Despite improved connectivity, deep-rooted gender norms continue to shape access to and use of mobile technologies by women in India. This note discusses preliminary findings from a study, which suggests that the share of women who believe that supervised or unsupervised use of phones is appropriate increased significantly in the initial period after distribution of free phones under Sanchar Kranti Yojana in Chhattisgarh, indicating that access led to liberalisation of norms.

Despite expansion of mobile phone availability and network connectivity in India, deep-rooted gender norms continue to shape access to and use of mobile technologies by girls and women. In 2018, as part of an effort to address this digital divide, the state government of Chhattisgarh led an initiative to provide free smartphones to millions of women across the state under a programme called Sanchar Kranti Yojana (SKY). This presented a unique opportunity for us1 to study how norms governing phone use change when phones are provided directly to women2.

In recent research, our team surveyed 1,696 SKY-eligible3 married women – a randomly selected half just before and half just after the date of phone distribution – to get an initial glimpse of the extent to which the programme was able to shift binding gender norms. The key assumption for our analysis is that little apart from receipt of SKY phones changed over the short period of time separating the pre-distribution and post-distribution surveys4. Surveys took place between August and November 2018 – in pre-distribution villages, on average, women were surveyed 17 days prior to the first day of distribution, while in post-distribution villages, on average, women were surveyed 18 days after the first day of distribution.

Although we know it is likely that the view of our respondents’ husbands also matters for phone use (and may also have changed due to phone distribution), for this study we focus on how the women themselves have experienced the programme, as we are particularly interested in how involvement in women’s self-help groups (SHGs) shape norm shifts. We present some of our headline findings below.

Gender norms around phone use in India

Prior to initiating fieldwork, we conducted extensive primary and secondary research to help us understand the normative environment that women face in India. Our effort culminated in a 2018 report, ‘A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India’ (Barboni et al. 2018). We find that norms around phone use are closely tied to norms around marriage. For example, unmarried women are expected to stay chaste in preparation for finding a suitable husband; mobile phone use is considered a potential threat to this purity. In qualitative interviews we consistently heard that people may question what a girl was using the phone for and whether these activities were ‘proper’. For married women, the strong expectation that wives would assume sole household and childcare duties implied a general sentiment that women would have no use for a mobile phone, as they were not necessary to complete daily duties5. To capture the nuance of how people organised their thoughts around who was using the phone and for what purpose, we asked married women to report on their own beliefs about the propriety of phone use by married and unmarried women separately. We also specified if the use was supervised or unsupervised, meaning we covered four hypothetical situations in total – married women using a phone with supervision, married women using a phone without supervision, unmarried women using a phone with supervision, and unmarried women using a phone without supervision. For each of the four scenarios, a belief that it is appropriate is considered to be less conservative or constraining.

