Understanding how exit decisions of workers are affected by their ability to voice their concerns, is a central question in labour economics. Based on an experiment in 12 garment factories in Karnataka around the time of a wage hike, this article shows that providing workers a channel to express grievances – through an anonymous employee satisfaction survey – reduces quit rates, especially for those most disappointed with the wage hike.

The extent to which workers feel their voices are valued and accounted for in decision-making is an important component of their relationship with the firm. The availability of effective channels for workers to voice their concerns can play an important role in their decision to continue with or leave their current employer.

The seminal work of Hirschman (1970) proposed the idea that when consumers, workers, and citizens, face an unsatisfactory environment, they either voice their discontent to create improvement, or exit the relationship. Although multiple studies test Hirschman’s theory by estimating associations between measures of voice and firm outcomes, there is little causal evidence from real-world settings. As part of a recent study, we conducted a field experiment to test the Hirschman hypothesis, by enabling workers in Indian garment factories to have a voice through an employee satisfaction survey (Adhvaryu, Molina and Nyshadham 2019).

Background

We partnered with Shahi Exports, Private Limited (Shahi), the largest readymade garments exporter in India. At Shahi – as in the rest of the garment industry – wages for factory workers are benchmarked to the government minimum wage, which is largely determined at the state level. Every year, the state government makes adjustments to the dearness allowance component of the minimum wage, to account for inflation. Every five years, the government adjusts the ‘basic’ wage level, which typically results in much larger increases than the annual inflation adjustments. In 2016, the year we conducted this study, only the dearness allowance adjustment was made. The last ‘basic’ wage hike prior to this was in 2014.

As is the case in many manufacturing firms in low-income contexts, the turnover is high at Shahi, with annual attrition being close to 50%. Anecdotal evidence suggests that worker attrition is especially high after these annual firm-wide wage increases, a fact that may in part be explained by the potential disappointment brought about by an increase that is smaller than anticipated.

Surveying worker expectations

In May 2016, before workers were made aware of how the annual minimum wage hike would translate into an increase in their take-home pay at Shahi, we conducted a baseline survey to elicit worker expectations about the pending wage hike. We surveyed a randomly selected sample of approximately 2,000 workers from 12 factory units in Karnataka. Workers were asked how much they expected take-home wages to increase the following month. They were also asked about the wages they would potentially receive at a job they would most likely have if they did not work at Shahi.

Of the baseline sample, approximately half were randomly selected for the intervention, an anonymous employee satisfaction survey. The survey created an opportunity for respondents to express whether they agreed or disagreed with various statements about their job. For example, whether it is difficult to ask others for help, and whether supervisors encourage learning. Respondents were also asked about their general satisfaction with their job, wage, supervisor, and overall work environment. The intervention was carried out after the wage hikes were implemented at the beginning of June 2016, over a period of one month.

Impact of the intervention

Workers were on average quite disappointed by the wage hike. Responses to the baseline survey revealed that the workers’ expected wage hike was substantially higher than the actual hike. Workers expected a hike that was roughly three times the size of the realised increase, which falls in between the sizes of the most recent wage hike in 2015 and the larger wage hike in 2014. On average, workers expected to earn about US$17 (16% of total salary) more per month than their realised post-increment monthly wage.

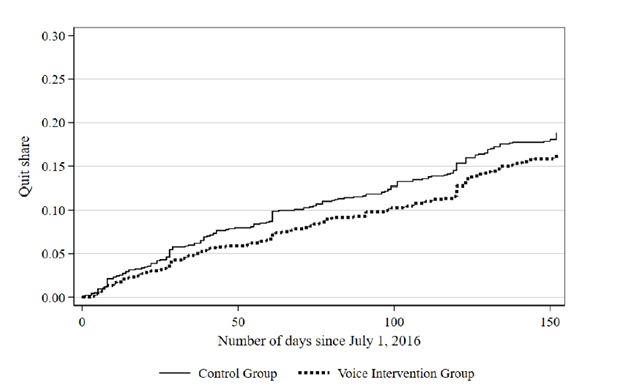

Results also show that the intervention reduced quit rates. Specifically, we found that those who were subjected to the intervention were, on average, 20% less likely to quit than the others in the period from July to November 2016. Figure 1 shows the cumulative share of the sample that left the firm, starting in July 2016 (the first month after the voice intervention) until the end of November 2016. By the end of November, quit shares were approximately 2 percentage points lower in the intervention group than in the group that did not receive the intervention.

Figure 1. Quit rates among workers that received the intervention, and those that did not (control group)

Importantly, the reduction in the quit rates was driven by the workers who were most disappointed by the wage hike. For those who were not disappointed at all, the intervention had no statistically significant effect. For those at the average level of wage disappointment (US$17), workers who received the intervention were 19% less likely to quit than other workers. These results suggest that the intervention worked primarily by mitigating disappointment.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we demonstrated that enabling workers to have a voice can reduce quit rates, especially for the most disappointed workers. Despite its importance, giving workers a voice can be challenging in low-income countries, where the rapid growth of the manufacturing sector has greatly expanded opportunities for employment but has also created situations in which large low-income workforces have few channels for expressing grievances because of established workplace practices, ineffectiveness of available channels, or fear of retaliation. The recent advent of short message service (SMS) and app-based technologies for anonymous communication with employers may make channels for grievance redressal more accessible to workers.

In ongoing research, we are testing the impact of the provision of an anonymised two-way communication tool that allows the workers to raise any workplace concern anonymously though SMS and allows the Human Resources personnel to communicate with the complainant through the same channel (trial complete and analysis in progress), as well as the impact of providing incentives to Human Resources personnel for timely resolution of grievances along with such tools (trial ongoing).

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Further Reading

- Adhvaryu, A, T Molina and A Nyshadham (2019), ‘Expectations, wage hikes, and worker voice: Evidence from a field experiment’, NBER Working Paper No. 25866.

- Hirschman, AO (1970), Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

11 January, 2021

11 January, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.