The Covid-19 pandemic brought with it the dual crises of public health and the economy, particularly in low-income settings with limited formal safety nets. Based on a large-scale phone survey conducted across six Indian states, this article finds that stricter containment measures, while potentially crucial to check the spread of the virus, are associated with worse mental health among women and higher food insecurity.

The Covid-19 pandemic represents a twin – public health and economic – shock, with devastating effects, particularly in low-income settings where substitutes for in-person transactions are scarce, State capacity for aid and insurance are limited, and supply chains are less resilient (Egger et al. 2021).

Women may be especially vulnerable in these settings given discriminatory gender norms and low availability of mental health services. To examine how women fare, we conduct a large-scale phone survey across six states in rural north India (Bau et al. 2021). India's highly spatially variant containment policies allow us to study how the pandemic and its containment policies affected nutrition, incomes, and female mental health.

While lockdowns may be crucial to stem the spread of Covid-19, we find that when not combined with adequate social safety nets, they can generate economic and mental distress.

Emerging evidence suggests that rural India suffered significant disruptions to food supply chains and reductions in economic livelihoods, perhaps affecting the physical and mental well-being of vulnerable populations (Afridi et al. 2020, Singh and Kumar 2021). Yet, without a systematic measurement of these outcomes for at-risk rural populations across different regions of the country, the extent of this crisis, and its relationship with containment policies, is difficult to quantify.

Phone survey

Building off a sample of 4,799 households that were interviewed in-person in Fall 20191, we conducted a timely re-survey of 32% of the sample via phone in August 2020 with IDInsight, at the height of the first Covid-19 wave in India, when the country had between 50,000 and 70,000 new cases per day. This setup not only gave us measures of the pre-pandemic baseline characteristics but also allowed surveyors – who had already developed relationships with these households – to inquire about women's mental well-being. We conduct the phone survey in 20 districts across six states: Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Households participated in a 20-30-minute survey, during which we survey both the household head and either the female head or another available female respondent2.