All norms relaxed – but unsupervised use remains contentious

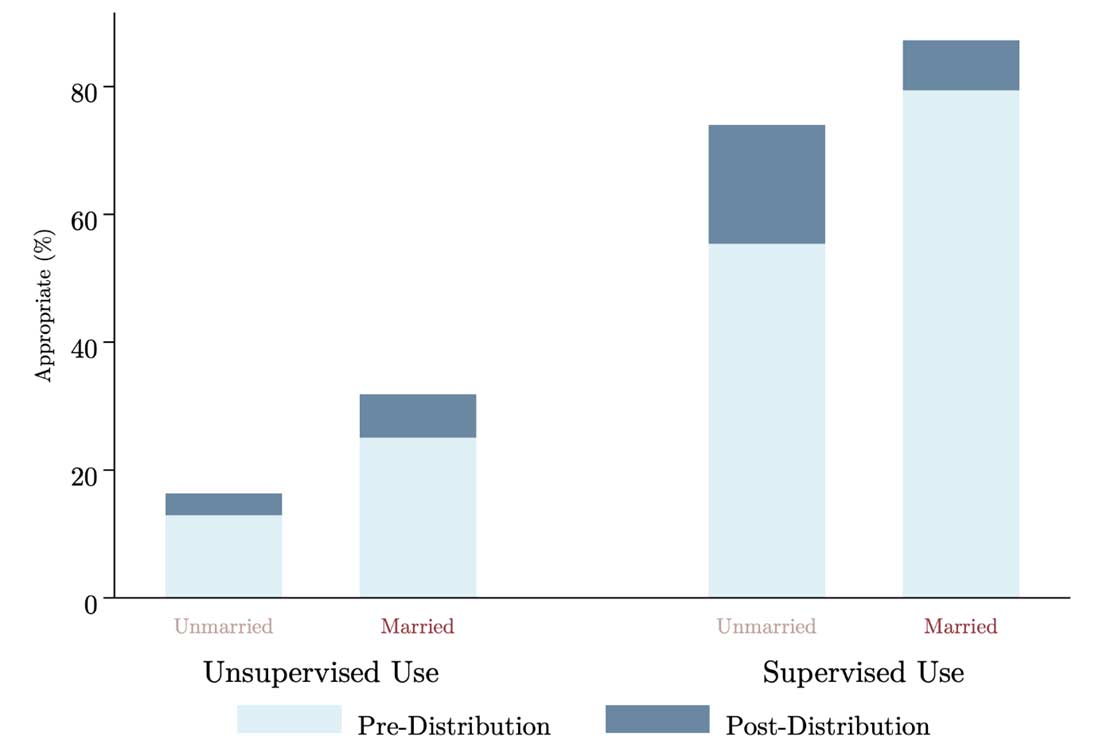

Figure 1 shows that the share of women who believe each of the four scenarios is appropriate increased significantly in the post-distribution period, indicating that phone distribution led to a liberalisation of norms. The height of the light blue bar shows the share of respondents who reported each use case was appropriate before the distribution of smartphones; the dark blue bar shows the increase in the share post distribution. Norms around supervised phone use by unmarried women loosened the most, while loosening around the other three scenarios was smaller and about equal. However, we also see supervised use continues to be thought of as more appropriate than unsupervised use, regardless of marital status. This suggests that women may continue to face resistance to using phones without restriction. Of course, these estimates only tell us about the overall change in the normative environment, and thus mask disparities in norms that poor or vulnerable women may face. Using key demographic characteristics about our respondents, we turn next to exploring heterogeneity in these changes.

Figure 1. Liberalisation of gender-based phone norms after smartphone distribution

Notes: (i) Graph is based on responses from 1,694 married women. “Don’t know” and “refuse” responses have been excluded. (ii) p-value is the probability of getting results at least as extreme as the results observed, given the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. A p-value lower than a mentioned significance level would be considered statistically significant (if p < 0.01, it is statistically significant at the 1% level). (ii) *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the p < 0.10, p < 0.05, and p < 0.01 levels, respectively. All four post-distribution increases are significant at the 0.05 level.

Norms around unsupervised use relaxed among those with fewer barriers

Another key finding from our earlier analysis was that gaps in phone use persisted across many of the standard demographics associated with higher women’s social status, including educational attainment and urbanicity. Thus, we knew it would be necessary to better understand the heterogeneous impact of the smartphone distribution across women’s characteristics. To best capture the impact on barriers that may influence our respondent women’s engagement with their smartphones, we focussed on the norms that govern married women.

