Ahead of International Women’s Day, Tanya Rana and Neeha Susan Jacob categorise and analyse scheme allocations through the Union Budget’s Gender Budget Statement (GBS), by looking at what schemes various ministries and departments prioritise under the two parts of the GBS. They discuss issues of arbitrary classification, inclusion of schemes that are not entirely women-centric, and allocations that are inadequate to meet scheme objectives. They emphasise the need for monitoring and unambiguous scheme classifications to achieve financial priorities for women's empowerment.

Follow I4I's Women's Month campaign and join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

In 2022, India ranked 135 out of 146 countries on women’s economic, social, and political empowerment (World Economic Forum, 2022). Against this backdrop, how can the state play a role in addressing women’s comprehensive empowerment? One way is through allocating monies for women and girls through the Gender Budget Statement (GBS)1. Also known as the Gender Responsive Budget (GRB), the GBS is not a separate budget for women and girls but a statement of financial prioritisation through existing schemes (Government of India, 2023).

In FY2023-24, the GBS constituted only 5% of the Government of India’s overall expenditure budget, a 0.2% decrease from previous year allocations (as per the Revised Estimates). Further, over the years, out of total allocations in the GBS, Part B has had a greater proportional allocation than Part A (Kasliwal 2023). In FY2020-21, over 85% of actual expenditure was under Part B. While this was reduced to 54% in FY2021-22, allocations (as per the Budget Estimates (BE)) rose to 61% in FY2023-24. This suggests a dilution in financial prioritisation of women and girls through schemes in the GBS. It therefore also begets important questions: what sectors does the government prioritise spending on for women and girls? Correspondingly, what are the gaps in the GBS?

We attempt to analyse the trends in allocations for different women-specific priorities. We analytically categorise2 the government’s large social sector schemes in the GBS and analyse its implications for women’s needs. This allows us to understand the government's prioritisation for bridging gender gaps. We simultaneously discuss the challenges in the presentation of the GBS.

What does the gender budget prioritise?

The GBS assigns either 100% (Part A) or at least 30% (Part B) of scheme allocations for gender3 priorities. Part A includes ‘women-specific’ schemes, with 100% allocations for women and girls. Part B, on the other hand, encompasses ‘pro-women’ schemes, with at least 30% of overall scheme allocations for women and girls.

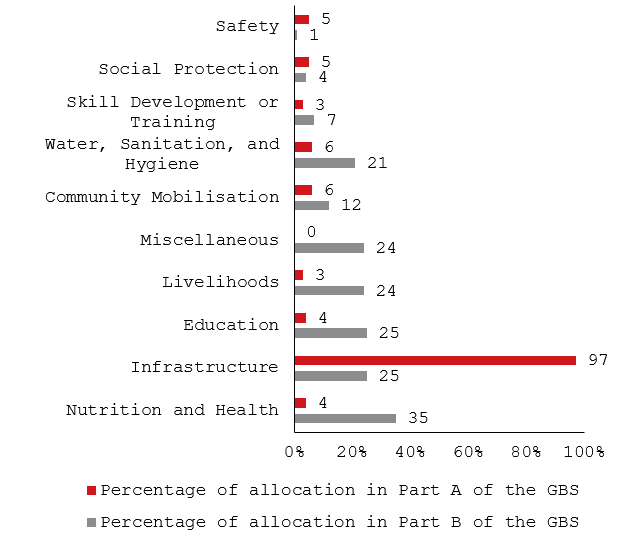

Figure 1 depicts category-wise prioritisation for women and girls in Part A and Part B of the GBS. Infrastructure overwhelmingly constitutes the highest share (97%) of overall Part A allocations in FY2023-24. This ranges from promising the construction of houses in rural4 and urban areas to be owned by women to the provision of ‘surveillance’ through CCTV cameras (Government of India, 2018a). Leaving out other important aspects such as skill development and livelihoods, education, nutrition and health, and safety, which contribute towards holistic gender empowerment, suggests little to no scope for bridging gender gaps.

