construction of a road) in a national park. In such cases, it would be more fitting to term the compensation ‘road by road’ than ‘tree by tree’ or ‘land by land’. Since 1980, 22 states out of a total 29, received less than 100% of forest land diverted, and 11 of these states have received less than 50% of land. Small states like Delhi and Goa have not received any land as a compensation of total forest land diverted, as per the information available on the government’s portal e-green watch.

Figure 1. State-wise account of total forest land diverted and non-forest land received since 1980

Causes of diversion

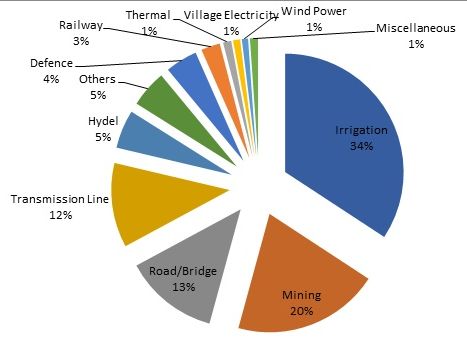

Since 1980, according to the information available on the portal, most of the forest land has been diverted for the irrigation projects (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Type of projects responsible for diversion of forest land (% of total land diverted since 1980)

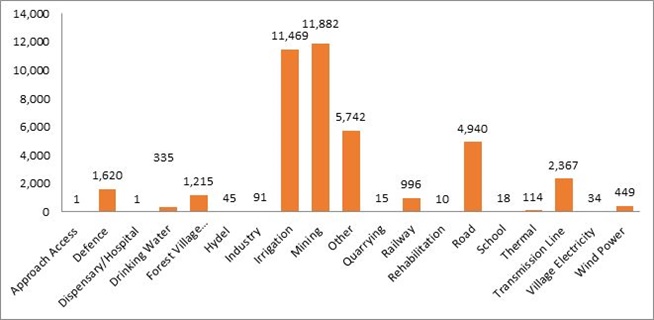

As per the Economic survey (2017-2018), the unirrigated areas in the country will be affected more severely due to climate change. As of 2013-14, the total area under irrigation in the country was 51.9%. The demand of irrigation projects might continue to grow, which is also evident from the data of forest land diverted for the year of 2017-18 (Figure 3). Irrigation projects are followed by mining, road/bridge, and transmission line projects. According to a Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) report, in the Central Indian and Eastern Ghats Tiger landscapes alone, there are approximately 400 projects costing Rs. 1,300 billion, which are likely to result in forest-land diversion (and negatively impact tiger corridors). Clearly, the primary causes of forest diversion are not dispensable and may cause irreparable damage to the natural forests in the country.

Figure 3. Forest land diverted in 2017 under different projects (in hectare)

Way forward

The WCT report calls for integrated policy frameworks to strike a balance between developmental projects and conservation, with a focus on development of green infrastructure. An integrated approach in the case of irrigation, agriculture, and forests will fall under the purview of at least three ministries, namely, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare; Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change; and Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation. If the issues of rural development and tribal affairs are included as per the scope of the integrated framework, as many as five ministries would have to converge for the formulation and implementation of an integrated policy. In such scenarios, the institutions like NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog assume utmost importance. With the availability of CAMPA funds, there exists a potential opportunity for shifting focus to a more integrated approach such as landscape management to address the causes of diversion. It could encompass solutions to efficiently utilise the available resources, mainly land, water, and forests. The literature on integrated landscape management has focused on integrated management of irrigation, fisheries, sustainable land and water management (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2017). But in this case, the states and the Centre must finance research and pilots to promote integrated landscape management with focus on irrigation, developmental projects, and forests. Most of the irrigation projects involve construction of irrigation tank, canals, and check dams which are predominantly concrete structures. It is important to integrate traditional tanks (earthen bounded reservoirs constructed across slopes by taking advantage of local depressions and mounds), and wetlands in the irrigation system to achieve an optimum trade-off.

Conclusion

We cannot do away with the developmental projects to conserve forests, for instance, irrigation is important for ensuring food security and building resilience to climate change. On the other hand, India has a target to create an additional sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030. Hence, mere compensation of money for CA in lieu of natural forests might not be the best solution. The constant accumulation of funds shows that the money is not the problem for user agencies. It could be assumed that the expenditures will be wiser with the newly notified rules and clear guidelines over the expenditure of funds. However, the guidelines over the expenditure focus solely on the forest management and lack vision (soil conservation activities and supply of wood-saving cooking appliances being the notable exception). The true success of the Act will lie in the utilisation of funds to address the causes (whether irrigation, infrastructure or mining projects) of forest-land diversion by focusing on integrated solutions.

Notes:

- NDCs are the targets prepared, communicated, and maintained by each country party to the Paris Agreement to address the issue of climate change.

- Paris Agreement was reached at the 21st yearly session of Conference of Parties (COP21) to the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Paris, on 12 December 2015. The parties agreed to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change.

- Compensatory afforestation has been provisioned by Forest Conservation Act of 1980 which mandates that whenever a forest land is diverted for non-forestry purposes, equivalent non-forest land must be identified for compensatory afforestation. Compensatory Afforestation Fund (CAF) was created to compensate for the loss of tangible as well as intangible benefits from the forest lands which were diverted for non-forest use.

- Reserved Forests and Protected Forests are constituted by states governments. Land rights to forests declared as reserved or protected are owned by the government. A major difference between these forests is the rights to activities (such as hunting, grazing, etc.) which are banned in reserve forests and allowed in protected forests.

- User Agency is the agency (private/governmental) which proposes the diversion of the forest land for non-forestry purposes such as irrigation, mining, construction of roads, etc.

- Consolidated fund refers to all the revenues received by the government by way of taxes and other receipts flowing to the government in connection with the conduct of government business.

Further Reading

- Wildlife Conservation Trust (2018), ‘Central India & Eastern Ghats Report’, Connectivity Conservation India.

- Government of India (2017), ‘Identification and suitability of Non-forest land for Compensatory Afforestation under Forest Conservation Act 1980 – regarding Identification of Land Bank for Compensatory Afforestation (CA)’, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (Forest Conservation Division), 8 November 2017, New Delhi.

- Government of India and United Nations Development Programme (2014), ‘Forest Rights Act, 2006: Act, Rules and Guidelines’, Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

- Government of India (2018), ‘Economic Survey 2017-18’, Ministry of Finance, New Delhi.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2017), ‘Landscapes for life Approaches to landscape management for sustainable food and agriculture’, Rome.

10 April, 2019

10 April, 2019

By: Sophia Roy Choudhury 16 April, 2020

Dear Friend\r\nThank you for this post.\r\nI am a Mother of a Martyr Capt Sameer Roy Choudhury of the Indian Army .We live in Secunderabad, Telangana.\r\nI have a dream of planting a tropical forest in a few acres of land.Here individuals will be taught the Stewardship of Mother Earth, caring for forests with other spiritual (not religious) life lessons.\r\nI wish to know if you can help me identify areas of land for forestation that can be donated by private or government bodies as well as aid for setting up and sustaining the project.\r\nI have come upon this article after searching for many months.\r\nPlease let me know if and how you can help me.\r\nBlessings\r\nSophia Roy Choudhury\r\n