In this post, Chaudhary and Iyer discuss the administrative decentralisation reforms brought about by the Panchayati Raj Act, and measure the effect of decentralisation on the provision of public services and human development outcomes. States implemented these decentralisation reforms at different times, and to different extents. Their findings show that devolution of only functions to the local level, without a devolution of functionaries or funds, results in a decline in the quality of public service.

In 1993, India’s constitution was amended to implement the Panchayati Raj Act, a comprehensive programme of administrative, fiscal and political decentralisation. Administrative decentralisation refers to the transfer of responsibility for providing public services from the central government and its agencies to lower levels of government. It is distinct from fiscal decentralisation, which involves the transfer of tax and spend powers to lower levels of government. It is also distinct from political decentralisation, which refers to local governments being elected by their citizens.

India’s administrative decentralisation is part of a global trend: over the past four decades, more than one hundred countries have implemented administrative decentralisation reforms (Tester 2021). In theory, decentralisation could have either positive or negative effects on public service delivery. Devolving administrative authority to local governments could improve public service delivery if local governments have better information about local needs and resources, or a greater ability to monitor government officials in charge of service delivery. On the other hand, service delivery could worsen if state capacity at the local level is weaker, if local officials are more corrupt, if decentralisation leads to a loss in economies of scale, or if local elites can more easily capture public resources.1 The empirical literature from different countries has found both positive and negative effects of administrative decentralisation.2

In our research (Chaudhary and Iyer 2022), we study the effects of the Panchayati Raj’s administrative decentralisation reforms on human development outcomes, since improving public service provision was one of the main drivers of this reform.

Implementation of Panchayati Raj Acts

India’s Panchayati Raj required all states to establish a three-tier system of local government, comprising of village, intermediate, and district panchayats. In order to achieve administrative decentralisation, 29 functional areas were slated for devolution to these local government bodies, including control over primary and secondary education, public health, water provision, and sanitation. For fiscal decentralisation, states were to establish State Finance Commissions to provide recommendations on revenue-sharing arrangements and grants to these local government institutions. In terms of political decentralisation, all members of these local bodies were to be directly elected by the people every five years, and at least one-third of all local council seats were to be filled by women.

Most states amended or passed new Panchayati Raj Acts immediately in 1993 or 1994 to comply with the constitutional amendment. These Acts called for the decentralisation of public health and education services, among others, to panchayats. Yet, these laws varied in their specificity, with states like Gujarat specifying the powers and duties for each of the three panchayat tiers, while other states used more vague language, simply stating that village panchayats “may” perform various functions related to public health, education, etc. Disappointed with the slow and uneven pace of administrative decentralisation, the central Planning Commission published a report in 2006 asking states to (i) conduct ‘activity mapping’ exercises, which would unbundle each devolved function into smaller units of work and articulate the powers and duties of those smaller units to each panchayat tier, and (ii) pass executive orders to operationalise these activity mapping exercises.

Our findings

To assess the effects of administrative decentralisation, we put together new data on the state-level dates of effective decentralisation of public health functions between 1990 and 2015, based upon a detailed reading of official reports and documents. In particular, we track when states devolved administrative functions to local governments, and when they devolved the functionaries (namely the people tasked with performing or managing the functions, such as public service workers). By 2015, 18 out of 25 major states in our sample had devolved health functions to the local level, but only 13 of these states had also devolved responsibility over functionaries.

We then use a difference-in-difference estimation3 to compare child mortality outcomes for each state in the periods before and after decentralisation, with non-decentralising states serving as a proxy for the trend in outcomes without these reforms.