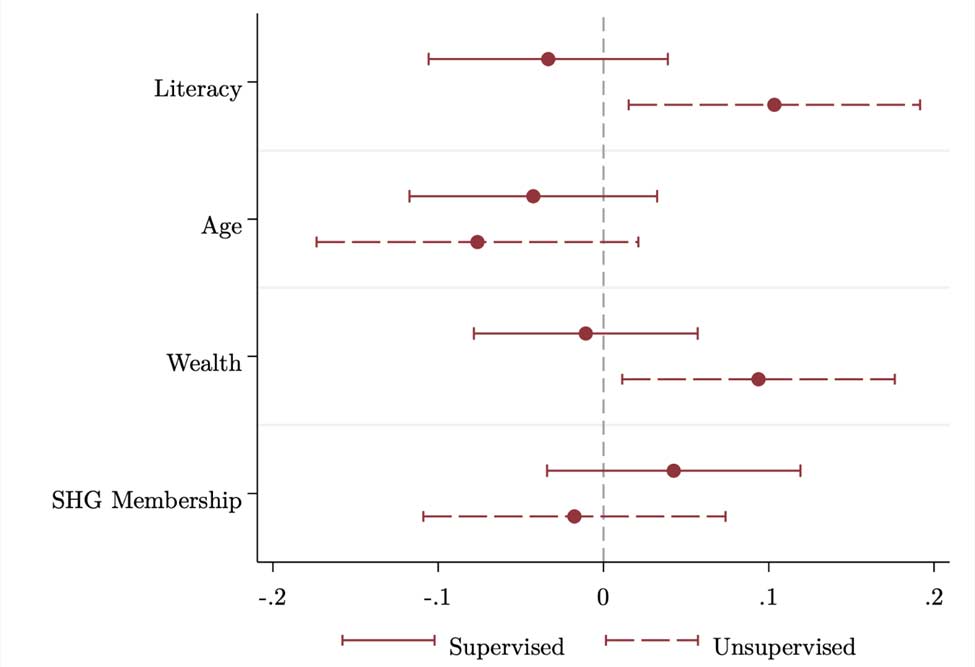

Figure 2 shows changes in norms around unsupervised use (dashed bars) and supervised use (solid bars), both by married women. This figure depicts the heterogeneous, short-term effect of the SKY programme on each norm by education (literate versus illiterate women), age (young versus old)6, income (women living in wealthier versus poorer households)7, and SHG membership (women that are members of SHGs versus those who are not). A vertical line at zero has been included to help benchmark if the effect is significant – that is, if there is a significantly different heterogeneous effect in post-distribution norms, by any of the above-mentioned characteristics.

None of these heterogeneous effects of supervised phone use by married women (solid bars) are statistically significant. However, more literate women and women from wealthier households are more likely to positively update norms around unsupervised use (dashed bars). In other words, women who face lower economic barriers (that is, are more educated and come from wealthier families) liberalised to a greater extent than their less educated, poorer counterparts.

Figure 2. Liberalisation of norms around phone use by married women, across education and wealth levels

Notes: (ii) Includes responses from 1,694 married women. “Don’t know” and “refuse” responses are excluded. (ii) A confidence interval is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects. A 95% confidence interval, means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect. (iii) Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals represent the interaction term of the demographic and the post distribution period. (iv) Robust standard errors have been clustered at the village level. (v) Wealth is measured as per capita household income in the past 30-days.

Looking ahead

It is clear from our initial exploration that overall the receipt of SKY smartphones liberalised norms among women, at least on a very short-term time horizon. As we look ahead, it will be important to track disparate norm shifts, as women who are already comparatively worse-off may face systematically more conservative gender norms. This becomes particularly true in the time of Covid-19, which may have exacerbated existing divides. We would also like to enrich these findings with a similar analysis for our respondents’ husbands, to understand the difference in their experience with the distribution. We also see initial evidence for paying careful attention to SHG membership. While our estimates were not significant, the positive correlation we see between SHG membership and increased acceptance of supervised use suggests women with SHG connections may make bigger strides in phone use over time. In addition to tracking how trends may shift for specific vulnerable groups of women, questions remain about what the medium- and long-term effects will be, and what additional support may be needed to maximise the impact of SKY phones. To answer these questions, we will utilise results from a ‘randomised controlled trial’ that has been in progress over the past three years. As part of this experiment, we provided phone training to over 10,000 women in 180 villages across Raipur district. In addition, for over two years, a subset of these women have been receiving pre-recorded messages about maternal and child health, nutrition, and government services, as well as participating in live “pull calls”, where they provide information on their wellbeing and experiences. Ultimately, this experiment will allows us to explore both the role of training in phone engagement and the role that the phone-based information service meant to create a female-focused use case for mobile phones, can play in shifting norms and uptake. As these activities draw to a close this year, we will gain deeper insight into how holistic interventions to deepen women’s engagement with mobile technology can be designed.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- The team comprised researchers from Duke University, Harvard University, University of Southern California, University of Warwick, and Yale University,

- This project is part of a larger project on self-help groups in the state of Chhattisgarh that entails a collaboration with the Chhattisgarh State Rural Livelihood Mission (CGSRLM), funded by a grant from the Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy (IWWAGE) – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University.

- The programme aimed to distribute smartphones to the female head of household (as per the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC)) in all villages with a population of 1,000 or more as per the 2011 Indian Census. Smaller villages situated in local government units (gram panchayats) with at least one qualifying village were also eligible.

- This was confirmed by checking for a balance in covariates (basic demographics), such as literacy and socioeconomic status, between the samples.

- These findings are from before the Covid-19 pandemic, which could have implications for phone and gender norms.

- We express age in terms of whether women are younger or older than age 30.

- Household income per capita was split into quintiles. A quintile measure ranks and divides the dataset into five equal parts such that, if values of consumption are listed in ascending order, the bottom quintile would refer to the bottom 20% values in terms of wealth. Wealthier households include the top three quintiles.

Further Reading

- Barboni, G, E Field, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner and CT Moore (2018), ‘A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India’, Evidence for Policy Design Report.

13 October, 2021

13 October, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.