India has had a long-standing policy of affirmative action to address deep-rooted caste inequities and discrimination. This article compares successive age cohorts of three broad social groups – Scheduled Castes and Tribes, Other Backward Classes, and upper castes among the Hindu population – and provides the first disaggregated picture of the evolution of inter-caste disparities in India in terms of key indicators such as education and employment.

The hierarchical nature of the Indian caste system is simultaneously its most commonly known characteristic and the most disputed one. Some degree of hierarchy among castes – implicitly conveyed in the terms “upper” and “lower” castes – seems to be conventional wisdom. However, a large volume of scholarly work and journalistic commentary is devoted to questioning whether the old hierarchies are valid any more, as castes that were previously low in the hierarchy are now seen as dominant castes, replacing the older, mainly upper-caste elite.

This change is presumed to have taken place during the time the Indian economy became increasingly market-oriented and globally integrated. Additionally, the representation of lower castes in elected positions increased since the 1990s. Thus, there are good reasons to expect that the economic position of lower castes would have improved and that gaps in material indicators between caste groups would have declined, at least since the 1990s.

India has had a long-standing policy of affirmative action (AA) to address deep-rooted caste inequities and discrimination. Carrying forward localised instances of caste-based quotas for “depressed classes” from parts of British-ruled territories and independently administered princely states, quotas were constitutionally mandated at independence for the most socio-economically disadvantaged sections of society – the former untouchables or the Scheduled Castes (SC), and a group of tribals or indigenous peoples (Scheduled Tribes, or ST). Quotas for SC-ST stand at 22.5%1 of all government jobs, seats in higher educational institutions, and elected positions.

These quotas were further extended at the central government level to an intermediate group of castes and communities called the “Other Backward Classes” (OBCs). Job quotas for OBCs (additional 27%), who comprise around 44% of the population, started in 1993, and educational quotas in 20062.

What has been the result of these developments? Have traditional caste hierarchies either flattened or reversed over the last six decades, and if yes, in what dimensions? Have quotas been effective, that is, have they delivered on target? Evaluating the first-order effects for SC-ST quotas is difficult, as localised quotas started in the second decade of the 20th century, and continued post-independence. Thus, our assessment of the effects of OBC quotas provides an important piece of evidence on the efficacy of AA.

Key Findings: Education

We use data from the National Sample Survey (NSS) Employment-Unemployment Surveys (EUS) for 1999-2000 and 2011-12 on individuals between 16 and 65. We focus on the subsample of Hindus, who are 82% of all individuals, in order to examine the gaps between the lower and upper castes. More precisely, we use the relevant administrative categories – SC/STs, OBCs, and Others (a residual category comprising Hindu upper-castes when only the Hindu population is considered). Our emphasis is on national-level estimates to provide a macro picture on the evolution of caste disparities, but we also examine the regional picture. We slice NSS data into 10-year age cohorts, and compute both absolute and relative gaps in key indicators such as educational attainment, occupation, wages, household expenditure, across caste groups and cohorts to check for convergence over time.

