Following his last piece, which put forth a Governance Matrix that could be used to assess a government system’s readiness to drive outcomes, Gaurav Goel suggests five principles, or panchsutras, which are critical for the success of a governance transformation. Using the example of the Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen, he shows that these principles are key to not only spurring the system into action, but also maintaining momentum towards achieving a goal, and ensuring long-term sustainability of the transformation

An oft cited aphorism about Indian governance is that the government knows “what needs to be done, all they need support with is the how”. In a complex system like a national, state, or local government, the difficulties associated with the ‘how’ are manifold. It is no wonder then, that while many commendable initiatives are undertaken by governments to improve developmental outcomes for citizens (in the form of various schemes, programmes and missions), not all fare well. Most of the analysis around the failure of these initiatives tends to be retrospective, delving into everything that should have been considered but wasn’t.

What is a governance transformation?

However, what if the question was flipped to offer a more constructive view: what can be done to ensure a higher probability of an initiative, or a ‘governance transformation’ succeeding? For the purpose of this article, we define governance transformation as any government programme that involves a set of interventions designed and implemented over a period of time to improve citizens’ quality of life. Governance transformations could be in any domain, and are typically characterised by i) the long-term (often multi-year) nature of the programme, requiring sustained effort; ii) a set of interventions to achieve the goal, as opposed to a single, point intervention; iii) effort that is beyond the business-as-usual working of the government; and iv) implementation at scale.

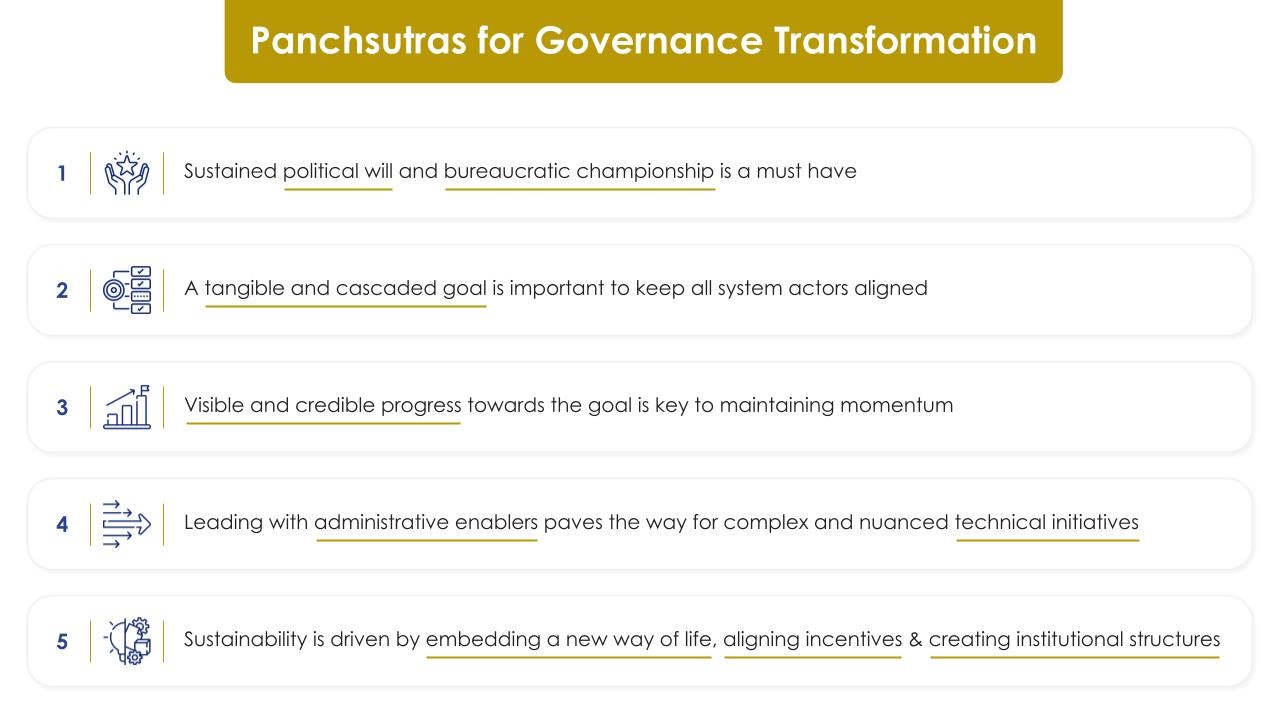

This article lays out the five key principles, or panchsutras, for carrying out a successful governance transformation at the national, state or local level.1 Using the panchsutras, practitioners engaging with or in government can be more deliberate in the way they design or implement governance transformations, and ensure they have the maximum chance of succeeding. To make the explanation of the principles illustrative, the article uses the example of Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen, or SBM(G). The programme was launched in 2014 as a national campaign to eliminate “open defecation in rural areas during the period 2014 to 2019”. In the five-year period, SBM(G)’s target was largely achieved, with rural India being declared open-defecation free. While the jury is still out on the extent of open defecation prevalence in some parts of the country, SBM(G) is still an example of a fairly successful governance transformation