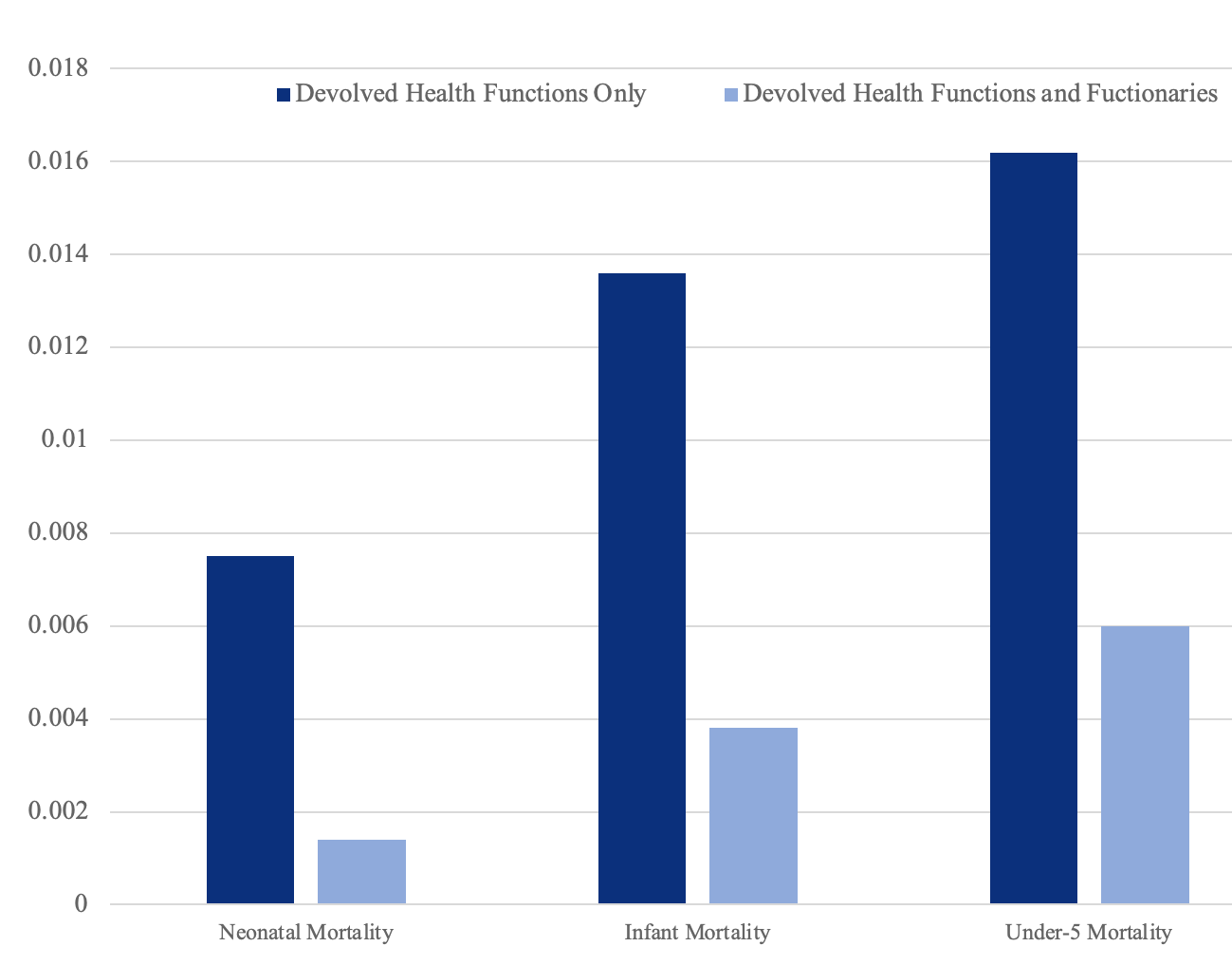

Our analysis yields two main results. First, while there were nationwide improvements in child health outcomes over this period, states that devolved health functions but not functionaries experienced significantly lower gains in neonatal, infant and under-five child mortality compared to states that did not devolve health functions. Figure 1 shows the difference in neonatal, infant and under-five mortality between states that devolved only health functions (dark bars) and those that did not devolve at all – we see that mortality rates are significantly higher among states that devolved only health functions.

