While the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the pace at which technology is becoming commonplace in our lives, it has also exposed a stark digital divide, leaving a large proportion of India’s population out of this paradigm shift. Using 2017-18 National Sample Survey data, Mumtaz and Mothkoor highlight variations in digital literacy across states and union territories of the country, and discuss government efforts in this context.

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the pace at which technology is becoming commonplace in our lives. Workplaces rapidly shifting to digitally enabled business solutions, education and medical consultations going online, and contactless digital transactions being preferred and promoted are just a few examples of how technology is quickly establishing a ubiquitous presence. However, the pandemic has also exposed a stark digital divide, leaving a large proportion of India’s population out of this paradigm shift. As per the Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators for July-September 2020, on 30 September 2020, the total number of internet subscribers per 100 people in India stands at 57.29, with this number being around 3 times higher for urban India (101.74)1 compared to rural India (33.99). As per the report of the 75th round (2017-2018) of the National Sample Survey (NSS), household-level statistics reveal that only 4.4% of rural households own a computer as compared to 23.4% for urban households. In terms of access to the internet, 42% of urban households have access to the internet while the corresponding figure for rural households is only 14.9%.

While availability of digital infrastructure will play a crucial role in bridging the existing gaps, it is equally important to build digital skills among the Indian population to be able to take advantage of this infrastructure. We use household data from the 75th Round of the NSS to understand digital literacy in India, and make recommendations for a way forward in the context of several initiatives taken by the government.

Digital literacy levels in India

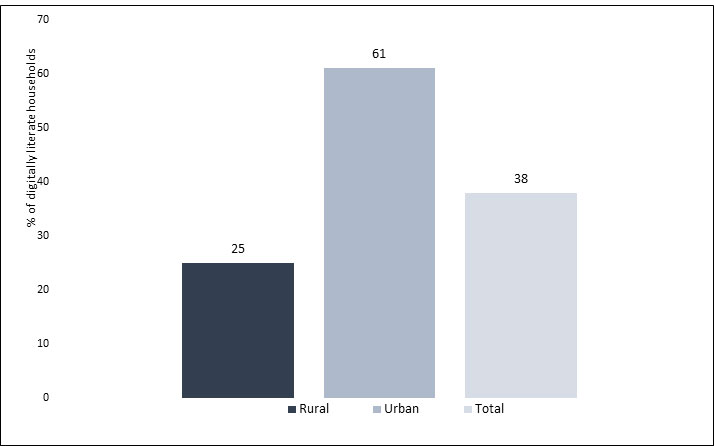

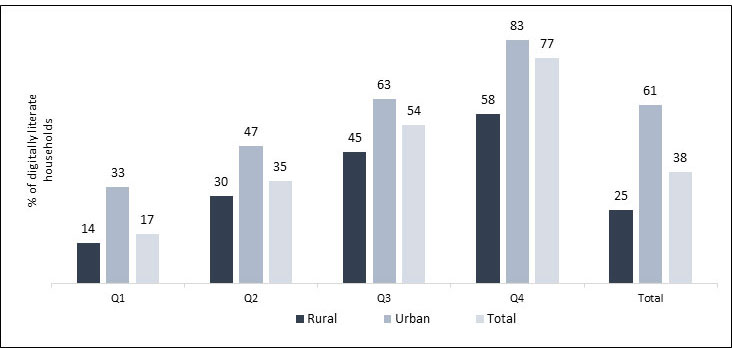

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology defines digital literacy as “the ability of individuals and communities to understand and use digital technologies for meaningful actions within life situations. Any individual who can operate computer/laptop/tablet/smartphone and use other IT related tools is being considered as digitally literate.” Based on this definition, we define households as being digitally literate if at least one person in the household has the ability to operate a computer and use the internet (among individuals who are 5 years of age and older). Based on the above definition, we find that only 38% of households in India are digitally literate. In urban areas, digital literacy is relatively higher at 61% relative to just 25% in rural areas.

