In the previous part of this series, Ashok Kotwal and Pronab Sen presented an export-led development strategy employed by successful Asian countries and why India failed on this front. In this part, they trace the genesis of the present economic slowdown.

This piece was written for The India Forum by I4I Editors Ashok Kotwal and Pronab Sen: https://www.

Investment slowdown

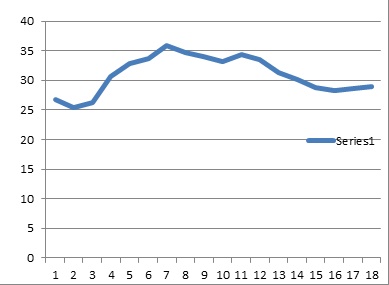

To understand the present slowdown it is useful to examine the ups and downs in the rate of domestic investment or gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) as a percentage of GDP between 2001 and 2018 as in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1. Gross capital formation as a percent of GDP

It is easy to see that GDCF as a percentage of GDP grew impressively from 25.3% in 2002 to 30.7% in 2004, and then kept growing to 35.8% in 2007 (the highest rate of investment reached so far). This was a high growth period for the Indian economy. However, it was also a period of high credit growth. The investment spree was financed by heavy borrowing by the corporate sector. Corporate exuberance during the boom period of 2002-07 partly explains the present state of indebtedness of the corporate sector, but it is a necessary corollary to a high investment/high growth development process.

In the aftermath of GFC, 2007-08, corporate investment fell. The post-2011 period is a period of decline in investment as massive corruption scandals rocked the Indian economy, and the corporate sector faced a backlash from watchdogs like the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, and from investigation agencies like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) etc. There is some recovery after 2014 but that was torpedoed by demonetisation at the end of 2016. Initial exuberance during the high growth period of 2002-08 and then the shock of GFC of 2008 are the root causes of corporate indebtedness of today.

There was a major slump in international demand after the GFC, and inevitably Indian exports slumped. There is no doubt that the slowdown in the Indian growth rate as well as in domestic investment should be attributed to this world-wide phenomenon.

What is surprising is the fact that the GDCF rate does not decline that much and in fact recovers to 34.3% in 2011. A plausible explanation for this is that in 2008, international food prices rose due to many extraneous reasons, including because following high oil prices, large food producers in North and South America shifted their land to cultivation of crops to produce crops for gasohol. This rise in world prices pulled up domestic agricultural prices in India. (Minimum support prices (MSPs) were repeatedly raised during this period.) As a result, the terms of trade shifted in favour of agriculture. This most likely brought about a significant redistribution of income in favour of the rural sector, which, in turn, gave a boost to the investment in the informal sector. This compensated to some extent a fall in corporate investment.

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that this was also a period of rising rural wages and declining poverty numbers. Perhaps the introduction of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS) helped to some extent. But the scheme took several years to get going in many parts of the country. We believe that a change in the terms of trade probably played a significant role in maintaining a high rate of investment during those years.

This episode does offer a clue as to how a transfer from the urban to rural sector suggests itself as an antidote to the present slump in aggregate demand. This is an issue that we will explore toward the end of this series.

GDCF declined steadily from 34.31% to 28.73% in 2015, and has stayed stagnant thereafter. There are two big reasons for this. First, by 2015, it had started to become clear that the Indian corporate sector was heavily indebted. As debt soared, investment growth declined. Also, at the end of 2016, the Indian economy had to suffer the enormous shock of demonetisation that hit the informal sector especially hard. A decline in the demand from the informal sector also resulted in unsold inventories of the corporate sector. In a 2017 report, Credit Suisse pointed out that 40% of corporate debt was held by firms that could not hope to earn enough to even cover their interest costs.There was an alarming growth in the corporate debt. It grew from 34.2% of GDP in 2002 to 56.8% of GDP in 2018. (Original Source: Bank of International Settlements.)

Why did corporates over-borrow? Was it just irrational exuberance? Or was it the result of the weakness of the Indian banking system? Unfortunately, it was both. After the heady days of fast growth from 2002 onwards, faster growth was anticipated despite the fact that world demand had slackened. Corporates invested heavily on the back of bank credit. Infrastructural investments – clearly essential for long-term development – also reached a peak around 2012.