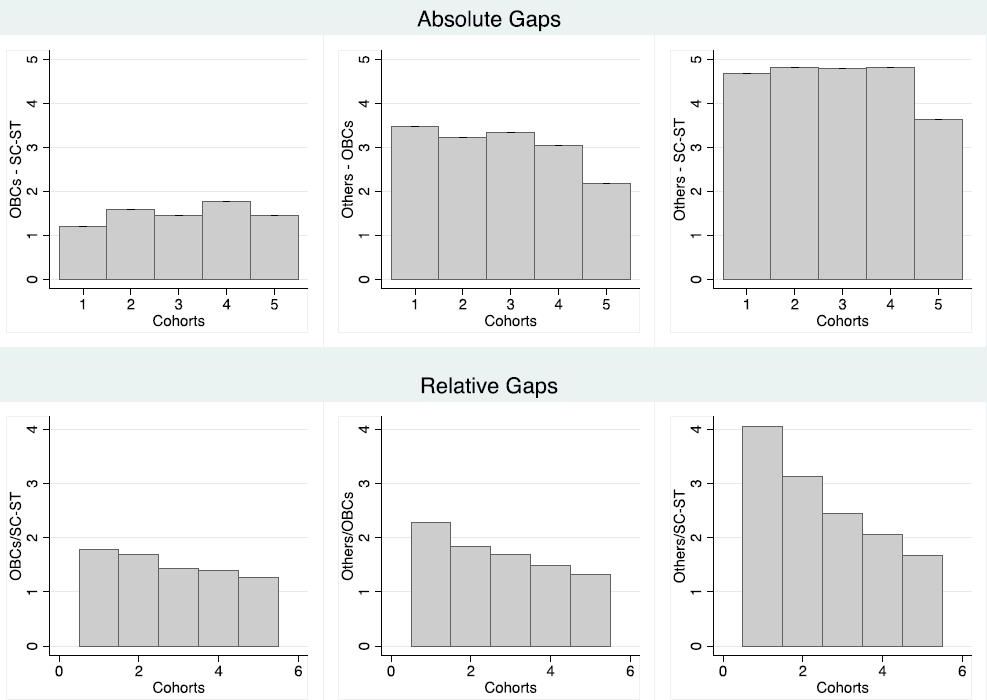

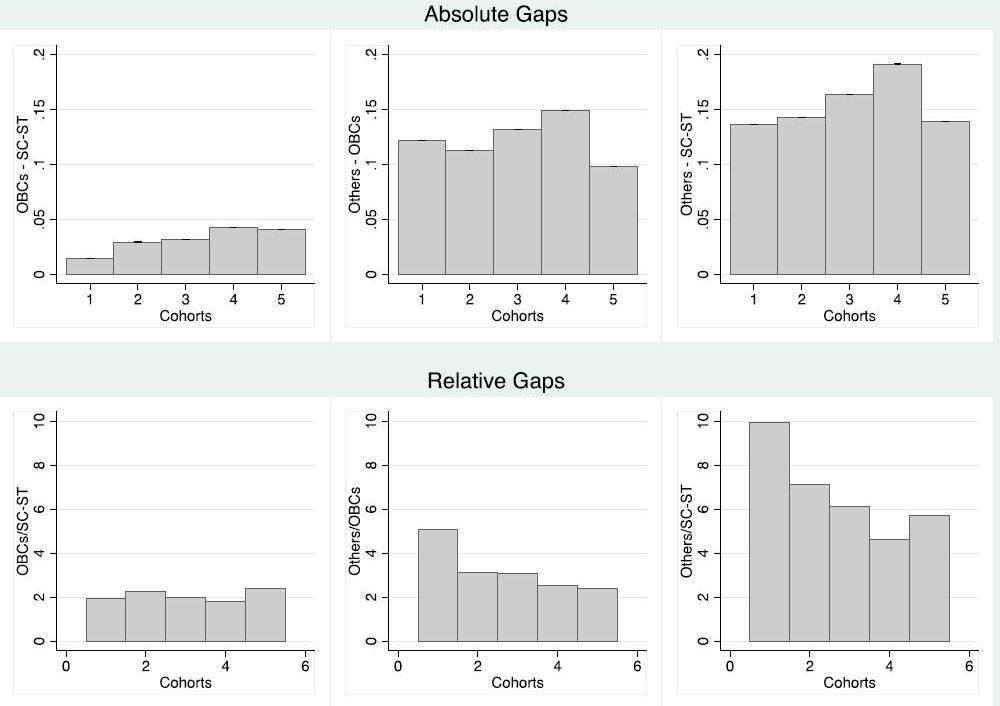

Our analysis shows that for the lowest categories of education – literacy and completion of primary schooling – both absolute and relative gaps have reduced between caste groups. For higher categories of education, as well as for the composite indicator of years of schooling, the answer to whether caste gaps have narrowed or widened depends on which gap we look at. Whereas absolute gaps between SC-STs (OBCs) and upper castes in years of education have remained static, relative gaps have decreased.

Figure 1. Evolution of absolute and relative gaps between caste groups: Average years of education

Figure 2. Evolution of absolute and relative gaps between caste groups: Graduate degree and above

Now, does a decline in relative gaps in years of education mean that gaps in wages have reduced as well? For that we need to examine how the labour market rewards years of education. Evidence shows that for the first several years of schooling the marginal rewards are nil, then increase till grade 12, and decline thereafter. In our specific context, this implies that although the relative gaps in years of education have declined, there has been a further increase in the labour market rewards to schooling in favour of the upper castes. Therefore, based both on absolute gaps and the specific level of relative gaps, we find that except for the lowest categories of educational attainment, upper-caste Hindus have further reinforced their educational advantage in the last five to six decades.

