In this study, Sekhri and Hossain use district-level data to find empirical evidence that groundwater scarcity results in an increase in sexual violence against women. They argue that in households without access to clean drinking water, women often have to walk far from home to collect water, making them more vulnerable to sexual violence. Since they establish that water shortages increase the risk faced by women water collectors, it makes the case for increased investment in water infrastructure.

Women and children are responsible for collecting water to meet households’ needs in many parts of the developing world (UNICEF, 2016). For instance, in Somalia, 71% of households do not have access to clean drinking water. Of these, women are the water carriers in 66.4% of households (Sorensen et al. 2011). Similarly, in Malawi 87.2 %, and in Bangladesh 88.8% of water carriers are women (Sorensen et al. 2011), whereas the corresponding number for India is 64% (authors’ calculation using IHDS data). According to one UNICEF estimate, women and girls around the world collectively spend around 200 million hours daily collecting water (UNICEF, 2016). Women have to walk far away from their houses or even villages to collect water. This increases the exposure and time spent by women outside their houses or safe areas, and hence makes them more vulnerable to sexual violence.

Picture credit: Author’s own

In our paper (Sekhri and Hossain 2023), we show that when groundwater access becomes relatively scarce, women from households reliant on groundwater to meet drinking needs spend more time fetching water. We argue that this lack of access to safe drinking water makes women and girls more vulnerable to violent sexual crimes and increases the incidence of rape.

Data and methodology

We use data on crimes against women from the National Crimes Records Bureau (NCRB), with police FIRs forming the basis of the district-level crime data. We construct a panel at the district-year level from 2002-2007. In order to measure the scarcity, we use water-table data collected for the observation wells across the country.

For each district, we first calculate a long-term mean using data from 1971 to 2001. Then, we use the deviations of water-table depth in each year from 2002 to 2007. This deviation is used to measure negative or positive shocks in water supply – if groundwater moves closer to the surface relative to long-term mean, the district experiences a positive shock and when it moves deeper, it experiences a negative shock. We condition our shock measures on rainfall shocks in each year (calculated in a similar manner, using long-term mean of rainfall for a district), any features of the districts that are time invariant but might affect water-tables and women’s safety (such as geographical location), and year specific conditions experienced by all districts which may influence both water depth and women’s safety (such as national policies). We also account for district-specific time trends to net out characteristics of districts that may vary over time and bias our estimates. In addition, we conduct a wide array of robustness tests including controlling for population, gender ratio, climatic variables like temperature, electrification, measures of poverty, specification, allowing for spatial correlation in water shocks, and multiple hypothesis testing.

Our findings

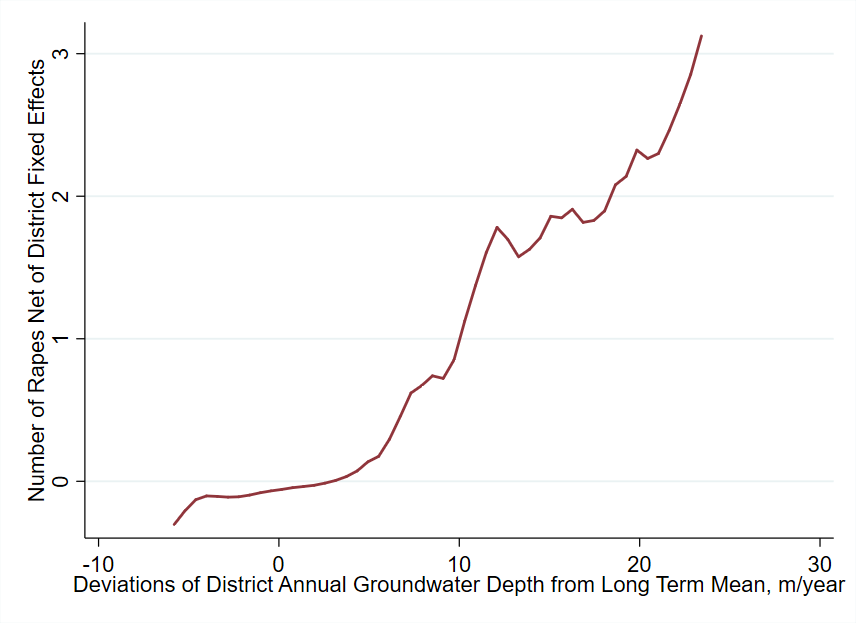

We consistently find a strong effect of water scarcity (measured by negative shocks) on rape (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of negative water shocks on incidence of rape

Note: Numbers on the x-axis represent the deviation of groundwater from its long-term mean. A positive number indicates a falling water table (negative water shock) and a negative number means groundwater has moved closer to the surface relative to long term mean (positive water shock)

Subsequently, we use the household panel data from two rounds of the India Human Development Survey (2005 and 2012) to shed light on the driving mechanism. We find that groundwater’s scarcity leads to women walking farther from their houses, especially in households reliant on groundwater for drinking water needs. We then show that the incidence of rape increases when women from groundwater-reliant households face negative shocks and walk farther from their homes.

Picture credit: Author’s own

One caveat of our study is that we used data on officially reported sexual violence, which is often underreported in India due to cultural norms of associating rape with shame and dishonour. If groundwater shocks affect the reporting pattern, our results would be biased. To test whether groundwater shocks affect reporting pattern, we use the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey and find no changes in case reporting due to negative shocks. Our analysis indicates that other crimes against women did not respond to shocks in a consistent manner, further suggesting that our results are not driven by variations in reporting patterns.

Our data and findings are also inconsistent with a number of alternative explanations other than an increase in exposure as the mechanism behind our main findings. One key concern was that increased poverty may be driving the increased incidence of rape in our results, but we control for measures of poverty and find no changes in our results. We also conduct a placebo test – if poverty was driving the results, then in areas where a poverty-offsetting safety net programme was implemented, we would have found reduced effects. However, we do not observe this pattern, suggesting that poverty may not be the driver of our results. We use the phased roll-out of MNREGA, a rural employment guarantee scheme with reservations for women, over this period to test this hypothesis. We find no difference in the effects of shocks in districts with and without this programme. This further suggests that poverty is not the main driver of effects on rape.

Another related concern might be that if unemployment of men goes up and they have more time, risks of rape for women go up. To see whether this is the case, we control for men’s employment rates. Again, our results do not change. If violence was an effect of frustration vented by men facing economic hardship, stress would ideally increase all types of violence, especially domestic violence. If frustration from unemployment was the reason provoked men to commit crimes against women, we would increase all types of violence, especially domestic violence. However, we do not find evidence of any effects on domestic violence.

Since water scarcity can reduce women’s welfare and increase their risk of experiencing violence, our paper has important policy implications. Investments in water infrastructure, including community wells, distribution channels and taps might mitigate this risk and reduce women’s vulnerability.

Further Reading

- Sekhri, Sheetal and Md Amzad Hossain (2023), “Water in Scarcity, Women in Peril”, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, forthcoming.

- Sorenson, Susan B, Christiaan Morssink and Paola Abril Campos (2011), “Safe access to safe water in low income countries: Water fetching in current times”, Social Science & Medicine, 72(9): 1522-1526.

- UNICEF (2016), ‘Collecting water is often a colossal waste of time for women and girls’, Press Release, 29 August.

18 May, 2023

18 May, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.