Panchsutras for Governance Transformation

i) Sustained political will and bureaucratic championship is a must have: For the success of a governance transformation, it is important for the elected head of the government to demonstrate political will for the goal. Political will can be demonstrated by bringing in the best suited bureaucrat to lead said governance transformation, since it is the bureaucrat who, acting like a CEO, steers the system towards delivery. The tranformation being a prioity of the head of the government reduces the chances of frequent transfers of key bureaucrats, and ensures that suitable replacments will be found even if transfers do take place. Political will and bureacratic championship together ensure the availability of necessary resources for the transformation, particularly in the form of budgets. Political will is further manifested by rallying public support for the goal through speeches, events, media, advertisements and so on. For governance transformations that affect deep-rooted vested interests, political will becomes all the more critical to resist any potential pushback from the ecosystem. It is also important to note that since governance transformations typically take a few years, the best time to initiate them is at the beginning of an elected government’s term or at least a few years away from the next elections.

In the case of SBM(G), strong political will to reform the sanitation landscape in rural areas was communicated and demonstrated by the Prime Minister time and again. The government brought in Parameswaran Iyer, a technocrat with expertise on sanitation as well as experience in the civil services, to lead SBM(G). The programme was backed by a substantial budget of over Rs. 1,300 billion, shared between the Centre and states across five years, in addition to investments from the private sector and philanthropies. Between 2014 and 2019, “The topic of Swachh Bharat featured [around] 40 times over the years on Mann ki Baat, a key touchpoint between the PMO and the public”. The strong push from the political leadership, particularly the Prime Minister himself meant that “a range of government ministries, private sector organisations, the philanthropic ecosystem, civil society, and the media entertainment sector participated to bring sanitation messaging and awareness to citizens at significant scale” (Dalberg, 2019). The constant nudge from the top meant that this became a priority for every district collector in the country, and ensured that all government functionaries gave their best to achieve targets and make the programme successful.

Working backwards from the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi on 2 October, 2019, the programme was launched right after the 2014 elections, thereby giving all system actors the required runway to achieve the goals.

ii) A tangible and cascaded goal is important to keep all system actors aligned: To drive transformation through a large government system, it is important to direct the system’s energy towards a common goal. All actors in such large systems are usually preoccupied with routine responsibilities in an attempt to keep the system running as is. Further, large systems also have significant inertia or resistance to change. A common goal, which the leadership signals to be critical, helps in decluttering and making all system actors aware of a singular objective. However, an announcement by the leadership alone does not activate every stakeholder at various The goal has to be tangible – that is, it has to be relevant as well as easy to understand, communicate and measure. It also has to be cascaded across administrative levels (state, district, block, panchayat), and the goal for smaller administrative units should roll up to the larger goal. Tangible and cascaded goals ensure the efforts of all stakeholders are targetted and coordinated.

In SBM(G), becoming 100% open defecation free (ODF) was set as a tangible goal. This goal could also be easily cascaded at different levels of the administration – as the campaign matured, the focus shifted from making gram panchayats ODF, to declaring districts and ultimately entire states as ODF.

iii) Visible and credible progress towards the goal is key to maintaining momentum: A large system, forced to break its inertia and spurred into action, is more likely to fall back into its business-as-usual mode of working. It is important to demonstrate progress that can be claimed as wins over the course of the transformation in order to maintain momentum and remain energised to attain ambitious goals over a long period of time. For government officials and field functionaries, demonstrating progress in the initial phase is key to overcoming the scepticism that prevails among system actors with respect to complex governance transformations, and to make them believe that change is indeed possible. However, it is also critical that the progress is credible, either based on reliable system-generated metrics or verified independently, to reinforce the confidence of system actors as well as citizens.

SBM(G) initially focused on a set of high-performing districts and supported them in their efforts to become ODF. Once that milestone was achieved, a core group of 60 high-performing District Magistrates (DMs), called Super 60 DMs, was created to inspire others. As another way to incentivise better performance, a group of 25 well-performing DMs was given an opportunity to meet Sachin Tendulkar, a highly-celebrated Indian cricketer. This immediately caught the attention of other DMs, each now motivated to get their district over the line as well. These and other initiatives served both as a demonstration, as well as motivation, for other districts to follow suit.