Looking at allocations in Part B, 35% of overall allocations were for nutrition and health, followed by infrastructure, education, and livelihoods. Several schemes also do not present a clear scope for targeting women and girls through the GBS.

Figure 1. Allocations for various women-specific priorities, as a proportion of total Part A and Part B allocations in the GBS

A deep-dive into how different ministries and departments have tried to balance gender priorities in the Union Budget 2023-24 shows that several of them either misclassify or inadequately prioritise existing schemes. We discuss some examples below.

Women and Child Development

All the key schemes of the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) feature in the GBS. In Part A, the listed schemes focus on infrastructure, nutrition and health, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and community mobilisation. Importantly, Mission Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, which focusses on improving nutritional outcomes among women, adolescent girls and children, has been assigned only 4% of overall scheme allocations, despite being the ministry’s largest scheme, and in Part A of the GBS. In fact, its placement in Part A can also be contested, as the scheme covers boys and includes other activities, like Jan Andolans for mobilising the village around collective issues of nutrition and health.

A similar misclassification can be seen for Mission Shakti’s Samarthya sub-scheme for the economic empowerment of women, which is in Part A of the GBS. While the scheme constitutes 97% of overall allocation in Part A, it constitutes far less than 30% of the required allocation (only 3%) in Part B. There is also double counting, as Samarthya is presented in both Part A and Part B.

Rural Development

The Department of Rural Development’s schemes in Part A constitute 100% of its overall scheme allocation in the GBS. These schemes, however, focus only on infrastructure and social protection for women. Even then, classifying Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Gramin (PMAY-G) as an entirely women-centric scheme is dubious. While the scheme encourages assignment of houses in the name of women, as of 1 January, 2023, only 26% of constructed houses were solely owned by women (Jacob et al. 2023).

Materially poor women are at the forefront of the ministry’s National Livelihood Mission - Aajeevika. Similarly, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) intends to provide one-third of overall jobs created to women. While the allocations also reflect this intention, constituting more than 30% of overall scheme allocations for women, it is important to map this against the entitlements provided. With little or no monitoring of allocations in the GBS, it is difficult to justify why even though 42% of MGNREGS allocations are for women, they constituted only 25% of skilled and semi-skilled MGNREGS workers as on 28 February, 2023.

Social Justice and Empowerment

Under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE), only the Post Matric Scholarship for Schedules Castes features under Part B. If the objective of the ministry is to reserve a certain proportion of the scholarship amount for girls, it does not explain why several other scholarship schemes of the ministry do not assign any allocation in the GBS. For example, the Pradhan Mantri Young Achievers Scholarship Award Scheme for Vibrant India (PM-YASASVI) is not featured in the GBS at all. This assignment of the scheme for reducing gender disparities in education, therefore, seems to be an afterthought.

Drinking Water and Sanitation

Like the MoSJE, the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation presents only one flagship scheme – the Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin (SBM-G) – in Part B of the GBS. As a percentage of overall scheme allocations, allocations for SBM-G increased by 3%, to 32% in FY2023-24. Allocations identify the iniquitous burden of poor sanitation and hygiene on women and children (Government of India, 2017).

However, flagship schemes, like the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), find no mention, despite acknowledging rural women’s empowerment as one of its objectives (Government of India, 2019). Benefits of tap water connections can be directly attributed to reducing gender disparities, as women and girls tend to be primarily responsible for fetching water for the entire household (Mathur 2022), also recognised by the scheme’s operational guidelines. Therefore, the scheme should have been appropriately accommodated in the GBS too.

Health and Family Welfare

The Department of Health and Family Welfare presents several schemes for women under Part B of the GBS. Looking at schemes with high allocations in FY2023-24, a category-wise prioritisation that is specific to women and girls is unclear. This is a major limitation in the GBS exercise, which does not require departments to provide a basis for including a scheme.

