Off-grid solar power is a potential alternative to grid extension in rural electrification. This column reports results from a recent experiment with an off-grid lighting intervention in Uttar Pradesh. While little evidence of broader socioeconomic changes was found, the study suggests that kerosene subsidies likely hold back the expansion of off-grid solar markets, and that there are many ways in which benefits of off-grid solar power can be enhanced.

While grid extension is the main driver of rural electrification in India today and almost all Indian villages are now electrified, the reality at the habitation and household level is very different. In states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (UP), the electrification of rural households remains a daunting challenge for state governments. Moreover, the 2014-2015 ACCESS survey (Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity – Survey of States) shows that electricity distribution companies struggle to provide rural households with high-quality electricity service (Aklin et al. 2016). Even when households can use grid electricity, be it legally or illegally, the number of hours available is often very low. In Bihar and UP, for example, ACCESS reports only nine hours of electricity on a typical day. Perhaps reflecting the low quality of grid electricity service in many parts of India, an impact evaluation of the Rajiv Gandhi rural electrification scheme found no evidence of economic benefits (Burlig and Preonas 2017).

Considering these facts and the falling costs of off-grid solar power, distributed alternatives to grid extension have drawn a lot of attention in India. In this column, we report results from a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) on the energy access and socioeconomic benefits of an off-grid solar power intervention in rural UP1, and then use the lessons to derive policy insights for the future of rural electrification in India (Aklin et al. 2017). While the RCT did not find evidence of substantial social or economic benefits, we found that India’s kerosene subsidies likely hold back the expansion of off-grid solar markets and that there are many ways in which the benefits of off-grid solar power can be enhanced.

Experimenting with off-grid solar power in UP

We randomly assigned 81 small rural habitations in Barabanki district into a treatment and control group. While no intervention was made in control habitations, households in treatment habitations were offered to subscribe to basic energy access from a small solar microgrid, operated by Mera Gao Power (MGP). In return for a monthly fee of Rs. 100, villagers in previously non-electrified communities could get two LED lights and a mobile phone charger that were powered from the battery-backed solar microgrid. Households could get electricity at night, between sunset and around 11 pm, and installation of a solar microgrid required a minimum demand of 10 households per habitation; a microgrid was installed in 21 habitations.

Over a period of one year, we surveyed 1,281 households three times: before treatment, half a year and one year after treatment. In each survey, we collected information on fuel expenditures, lighting hours, quality of lighting, and broader socioeconomic effects such as household savings or spending, business creation, work time or use of lighting for study. While we found no effects for these socioeconomic outcomes, the energy access effects were sizeable: electrification rates were up by a third and kerosene expenditures decreased by almost Rs. 50 per month - relative to an average total kerosene spending of Rs. 109 per month before the intervention. Importantly though, these reductions were only seen in the private market, while households continued to spend as much money as before on heavily subsidised kerosene from the public distribution system (PDS).

The problem with kerosene subsidies

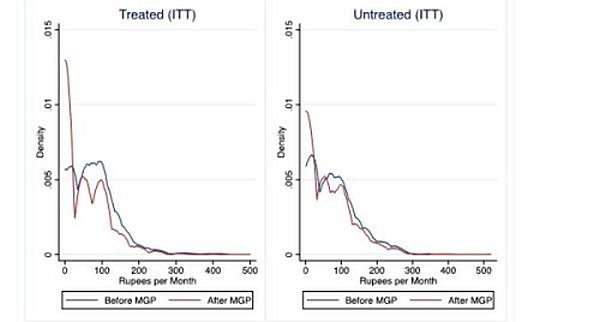

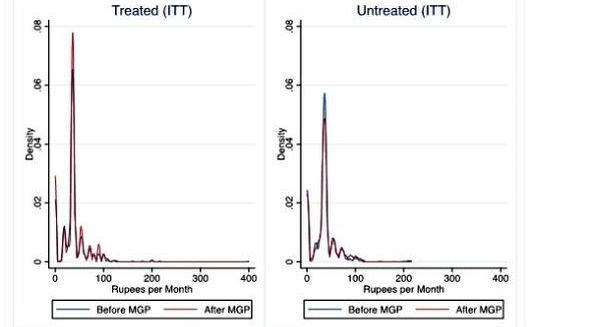

The simplest step forward for Indian policymakers is to replace the subsidy for kerosene with a more efficient policy. Figures 2 and 3 show that in our experiment, the installation of solar microgrids caused a large decrease in kerosene from the private market but did not reduce purchases of subsidised kerosene from the PDS. Even households that used solar lighting continued to purchase heavily subsidised kerosene as before. No wonder, then, that the overall adoption rate was only 14% among households in the treatment group.