Occupation and wages

We divide workers into three broad occupational categories: agricultural, blue-collar, and white-collar. Examining caste differences in occupational distribution for the most prestigious category of white-collar jobs, we find little or no change in the extent of caste gaps, using either notion of convergence (absolute or relative gaps), indicating that hierarchies have remained largely static over the past five decades.

The evolution of the log of real daily wage gaps between 1999-2000 and 2011-12 shows convergence (narrowing of gaps) between SC-STs (OBCs) and upper caste Hindus, when we consider the wage earners below the log median daily wage. For wage earners above the log median daily wage, we find neither convergence nor divergence between the OBCs and the upper-caste Hindus. But SC-STs above the median wage have fallen further behind upper-caste Hindus.

The findings on the evolution of wages mirror that of the education and occupational analysis. As caste gaps have closed in lower categories of education, wage gaps have been closing for workers earning below the median wage. As caste gaps in higher categories of education have increased or remained the same, wage gaps in the upper half of the wage distribution and in access to white-collar jobs have increased.

Decomposing the wage gap, we also find an increase in the unexplained part of the wage gap between upper castes on the one hand, and SC-STs and OBCs on the other. One interpretation could be an increase in labour market discrimination against lower ranked castes, whereas another explanation could be an increase in labour market returns to skills more present in the ‘Others’ group.

Effect of OBC quotas

We find that the provision of quotas increases the share of OBCs in government jobs by around four percentage points. Government jobs require candidates to have at least completed secondary school education (Class X) in order to be eligible for even the low-paying jobs. Consistent with this reasoning of incentives presented by job quotas, we find that AA resulted in an increase in the probability of completing secondary education by 5 percentage points for the youngest cohort of OBCs.

Conclusion

Our first major contribution is that we provide a detailed and nuanced assessment of the evolution of group disparities in a large, fast-growing, and globalising economy. The other major comparable study (Hnatkovska et al. 2012), undertakes a two-way comparison between SC-STs and non-SC-ST. They find evidence of convergence across a range of indicators between 1983 and 2005. However, their evidence is not able to isolate the trajectory of SC-STs relative to OBCs and Hindu upper-castes separately. Given that the bulk of the flux in caste hierarchies lies in the middle, we believe that in order to gauge the contours of change, we need to examine the three categories separately, at the very least, if not at an even more disaggregated level.

Moreover, because other studies include Muslims, one of the most socially disadvantaged groups in India in the non-SC-ST group their results tend to overstate the extent of convergence between the caste groups. We rectify this by considering OBCs as a separate group, and by focusing on caste gaps within the Hindus. Second, we present the evolution on both absolute as well as relative gaps. Our estimates highlight the importance both of separating the OBCs from the upper castes, as well as accounting for absolute gaps, in addition to relative gaps.

Our analysis highlights the continued relevance of caste in understanding contemporary inequalities in Indian society, providing a rigorous empirical foundation to the claim that “caste is not an archaic ritual system, but a dynamic aspect of modern economies” (Mosse 2018). The fact that caste disparities have either remained static or widened in higher education categories and in prestigious occupations, even in the context of the positive effects of AA, indicates that disparities might have been larger in the absence of AA. It also suggests that multifaceted policy interventions that include, but go beyond, AA would be required to eliminate deep-rooted social hierarchies.

Notes:

- This is roughly the combined population share of the two groups. Additionally, there is 33% quota for women in rural and urban local bodies.

- Despite being designated as beneficiaries of AA, OBCs are not counted as a separate category in the decennial Indian censuses; all estimates about the size of the OBC population are based on large-scale sample surveys. This is perhaps the only instance in the world where a group is designated as a beneficiary of a public policy, without the government having a clear idea about the size of the beneficiary population.

Further Reading

- Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2019), “Traditional Hierarchies and Affirmative Action in a Globalizing Economy: Evidence from India”, World Development, 118:63-78.

- Hnatkovska, Viktoria, Amartya Lahiri, and Sourabh Paul (2012), “Castes and labor mobility”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(2), 274–307. Available at: http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/alahiri/AEJ_published.pdf

- Mosse, David (2018), “Caste and development: Contemporary perspectives on a structure of discrimination and advantage”, World Development, 110, 422–436.

21 June, 2019

21 June, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.