For example, infrastructure maintenance, a sub-component under the flagship scheme of National Health Mission (NHM), has been allocated Rs. 64.72 billion. Presented in Part B, it constitutes a whopping 95% of overall scheme allocations. According to guidelines, infrastructure maintenance aims to provide salary support to various health functionaries, including auxiliary & nursing midwife and lady health visitors training schools, among many others (Kapur et al. 2023). Similarly, for example, the intention of allocating 50% of overall scheme allocations for women under the head of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi is unclear. Despite being high, these allocations contribute to the ambiguity in including certain schemes under the GBS.

Education

Schemes of the Department of School Education and Literacy (DSEL) and Department of Higher Education (DHE) majorly fall under Part B of the GBS, comprising 10% and 7% of the GBS, respectively. Under DSEL, PM Poshan Shakti Nirman (PM-POSHAN; the erstwhile Mid-Day Meal Scheme) allocates 50% of its total budget for pro-women schemes (that is, in Part B). Other DSEL schemes include Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan, Navodaya Vidyalaya Samiti, and Samagra Shiksha, where 30% of total scheme allocations are included in the GBS. Moreover, there have not been any changes in proportional allocations for other schemes of these departments since FY2021-22.

All schemes under DSEL fall under the category of education. PM-POSHAN also has a nutrition component since the scheme aims to improve nutritional status of children in grades 1 to 8. Besides education, the flagship scheme of Samagra Shiksha also falls under the categories of infrastructure and WASH (for example, the construction of separate toilets for girls). As reducing social disparities is one of the major objectives of the programme, even the allocation target of 30% of the total expenditure budget for this scheme under Part B of the GBS seems minimal. In fact, only 8% of Samagra Siksha’s approved budgets in FY2022-23 were assigned for the component ‘Gender and Equity’ (Bordoloi et al. 2023).

Law enforcement

Infrastructure and safety are also the two major categories of schemes of the Department of Police (under the Ministry of Home Affairs). Two of the department’s schemes, namely the Safe City projects and Emergency Response Support System (ERSS), fall in Part A. But since the GBS is not a separate budget document, presenting higher-than-original scheme allocations in the GBS cannot be validated5. At the same time, ERSS is not exclusively a women-specific program. It covers all citizens in need of emergency assistance.

Petroleum and Natural Gas

Encouraging cleaner and safer fuel for every household, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas aims to provide subsidised Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) connections to poor households. Women spend a disproportionate amount of time on unpaid domestic work and caregiving activities, compared to men in both rural and urban areas (Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, 2020). Correspondingly, building on the patriarchal assumption of housework as women’s work, this scheme is included in Part A. As a subsidy, this is also a social protection measure. Its intent, however, is challenged by the rise in LPG prices, which has forced women to return to using traditional cookstoves, thereby reducing their dependence on this subsidy amount (K, Vandana 2023).

Skill Development

The Skill India programme under the Ministry of Skill Development is a new addition to Part B. A composite of three sub-schemes – Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana 4.0, Pradhan Mantri-National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme, and Jan Shikshan Sansthan – this programme promotes women’s skill development and training. While the scheme coverage goes beyond women (and despite being in Part B) 100% of the overall scheme allocations have been assigned to them. Yet again, this is contradictory to not only scheme objectives, but also to the design of the GBS.

Housing and Urban Affairs

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has two schemes in the GBS. Categorised under infrastructure, the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana-Urban (PMAY-U) ensures pucca (or permanent) houses to every urban household in India. Like PMAY-G, PMAY-U encourages the ownership of houses in the name of women or jointly with men. PMAY-U falls in Part A, contributing to a significant proportion (29%) of Part A and 11% of overall GBS in FY2023-24.

Until FY2022-23, 50% of overall allocations for Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana - National Urban Livelihood Mission were assigned to Part B. The scheme is meant to mobilise urban poor women for livelihood enhancement (Government of India, 2018b). In FY2023-24, however, no allocations were assigned. These ad-hoc assignments from year-to-year indicate a weak commitment to the GRB exercise.