Much more importantly, there is systemic moral hazard built into the Indian banking sector. Public sector banks can always rely on public revenues to bail them out. As a consequence, they have never bothered to develop a decent risk assessment system. Moreover, politicians have often directed them to loan money to their pet projects. For example, there is the present government’s MUDRA (Micro Units Development & Refinance Agency) programme that obliges banks to give small loans to informal sector businesses without collateral. Or, periodic loan waivers to farmers. All this has made the Indian banking sector prone to moral hazard.

Financing infrastructure

Infrastructural projects are typically long gestation projects. They take a long time to complete and a long time to start yielding financial returns. To preclude the strain on public revenues, the government resorted to public private partnerships (PPPs). It was both, the public sector banks as well as private banks that provided funding for these projects. Both types of lenders exhibited poor risk assessment. Non-bank financial corporations (NBFCs) also joined in the lending spree, and faced even fewer obstacles in doing so as they were not constrained by even the kind of regulation that commercial banks have to observe.

There was a great deal of infrastructural building during the years 2006 to 2012. Infrastructural investment went from 4.7% of GDP in 2006 to 8.4% of GDP in 2012, and then declined to 5.1% in 2013. It gradually rose very slightly to 5.6% of GDP by 2017 (Nikore 2019).

Large-scale projects have to face many hurdles – acquiring land and then getting environmental clearances being two of the most difficult ones. Even the most recent land acquisition legislation (2013) makes acquiring land for industrial production a complex and time-consuming process. You can now understand why private investors, especially those who had borrowed for infrastructural projects, ended up defaulting on their loans. If the project gets stuck in legal wrangles for a few years, the horizon for getting returns from the project moves away, while they are obliged to pay interest on their loans over a longer period. At some point, the project becomes worthless and investors walk away or default.

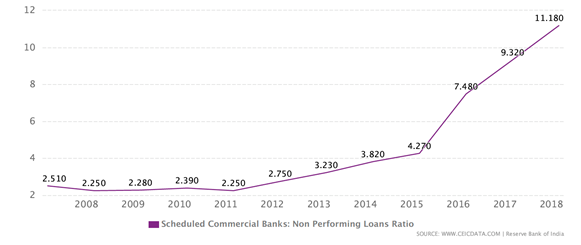

Roads and power stations can remain half-built and end up as non-performing assets on the balance sheet of the lending agency. See Figure 2 to appreciate the rise in non-performing loans ratio (defined as the ratio of ‘loans overdue by more than 90 days (defined as NPA) to the total loans’) over the last decade. Notice how steeply it goes up after 2015.

Figure 2. India’s non-performing loans ratio: 2007-2018

What happened in 2015? That was the year when RBI Governor RaghuramRajan asked the banks to clean up their bad balance sheets, and applied much greater scrutiny of their affairs. It would, therefore, be misleading to interpret this sharp rise in NPAs purely to imprudent lending in the recent past, as some of the current narratives would have us believe. It should be noted that even in developed countries, gross NPAs are around 4%. There is no reason to believe that India was consistently superior on this count; indeed to the contrary.

Thus, there was a 10-year period from 2004 to 2014, when NPAs in India were lower than the global norm. Not because of superior banking skills, but because of pervasive ‘evergreening’ of bad loans. These chickens finally came home to roost in 2015. What is happening today is a stock effect that should gradually correct itself through a combination of write-offs and much lower levels of new NPAs.

But there are new problems looming before the banking sector – a potential melt-down in the NBFCs triggered by the IL&FS crisis, and growing defaults in MUDRA loans.

When large NBFCs like IL&FS default, it also creates NPAs on the balance sheets of the banks they borrow from. When corporates cannot complete their projects, their own balance sheets as well as those of banks and NBFCs develop a large set of NPAs. This is the ‘twin balance sheet’ problem that the Indian economy is plagued with today. This is a serious problem for the economy as it results in corporates curtailing their investment and banks curtailing their lending. As of January 2019, the gross NPAs to total outstanding loans ratio stood at over 10%, and it is disproportionately borne by public sector banks.

The MUDRA loans are a different story altogether. In the aftermath of demonetisation, when the informal sector was faced with a serious liquidity crunch, MUDRA loans enabled a number of these firms to stay afloat by repaying the outstanding bank/NBFC loans. Unfortunately, things have not improved sufficiently since then for the informal sector and now they face the prospect of defaulting on their MUDRA loans.