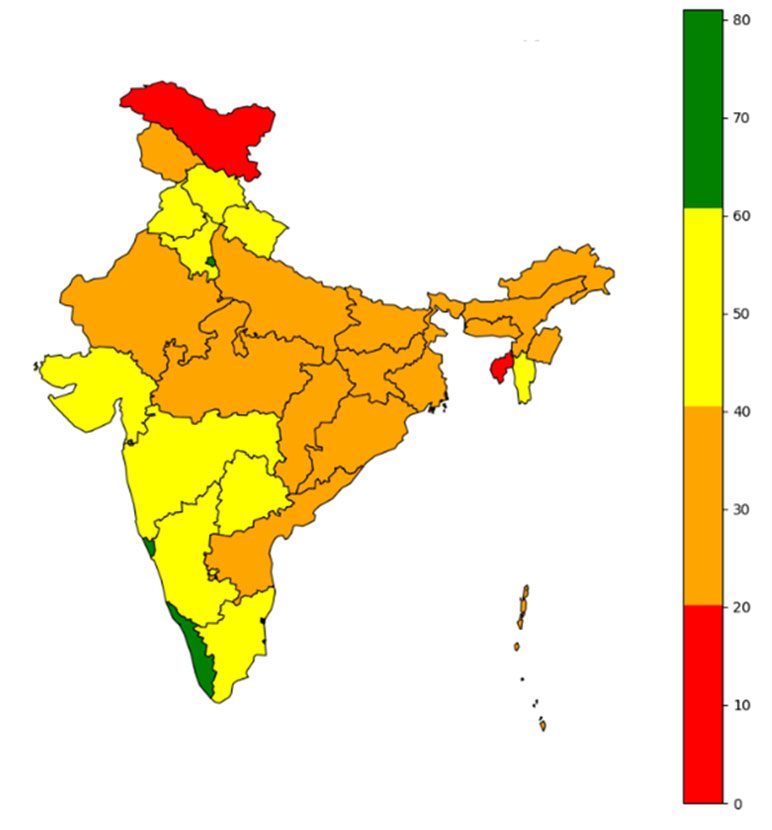

Figure 1. Digital literacy in India at the household level

Analysing digital literacy by consumption quartiles reveals that the bottom quartile2 has the lowest percentage of digitally literate households, at 17% as compared to 77% in the top quartile. Urban areas have a greater percentage of digitally literate households across quartiles, vis-à-vis rural households, by almost 17-25%. Comparing digital literacy levels across consumption quartiles within rural areas, it can be seen that the bottom quartile lags behind the top quartile by a considerable difference of 44%.

Figure 2. Digital literacy levels in India, by consumption quartiles

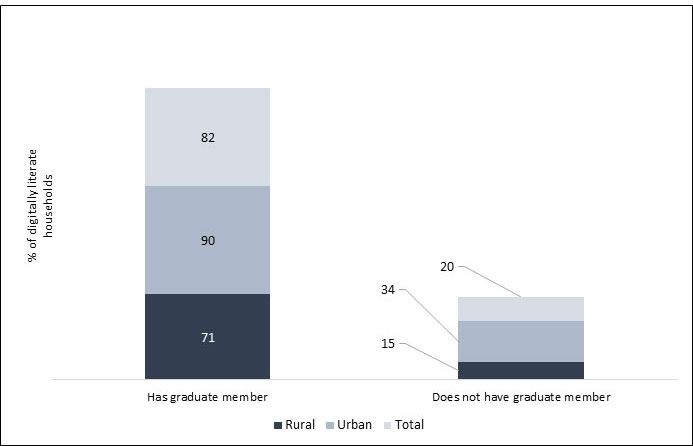

In terms of education, if a member of the household is a graduate there is a 71% chance that the household is digitally literate in rural areas, and 90% in urban areas.