At the district level, to credibly verify that toilets were actually being built and used, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation brought in the Quality Council of India (QCI), an autonomous accreditation body. In addition to QCI, independent verification was also done by the National Sample Survey Organisation, and the National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey (supported by the World Bank) through on-ground surveys to verify ODF status in states and Union Territories.

iv) Leading with administrative enablers paves the way for complex and nuanced technical initiatives: It is imperative that the system which is meant to take on this responsibility has basic capabilities in place, in terms of people, processes and funding and These administrative enablers create the ‘plumbing’ required to implement complex technical (domain-specific) initiatives that are necessary for a governance transformation. Administrative enablers could be targetted to ensure availability of sufficient frontline staff through creation of a new cadre, recruitment or transfers (people), or having appropriate communication and reporting mechanisms amongst system actors (process), or unlocking timely and adequate availability of funds required to seamlessly drive operations (funding), to name a few. Without the necessary plumbing in the form of administrative enablers, most technical initiatives that get pushed through the system are likely to leak along the way and not manifest on the ground in the intended manner.

In the context of SBM(G), on the people front, a Swachh Bharat Mission Director was appointed at the state level. In collaboration with Tata Trusts, the government also created the Zila Swachh Bharat Prerak programme, which recruited motivated and well-qualified youth to implement the Mission at the district level. A cadre of swachhagrahis, who could use their understanding of grassroots context to effectively mobilise the community, was created at the village level.

On the process front, new modes of communication were established to ensure the seamless flow of information within the government system. The Ministry set up an online review and monitoring system, and an Integrated Management Information System, which captured granular data at the household-level on the sanitation facilities of all gram panchayats. ODF war rooms were also established at the district level to keep track of progress on a regular basis, including through weekly reviews by the District Collector. Joint annual reviews with states and districts were also undertaken.

The massive funding mobilised for SBM(G) was also available seamlessly when needed. Based on evidence of progress, funding was made available in a transparent and efficient manner. The Ministry would transfer funds to the state government, which would transfer the same to the state’s Swachch Bharat Mission within 15 days. They in turn had 15 days to allocate funds to District Swachch Bharat Missions. Any delay in this process invited a penalty.

v) Sustainability is driven by embedding a new way of life, aligning incentives and creating institutional structures: A governance transformation aims to change the status quo. While driving the transformation, it is also important to think through measures and institutional structures that can make the transformation irreversible. Sustainability can be driven by i) a new way of life getting embedded, often enabled by technology, making sliding back to old ways difficult; ii) aligning incentives of system actors and beneficiaries, thereby creating a self-sustaining synergy in the ecosystem; and iii) creating or strengthening institutional structures to enable continuity in the improved, new way of life.

Admittedly, in the context of SBM(G), it is still too early to claim that sustainability has been ensured. Still, the programme has put in place mechanisms to get there. First, SBM(G) used a strong information, education and communication (IEC) campaign to make using the toilet a habit. A big push towards this was made through the Darwaza Band campaign, which focused on “toilet use and freedom from open defecation across the country's villages”. Celebrities who could influence behavioural change were roped in for the campaign. To align incentives, Rs. 12,000 per toilet was provided at the household level to promote toilet construction. System actors could thus see that achieving the goal was linked with a tangible financial incentive. While effective monitoring systems were set up in a standardised manner across the states, the ministry ensured ample flexibility for states to tweak the campaign, have their own missions and define delivery mechanisms to suit their cultural contexts. There was a strong push towards creating robust institutions at the state level and below, which could take the mission forward in a decentralised manner.

Conclusion

The first panchsutra (political will) is a prerequisite for a governance transformation, and is required throughout the course of reform till the goal is achieved. The second (goal-setting) and third (visible progress) play a critical role in spurring the entire system into action and maintaining momentum towards a common goal across administrative levels. These also contribute towards sustaining political will over the period of the transformation. While momentum gets built through short-term wins, it is important to be cognisant of the fourth panchsutra (leading with administrative enablers) so that the system becomes ready to take on complex technical reforms in the long run that are necessary for a governance transformation, and will ultimately lead to sustainable outcomes. The fifth panchsutra (sustainability) is necessary to embed new habits and ways of working in the system, incentivise system actors and beneficiaries to not revert to old habits, and create or strengthen institutional structures that can maintain the new status quo.

Overall, even if one of the five panchsutras is missing, it puts the success of the governance transformation at risk. These panchsutras can be useful for practitioners in, or engaging with, government to design and implement transformation programmes more deliberately such that they have the maximum chance of achieving their objective.

Note:

- These learnings have been accumulated by Samagra, a mission-driven governance consulting firm, from a decade of experience of working with governments at the centre, states and districts on varied domains such as education, health, employment, skilling and agriculture.

Further Reading

- Dalberg (2019), ‘An assessment of the reach and value of IEC activities under Swachh Bharat Mission (Grameen)’, Whitepaper.

09 December, 2022

09 December, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.