One thing that is clear from the above account of how we got here is that this sort of problem will keep recurring until there are structural reforms in land acquisition, banking regulation, labour etc. One step was taken with the passage of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016. It allowed lenders to put a closure on bad loans that were never going to be paid back. They could write off the bad loans but could get quick access to the borrowers’ collateral that they could then liquidate. This will help in relieving the gridlock in the financial system, but not entirely. In the first place, NBFCs have very few assets other than their loan portfolios, which may not be easy to unwind. Second, MUDRA loans are non-collaterised, so there is nothing to liquidate.

There are also a number of systemic problems with India’s banking system that cannot be easily solved. First, public sector banks that hold three-fourths of the total deposits have been unabashedly used by politicians and their management is very much subject to a serious moral hazard. Second, commercial banks in India are ill-equipped to be effective lenders for long-term projects on the basis of short-term deposits. Long-term bond markets are not yet well developed in India. Third, financial institutions in India are poorly regulated.

The problems in the financial sector have now affected overall demand in the economy. Aggregate demand consists of private investment by domestic producers (rural and urban), public investment, export demand, and consumption. Demonetisation in 2016 was a serious negative shock to the rural economy that had already been reeling under successive drought years since 2014. Rural investment as well as consumption declined after demonetisation.Export demand was already declining due to slow growth in developed countries. The indebtedness of corporations dampened corporate investment. As inventories started piling up, the corporates started laying people off. Firms invest when they see signs of rising demand for their products. Presently, they see none. This in turn resulted in the slowdown of consumption growth. This is why we are witnessing signs of the onset of a more serious slowdown today.

Will the new bold initiative of corporate tax cuts help arrest the slowdown? The main idea behind the tax cut is to remove the disincentives for corporate firms to produce in India by bringing down the corporate tax rates to those prevailing in competing nations like Vietnam. But is there any reason for us to believe that this would stimulate demand by inducing corporates to increase investment? For it to work as a demand stimulant, the logic would have to be as follows: tax incentives would encourage firms to cut prices that would tempt reluctant consumers to the market and spend. But there are better ways to bring prices down – for example, a cut in the Goods and Services Tax (GST). We do not think the recently announced cut in corporate tax is an effective way to stimulate demand.

As mentioned before, corporate investment is being withheld because they do not expect any increase in consumption demand. If nobody is going to buy, why produce? We called it a bold move because at least over the short run, the proposed tax rate would also cause a substantial revenue loss to the government hurting for revenues. If the aggregate demand does not budge, the revenue loss is estimated to be very substantial – Rs. 1.45 trillion. It is worth asking if it might not have been more effective to use this huge sum to stimulate demand in a more direct fashion.

However, in the long-run perspective the move makes good sense. Nations do compete with each other to attract foreign investment and the corporate tax rate is certainly one aspect of this competition. However, it is not the only one. The ease of doing business, the integrity of the legal system to enforce contracts, the state of the infrastructure, and the quality of the labour force are equally important. In the absence of structural reforms, it seems unlikely that even in the long run the new initiative of corporate tax cut alone will make a substantial difference to India’s fortunes in attracting multinational investment.

In our story, the demand slowdown today is not just a cyclical slowdown that can be cured by a monetary measure like lowering interest rates or a fiscal measure like a tax cut. Instead, it is a combination of having missed the express bus of export-led growth with manufactures through our tardiness in carrying out structural reforms, and then the shocks of demonetisation and messy implementation of the GST that flattened the informal sector of the economy. The challenge of structural reforms is a long-standing one. The rest of the factors are of a more recent vintage.

In addition to the above factors, there is growing unease among the corporate executives about harassment by tax authorities. This stems from a peculiar worldview held by the top level of the government that all bad economic outcomes have at their source bad or corrupt people. “If we use the disciplinary organs of the state to go after everyone who could be potentially corrupt, the system will be cleansed and the economy will start humming again.” This kind of thinking may win elections but does little to perk up the economy. Demonetisation and tax raids are a testament to this. But draconian and extra-judiciary measures ensnare the innocent as well as the guilty, and make the country inhospitable for business. This is an additional reason for a slowdown of business investment over the last few years.

The analysis and arguments in this series have benefited from discussions in recent times that both authors have had with a large number of individuals, far more than can be named here. Our thanks to all of them.

Ashok Kotwal would like to thank Parikshit Ghosh, Ashwini Kulkarni, Milind Murugkar, and Bharat Ramaswami for many useful conversations.

The last part of the series is also being posted today.

Further Reading

- Nikore, M (2019), ‘Infrastructure Financing Gaps in India: Need for Focused Resource Mobilization’, Times of India Blog, 27 March 2019.

29 September, 2019

29 September, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.