India was recently ranked 174th out of 178 countries, on air pollution. A key contributing factor is diesel vehicles. This column shows that diesel subsidies benefit the rich more than the poor, and emphasises the need to change current regulation to enforce fuel improvement measures. Although such policies seem expensive, the positive effects on sickness, health expenditures and productivity would outweigh the costs.

In recent years, whenever there has been talk of cutting petroleum subsidies in India, there has been a clamour in the press about the allegedly regressive nature of such cuts. Usually, the clamour is loudest with regard to diesel since it is obvious that the poor don’t own vehicles that consume petrol and that they cook with solid fuels such as wood and agricultural waste rather than gas. Diesel, however, is largely used for transport of goods, and the poor do consume goods, although far fewer than the rich. So it may appear possible, if perhaps somewhat unlikely, that cutting diesel subsidies could be regressive.

Diesel is not the poor man’s fuel

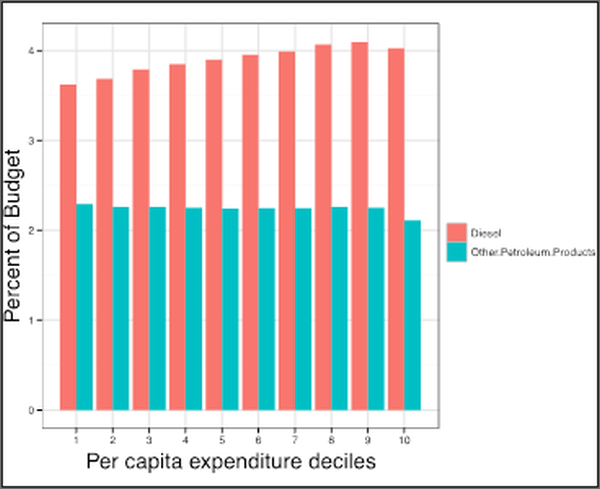

However, as Datta (2008) has shown using National Sample Survey (NSS) data on household consumption from 2004-2005, the share of diesel in per capita consumption expenditure rises as one moves up the deciles (except from the 9th to the top decile)1after taking into account indirect consumption of diesel via the consumption of goods that use diesel for transport2(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Shares of diesel and other petroleum products (including kerosene) in household budgets, taking indirect consumption into account

Although most people remain unaware of these numbers, the increasing number of luxury diesel cars on the street has finally dented the incorrect image of diesel as the poor man’s fuel. Perhaps this has contributed to the implementation of a policy to gradually allow the price of diesel to rise at the rate of Rs. 0.50/litre per month. There is still at this time a price wedge of about Rs. 20/litre so that petrol is about 40% more expensive than diesel.

Mitigating the polluting effects of diesel

Given its regressivity, it is clear that there is little to be said in favour of the diesel subsidy. However, it is important to realise that although the government motivation for reducing the subsidy appears to be wholly fiscal, diesel is a very polluting fuel. It kills a lot of people due to emissions of fine particulate matter (PM2.5 – particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 microns) and other pollutants. Fine particles have lots of toxic chemicals adhering to them and penetrate deep into the lungs. They are implicated in elevated risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

With current technologies, reducing particulate emissions can be most cost-effectively done by reducing the sulphur content of diesel and simultaneously adopting end-of-pipe technologies in vehicles – some combination of diesel particulate filters, lean NOx traps3, and selective catalytic reduction4. The latter does not work well given the currently high sulphur content of most diesel used in India – 350 parts per million. A recent study published by the International Council on Clean Transportation finds that at least 535,000 deaths between 2012 and 2030 could be avoided by re-jigging refineries to produce ultra-low-sulphur-diesel (<10 ppm sulphur) and requiring the use of end-of-pipe technologies in new vehicles. These measures would reduce emissions of PM2.5 from diesel and petrol vehicles by 87% in 2030, relative to no change in current regulations.

Costs vs. benefits

The fuel measures outlined above would cost around Rs. 5,500 crores ($0.9 bn approx.) annually. This sounds like a lot, but it could be wholly financed by an increase in diesel and petrol prices of about Rs 0.50/litre, about 1% of the current price of diesel. The cost of the vehicle regulations would add about 5% to car and 3% to truck prices.

Once one takes effects on sickness, health expenditures, and productivity from reduced pollution into account, these policies look like a bargain. Lacking health insurance, sickness can be devastating for the poor, because of out-of-pocket expenses for often ineffective treatment. Sulphate particles have also been implicated in weakening the monsoon and reducing rice production by a few percentage points over the last four decades. That Delhi has now overtaken Beijing in the air pollution rankings can’t be doing the tourism industry any good either.

Concluding remarks

We shouldn’t leave anyone with the wrong impression that diesel and petrol are the only significant sources of air pollution in India. They may account for less than a third of it, although this depends on which pollutant you measure – diesel is worse in terms of PM2.5. Coal-fired power plants, wood and agricultural waste burnt for cooking and heating, and open burning of agricultural residue are other significant sources.

Notes:

- If all households in the population are ranked in ascending order according to their consumption levels, and then the entire population is divided into 10 equal groups (each comprising approximately 10% of the total population) – the 10th decile will comprise the top 10% in terms of consumption.

- The paper adjusts for indirect consumption using the Central Statistical Organisation’s (CSO) input-output tables.

- NOx is a generic term for mono-nitrogen oxides - NO (nitric oxide) and NO2 (nitrogen dioxide). They are produced from the reaction of nitrogen and oxygen gases in the air during combustion, especially at high temperatures.

- Selective catalytic reduction is a means of converting nitrogen oxides, also referred to as NOx with the aid of a catalyst into diatomic nitrogen, N2, and water, H2O.

- PPM stands for ‘parts per million’.

Further Reading

- Datta, A. (2010), ‘Essays in Environmental Policy’, Ph.D. Thesis, Indian Statistical Institute.

- Datta, A. (2008), “The incidence of fuel taxation in India”, Indian Statistical Institute.

31 March, 2014

31 March, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.