Figure 3. Digital literacy levels in India, by graduation status

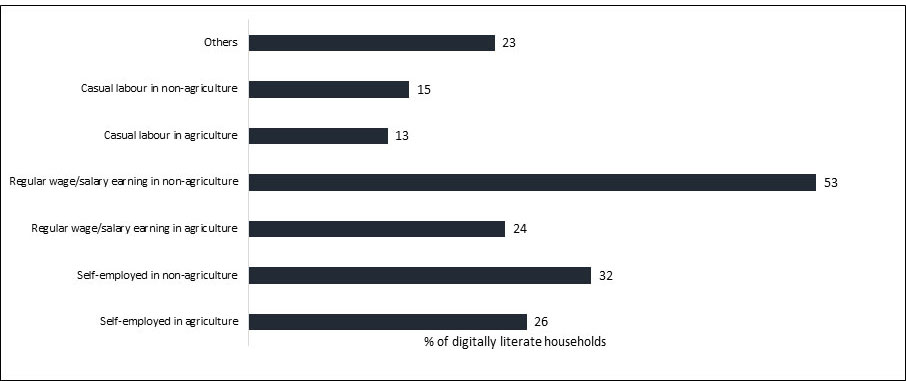

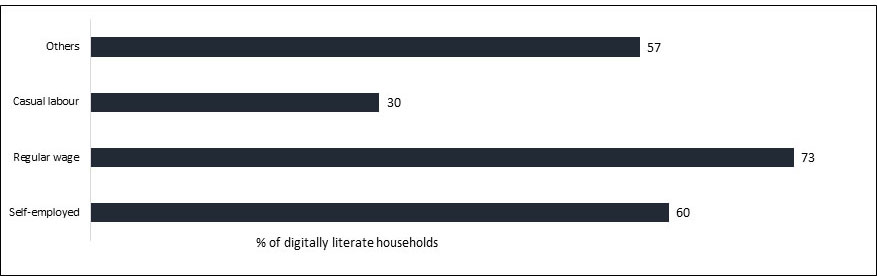

By occupation profile in rural India, households that reported to have received regular wages/salaries from non-agricultural occupations have the highest percentage of digitally literate households at around 53%. In contrast, casual workers in the agriculture sector have the lowest level of digital literacy at 13%. In urban India, digital literacy is highest among regular wage/salaried workers at 73% and lowest among casual workers at 30%.

Figure 4a. Digital literacy levels in rural India, by occupation

Figure 4b. Digital literacy levels in urban India, by occupation

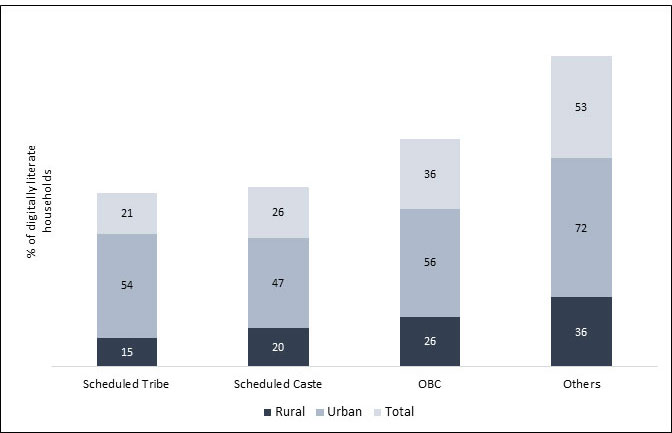

When we look at social groups, Scheduled Tribes have the lowest overall digital literacy at the household level at 21%. The rural-urban divide is evident across social groups in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Digital literacy levels in India, by social group

Digital literacy across Indian states/UTs

Lakshadweep, Chandigarh, and Goa are among the top 10% of digitally literate states and union territories in India. The rural-urban gap in Lakshadweep is remarkably low at 1%, while Chandigarh has a high rural-urban gap of 27%.

Figure 6a. Digital literacy across states and UTs, rural and urban areas combined (%)

Source: NSS data; authors’ calculations.

Note: Percentage here indicates percentage of digitally literate households among total households.

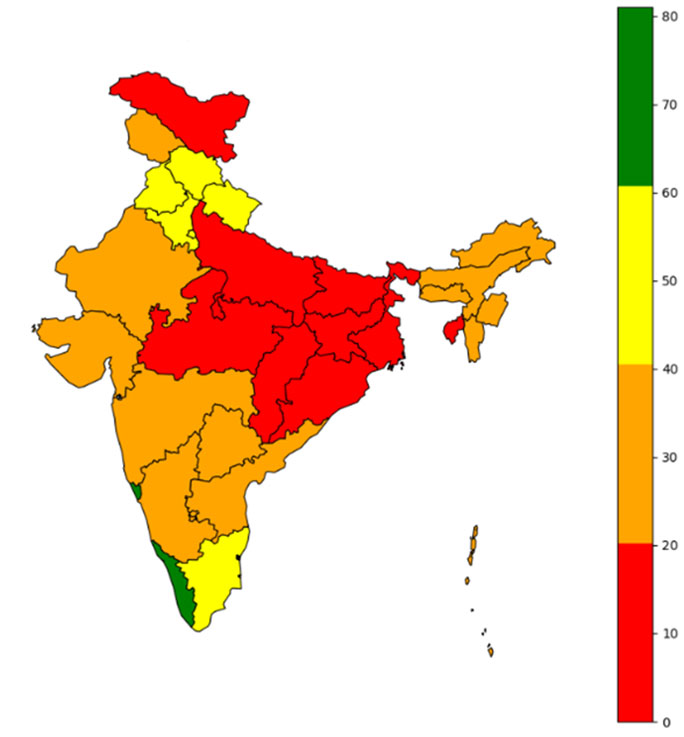

Figure 6b. Digital literacy across states and UTs, rural areas (%)

Source: NSS data; authors’ calculations.

Note: Percentage here indicates percentage of digitally literate households among total households.