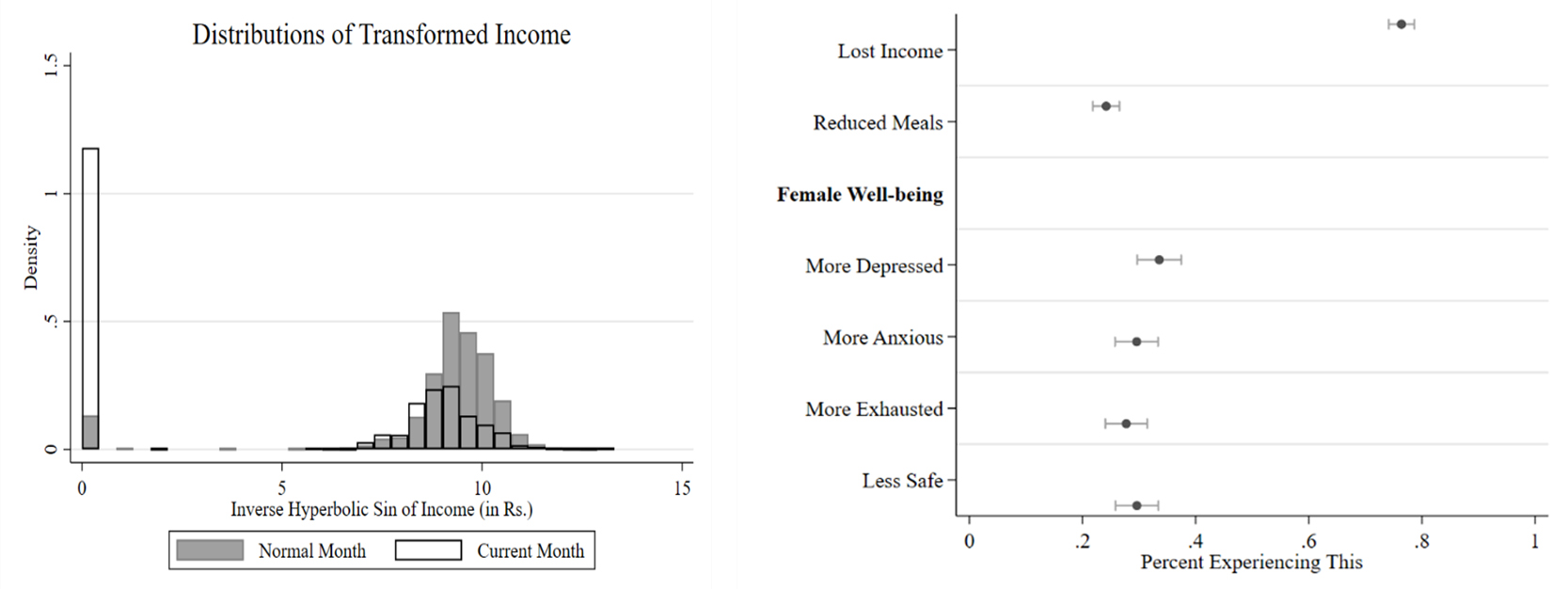

We find that the pandemic is associated with drastic income losses and increased food insecurity, as well as declines in female mental health and well-being. On average, the household head's reported monthly income fell from Rs. 8,625 in a normal month to Rs. 3,584 during Covid-19 – a decline of about 50% (Figure 1, left panel). The right panel shows that 76% of respondents report reduced income for themselves, and 24% report reduced meals for at least one household member.

Further, roughly 30% of the female respondents report that their feelings of depression, exhaustion, anxiety, and perception of safety worsened over the course of the pandemic.

Figure 1. Impact of the Covid-19 shock on income and female well-being

Notes: (i) The left panel shows the distribution of household head's self-reported income in the current month (Covid-19 period) and a non-Covid-19 month, in rupees. (ii) The right panel reports the percentage of households reporting reduced income, reduced meals, and worse female well-being for different measures.

Assessing the impact of containment measures

Identifying the impact of containment measures is generally challenging, as containment is not randomly assigned, and is often mandated at the state or national level3. We leverage the fact that containment exposure was highly geographically variant, in our setting. While India initially imposed a nationwide lockdown in March 2020 in response to the pandemic, from June 2020 onward, it had a patchwork of containment zones in which lockdown measures were imposed. These zones were determined by district or town authorities based on public health considerations, and their size could be as small as one apartment building or a one-kilometre radius. This mosaic of policies within relatively small geographic areas provides us with an opportunity to use meaningful variation in lockdown policies to assess the relationship of containment, with mental health and other measures of well-being.

Two pieces of evidence suggest that the association between containment and outcomes may capture the direct effects of containment, even though containment policies were not randomly assigned to geographic units. First, living in an area with a higher prevalence of lockdowns is not systematically associated with pre-Covid socioeconomic measures, either for outcomes collected from our own sample prior to the pandemic or for district-level measures of food intake in NFHS-4. Second, the inclusion of district-level cumulative measures of case and death rates in the analysis allows us to compare two areas with the same Covid-19 incidence but different containment policies, and this does not change the estimates.