Conclusion

The road to truly equitable gender relations seem unrealised in the Union Budget 2023-24. The social sector ministries and departments discussed in this article face the persisting challenges of classification and inadequate allocations in the GBS. Even though a higher proportion of the GBS is for Part B schemes, the intention behind scheme weightage based on gender remains ambiguous. This reduces the GBS’s ability to act as a mechanism for bridging gaps through specific financial prioritisation for women and girls, amidst competing needs across categories and scopes of ministries and departments. For instance, if the state aims to focus on infrastructure, the goalposts must align with the contextual factors that make these facilities amenable to their empowerment in both private and public spheres (OECD, 2021). In fact, the recently released guidelines for MWCD’s schemes focus on convergence with other ministries. With overall inadequate allocations in the GBS, and lack of clarity on its gendered impact, this intent might also remain unrealised.

Lastly, the lack of monitoring and disaggregated women- and girls-specific objectives in scheme guidelines contribute to the ambiguity of assigning schemes to the GBS altogether (Raman 2021). Financial prioritisation for women’s economic, social, and political empowerment through the GBS will, therefore, remain a pipedream unless these disparities are resolved.

Notes:

- GBS is a ‘reporting mechanism’ for ministries and departments to review their schemes through a gender lens and, correspondingly, assign (or allocate) finances for women and girls.

- We select social sector ministries and departments, and analytically categorise schemes within these ministries and departments based on broad women-specific categories (or goals). A scheme can fit more than one category: for example, Safe City projects encompasses components of infrastructure, safety, community mobilisation, and WASH, based on stated scheme objectives. Therefore, we don’t undertake a normative assignment of schemes across these categories. Once categorised, we calculate the percentage composition across these categories, under Part A and Part B of the GBS. This forms the basis of assessing women-specific schemes across different categories and social sector ministries and departments.

- In the policy landscape, ‘gender’ is still understood in binaries of women or men, and girls or boys.

- (PMAY-G) constitutes a whopping 62% of Part A allocations in the GBS.

- In this case, Rs. 3.21 billion was allocated to Schemes for the Safety of Women, which includes ERSS; however, the GBS assigns a value of Rs. 13 billion and Rs. 2.21 billion to the Safe City Project and ERSS, respectively.

Further Reading

- Bhasker, S (2022), ‘Break The Gender Bias: Indian Women Spend 15 Crore Workdays A Year Fetching Water, An Economic Loss Of Rs.100 Crore’, NDTV, 22 March.

- Bordoloi, M, A Kapur and S Santhosh (2023), ‘Budget Briefs: Samagra Shiksha 2023-24’, 15(5), Accountability Initiative.

- Government of India (2017), ‘Guidelines for Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin)’, Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India.

- Government of India (2018a), ‘Safe City – Framework & Guidelines’, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

- Government of India (2018b), ‘Social Mobilisation and Institution Development’, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India.

- Government of India (2019), ‘Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of Jal Jeevan Mission’, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Government of India.

- Government of India (2023), ‘Expenditure Profile 2023-2024’, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, Gender Budget (Statement 13): 166-176.

- Jacob, NS, A Mallick and A Kapur (2023), ‘Budget Briefs: Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana (Gramin)’, 15(1), Accountability Initiative.

- Kapur, A, R Shukla and S Pandey (2023), ‘Budget Briefs: National Health Mission 2023-24’, 15(8), Accountability Initiative.

- Kasliwal, R (2023), ‘The Status of Gender Budgeting in India’, Accountability Initiative, 10 February.

- Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation (2020), ‘NSS Report: Time Use in India – 2019 (January – December 2019)’, MoSPI, Government of India.

- K, Vandana (2023), ‘As LPG Prices Soar, Women Return To Toxic Traditional Stoves’, BehanBox, 7 February.

- OECD (2021), ‘Selected stocktaking of good practices for inclusion of women in infrastructure’, OECD

- Raman, S (2021), ‘What India's Gender Budgets Have Achieved’, Indiaspend, 25 January.

- World Economic Forum (2022), ‘Global Gender Gap Report 2022’, World Economic Forum Insight Report.

06 March, 2023

06 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.