Figure 2. Monthly household spending on kerosene in the private (black) market

Note: The figure on the left includes households in the intent-to-treat group (households targeted by MGP) and those on the right are in the control group (households not targeted by MGP). The blue line shows spending before the MGP intervention, and the red line shows spending after it.

Note: The figure on the left includes households in the intent-to-treat group (households targeted by MGP) and those on the right are in the control group (households not targeted by MGP). The blue line shows spending before the MGP intervention, and the red line shows spending after it. Figure 3. Monthly household spending on kerosene from PDS

Note: The figure on the left includes households in the intent-to-treat group (households targeted by MGP) and those on the right are in the control group (households not targeted by MGP). The blue line shows spending before the MGP intervention, and the red line shows spending after it.

Note: The figure on the left includes households in the intent-to-treat group (households targeted by MGP) and those on the right are in the control group (households not targeted by MGP). The blue line shows spending before the MGP intervention, and the red line shows spending after it. There are at least two policies that could enhance the competitiveness of off-grid solar lighting and help rural India gain access to better, brighter lighting. The first is a solar voucher. Households could choose between a standard kerosene subsidy and a voucher that they can use to purchase solar products from a competitive market. Under this model, the voucher would allow households to replace traditional kerosene lighting with off-grid solar power. Moreover, the voucher could create competition among off-grid solar technologies, as it could be used to buy the households’ preferred products among many alternatives. Finally, the distribution of solar vouchers would boost demand for off-grid lighting solutions and thus unlock both learning by doing and economies of scale.

Alternatively, even a direct cash transfer would reduce the bias against off-grid solar products. If households would receive their kerosene subsidy in cash, perhaps through India’s Aadhaar2 system, households would not be forced to buy kerosene to benefit from the policy. Some households might continue buying kerosene, others would invest in solar lighting, and yet others would find completely different uses for their money. Unlike the solar voucher, this policy would not directly expand demand for off-grid solar technologies, but it would still remove the artificial advantage that kerosene has thanks to generous subsidies.

Enhancing the impact of off-grid solar power

Off-grid solar power did not produce socioeconomic benefits in our study, but there are several ways in which such benefits might be enhanced. One is simple: install larger systems that produce more energy for the people. If households could use technologies such as fans or refrigerators, the opportunities for economic gain could multiply. The downside of larger systems is that they are more expensive for the consumers, and thus it is important to compare the potentially larger benefits against the potentially larger costs.

Another approach would emphasise complementary interventions. The lack of electricity is not the only obstacle to economic growth in rural India, and rural households without electricity access often have to grapple with other challenges as well, ranging from low-quality schools to a lack of proper roads and limited access to credit for livelihood creation. Combining innovative off-grid solutions with other interventions could relax multiple constraints on growth at the same time, with potential for large returns.

For better off-grid lighting policy, it is important to continue experimentation and rigourous impact assessment based on randomisation. Ending energy poverty is essential for sustainable human development in India and elsewhere, and success in this effort requires evidence-based policy and business models. Our conclusions should not be seen as the final word on the issue, but as a call for further research on the potential, pitfalls, and design of off-grid lighting interventions.

Notes:

- The study began with a baseline survey in February 2014 and finished with an endline survey in October 2015.

- Aadhaar or Unique Identification number (UID) is a 12-digit individual identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) on behalf of the Government of India. It captures the biometric identity – 10 fingerprints, iris and photograph – of every resident, and serves as a proof of identity and address anywhere in India.

Further Reading

- Aklin, Michaël; Chao-yo Cheng, Johannes Urpelainen, Karthik Ganesan and Abhishek Jain (2016), "Factors affecting household satisfaction with electricity supply in rural India", Nature Energy, 1, Article number 16170.

- Aklin, Michaël, Patrick Bayer, SP Harish and Johannes Urpelainen (2017), "Does basic energy access generate socioeconomic benefits? A field experiment with off-grid solar power in India", Science Advances, 3(5):1-8.

- Burlig, F and L Preonas (2016), ‘Out of the Darkness and Into the Light? Development Effects of Rural Electrification’, Working Paper 268, Energy Institute at Haas, University of California, Berkeley.

17 July, 2017

17 July, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.