Female well-being, socioeconomic and nutritional outcomes

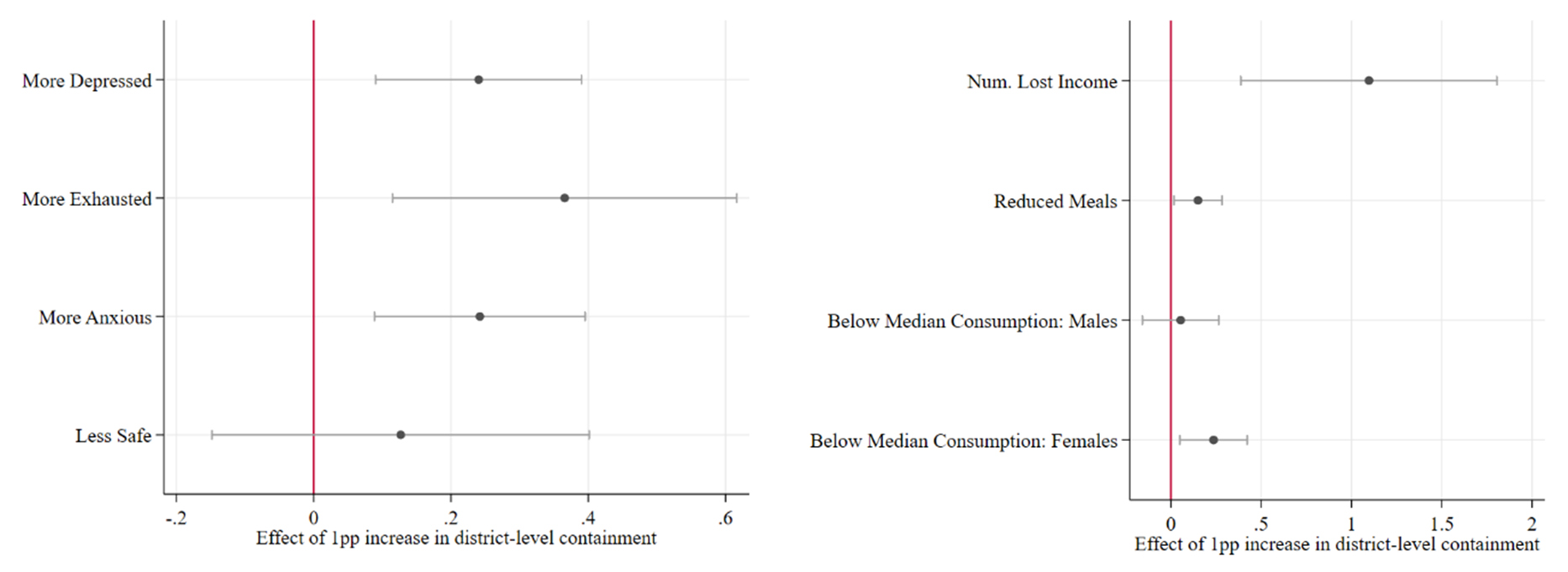

More stringent containment is associated with a worsening of all four well-being outcomes among women (Figure 2, left panel). We find that moving from no containment to average levels of containment is associated with a 13 percentage point (pp) increase in the likelihood that feelings of depression have worsened, and a 20 pp increase in the likelihood that feelings of tiredness have increased. Containment is also associated with a significant increase in depression, feeling more anxious, and feeling less safe.

Figure 2. Containment and female well-being, socioeconomic and nutritional Outcomes

Notes: (i) These figures report the coefficients of regressing female well-being outcomes (left) and socioeconomic and nutritional outcomes (right), on district-level containment. (ii) ‘Below median consumption’ refers to indicators for the share of food categories for which the respondent's intake is below the gender-specific district-level median pre-pandemic, as per the National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4, 2015-16).

The right panel in Figure 2 shows the relationship between containment, and socioeconomic and nutritional outcomes. Households in higher containment areas experienced decreased income and increased food insecurity. Moving from no containment to average levels of containment is associated with 0.6 additional household members having reduced income and an 8 pp increase in the likelihood of reduced daily meals. Comparing current consumption to pre-pandemic levels of consumption from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 4), we find that moving from no containment to average levels of containment is associated with a 13 pp increase in the share of food categories for which a woman's consumption is below her district's pre-pandemic median4.