Figure 1. Impact of administrative decentralisation on child mortality outcomes

Second, when we perform a similar comparison between states that devolved both functions and functionaries (lighter bars in Figure 1) and states that did not devolve at all, we find that the differences are much smaller and not statistically significant. Somewhat disappointingly, even these states that devolved both functions and functionaries do not show a decline in child mortality rates, which we might expect if public service delivery had improved as a result of devolution. We also find a similar result with funds devolution: states that devolved functions but not the funds experienced a rise in child mortality, while states that devolved both funds and functions did not.

Our results are robust to a range of robustness tests, such as controlling for annual per capita state-level spending on health and political decentralisation, checking for differential pre-trends, and accounting for heterogeneous treatment effects across early and late adopters of devolution.

Conclusion

Overall, our results suggest that devolving responsibility, without concomitant authority over personnel or funding autonomy, is detrimental for human development outcomes.

But what is driving the worsening of outcomes? We find evidence that incomplete devolution results in a decline in the quality of public service provision. We document lower levels of prenatal care and immunisation provision in states that devolved health functions but not functionaries. Importantly, we find similar results for education, which was devolved at the same time as health. Primary school completion rates are lower among states that devolved only functions compared to states that did not devolve either functions or functionaries. States that devolved functions and functionaries did not show any significant improvement in primary school completion, and only some improvement in middle school completion rates.

Notes:

- For more detailed explication of the theoretical channels, see Oates 1972, Smith 1985, Besley and Coate 2003, World Bank, 2004, Bardhan and Mookherjee 2005, 2006a, 2006b.

- For instance, Dahis and Szerman (2021) document improvements in service delivery after decentralisation in Brazil, and Fleche (2021) finds declines in subjective well-being after a centralisation reform in Switzerland, while Malesky et al. (2014) and Cassidy and Velayudhan (2022) find worse service delivery and economic growth in Vietnam and Indonesia respectively following decentralisations.

- Difference-in-difference is a technique to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups that were impacted by a policy with other groups that were not

Further Reading

- Bardhan, Pranab and Dilip Mookherjee (2005), “Decentralizing Anti-poverty Program Delivery in Developing Countries”, Journal of Public Economics, 89: 675-704.

- Bardhan, P and D Mookherjee (2006a), Decentralization and Local Governance in Developing Countries, MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Bardhan, Pranab and Dilip Mookherjee (2006b), “Decentralisation and Accountability in Infrastructure Delivery in Developing Countries”, Economic Journal, 116: 101-127.

- Besley, Timothy and Stephen Coate (2003), “Centralized versus Decentralized Provision of Local Public Goods: A Political Economy Approach”, Journal of Public Economics, 87: 2611-2637.

- Cassidy, T and T Velayudhan (2022), ‘Government Fragmentation and Economic Growth’, Working Paper.

- Chaudhary, L and L Iyer (2022), ‘The Importance of Being Local: Administrative Decentralization and Human Development’, Working Paper.

- Dahis, R and C Szerman (2021), ‘Development via Administrative Redistricting: Evidence from Brazil’, Working Paper.

- Fleche, Sarah (2021), “The Welfare Consequences of Centralization: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in Switzerland”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(4): 1-15.

- Malesky, Edmund, Cuong Viet Nguyen and Anh Tran (2014), “The Impact of Recentralization on Public Services: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis of the Abolition of Elected Councils in Vietnam”, American Political Science Review, 108(1): 144-168.

- Oates, W (1972), Fiscal Federalism, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

- Smith, B (1985), Decentralization: The Territorial Dimension of the State, George Allen & Unwin, London.

- Tester, A (2021), ‘Extending the State: Administrative Decentralization and Democratic Governance Around the World’, PhD thesis.

- World Bank (2004), World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for the Poor, World Bank, Washington, D.C

13 January, 2023

13 January, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.