Family structure and vulnerable women

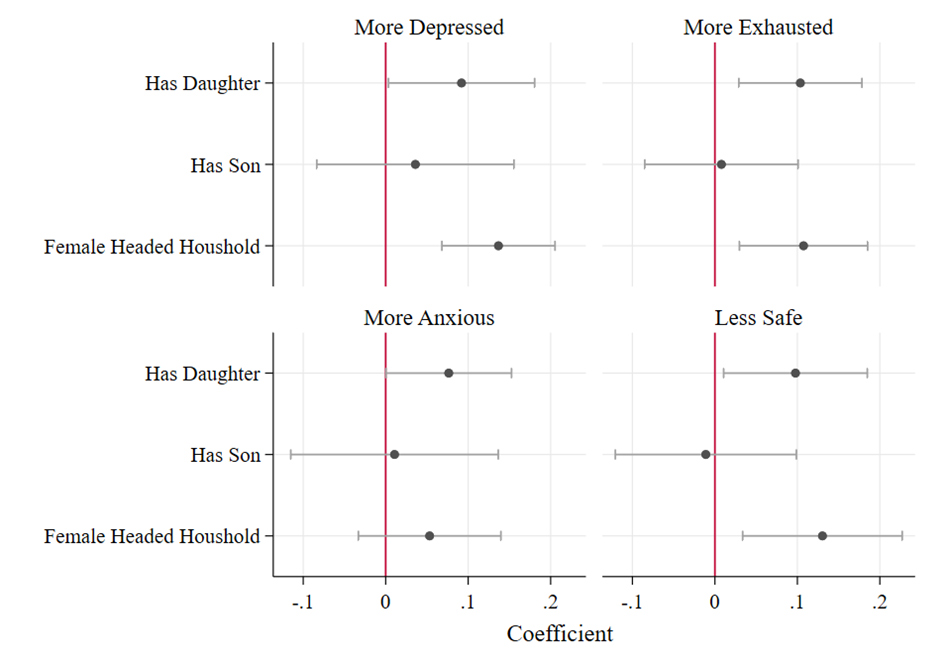

Lastly, we examine how the relationship between the Covid-19 shock and the outcomes of interest vary with the pre-existing vulnerability of women. Recent evidence from high-income settings suggests that working mothers with young children are particularly affected by lockdowns, perhaps due to the lack of adequate childcare (Zamarro and Prados 2021). While female labour force participation in India is relatively low, traditional gender norms may make women particularly vulnerable at times of socioeconomic stress. We find that the negative relationship between the pandemic and mental health is significantly exacerbated for women who have daughters. A woman is 9 pp more likely to have worsening feelings of depression and 10 pp more likely to have worsening feelings of tiredness if she has a daughter (Figure 3). Having a daughter is also associated with an increase in anxiety and reduction in feelings of safety. This is consistent with the existence of strong son preference in India, where giving birth to daughters may lower a woman's status within the household (Jayachandran 2015).

Figure 3. Household structure and female well-being

Note: These figures report the coefficients of regressing female well-being outcomes on indicators for having a daughter, having a son, and living in a female-headed household.

The adverse effects on well-being are also worsened when the head of the household is female, although we would like to note that a female-headed household's socioeconomic status could also be systematically different from male-headed households, as female heads are more likely to be widows and live in households without male earners. When the respondent lives in a female-headed household, she is more likely to have worsening feelings of depression and exhaustion, and an increased likelihood of feeling less safe.

Policy implications

While potentially crucial from the perspective of public health, containment measures in India are associated with large negative consequences for both standard socioeconomic outcomes and outcomes that are harder to observe and measure, like mental health. The effects of containment policies may be similar in other low-income contexts with limited social insurance. In such settings, more vulnerable populations, such as women, may be particularly affected by both the direct effects of the pandemic, and related policies such as containment. Our findings suggest that policymakers should target aid – particularly access to food – to vulnerable households and women.

Notes:

- Representativeness of the sample is assessed here.

- In cases where the household head was female, the female head completed both the head questionnaire and the questionnaire designed for the female respondent.

- It is difficult to assess the effects of lockdown policies by comparing two countries with different policies since countries may differ in many other ways, leading their citizens to have very different outcomes. In contrast, in India, since two districts in the same state, with similar formal institutions and similar populations, may have very different lockdown policies, we can compare outcomes across similar districts with different containment intensities.

- For men, the effect is smaller and not statistically significant.

Further Reading

- Afridi, F, A Dhillon and S Roy (2020), ‘How Has Covid-19 Crisis Affected the Urban Poor? Findings from a Phone Survey’, Ideas for India, 23 April.

- Bau, N, G Khanna, C Low, M Shah, S Sharmin and A Voena (2021), ‘Women's Well-Being During a Pandemic and its Containment’, NBER Working Paper No. 29121.

- Egger, Dennis et al. (2021), “Falling living standards during the COVID-19 crisis: Quantitative evidence from nine developing countries”, Science Advances, 7(6).

- Jayachandran, Seema, “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries”, Economics, 7(1): 63–88.

- Zamarro, Gema and María J Prados, “Gender Differences in Couples’ Division of Childcare, Work and Mental Health during COVID-19”, Review of Economics of the Household 19(1): 11-40.

20 September, 2021

20 September, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.