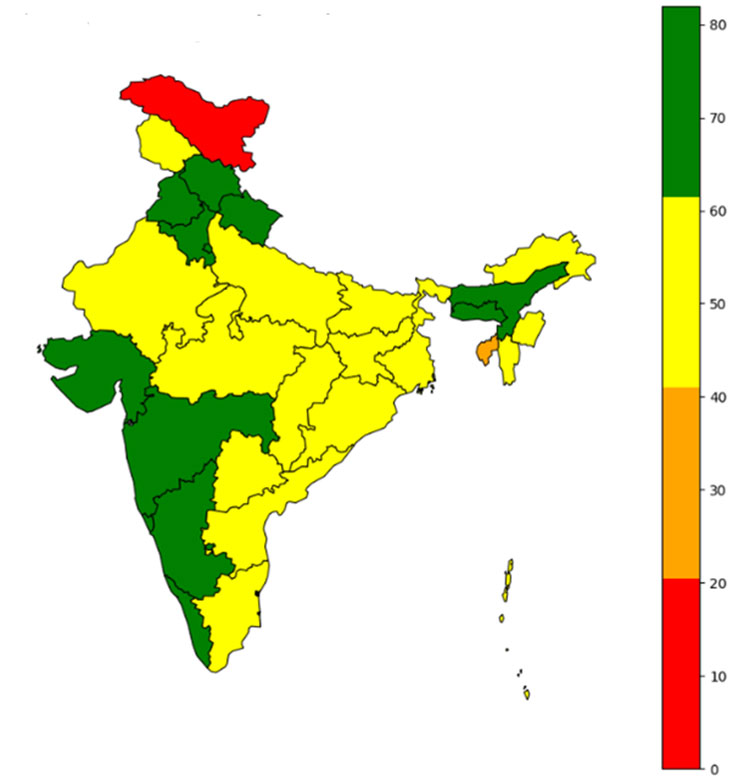

Figure 6c. Digital literacy across states and UTs, urban areas (%)

Source: NSS data; authors’ calculations.

Note: Percentage here indicates percentage of digitally literate households among total households.

Goa and Kerala are the only states that have achieved more than 70% digital literacy at the household level and this is due to the various initiatives undertaken by the state governments over the years. In 2002, the state government of Kerala launched the forward-looking Akshaya project with the aim to make at least one person in each household computer-literate in the Malappuram district of Kerala. The success of the project made Malappuram the first e-literate district3 in India and Akshaya a state-wide endeavour. Numerous other initiatives were also undertaken by the Kerala government, such as the IT@School initiative4 (now known as KITE (Kerala Infrastructure and Technology for Education)), which was launched in 2001 to make school students digitally literate, Information Kerala Mission,5 and Kerala State IT Mission.6 On the other hand, the state government of Goa signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Google India in 2016, to promote digital literacy and drive digital transformation across the state.

The Department of Administrative Reforms under the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, conducted a National e-Governance Service Delivery Assessment in 2019, for initiatives taken by state governments with respect to digital provision of public services. State portals were assessed on the basis of accessibility, content availability, ease of use, and information security and privacy. Kerala and Goa were ranked 1st and 2nd, respectively.

Upskilling India through PMGDISHA

Recognising the urgency to upskill rural India and to bridge the digital divide across rural and urban India, the Government of India launched the PMGDISHA scheme in 2017. This is the world’s largest digital literacy programme with a target of making 60 million people in rural areas digitally literate, involving 40% of rural households with one member per household being trained under the programme. The objective of the scheme is to provide 20 hours of basic training on digital devices and the internet, and how to use these tools to avail government-enabled e-services with a special focus on cashless transactions. Till date, approximately 2.76 crore candidates have been certified as digitally literate under PMGDISHA.

While the PMGDISHA scheme is beneficial for introducing more people to the digital world, the connection with technology would be more long-lasting if the scheme expands its objective to enhance livelihood of beneficiaries through usage of technology. This can be achieved by launching targetted interventions for various beneficiary groups. For example, farmers in India incur huge losses due to unavailability of accurate and timely information regarding weather trends, sustainable farming techniques, and markets. Access to and use of digital tools would help farmers make more informed choices in terms of agricultural practices. This would also be an important step towards mainstreaming ‘digital agriculture’. Along these lines, the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) along with Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Veterinary Education and Research (RIVER) Puducherry launched a Farmers’ Digital Literacy Centre in early 2020 to enhance digital literacy among farmers and spread awareness about sustainable farming techniques. Setting up such centres across the country or utilising existing infrastructure like Common Service Centres (CSCs), school IT labs, Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) etc., to train farmers in the use of digital technology, is a crucial step towards upskilling the agricultural workforce.

Another important aspect is user-centricity – products must be designed considering the capabilities and needs of the end user. For example, if a mobile phone application is being developed to help in the dissemination of information to farmers, it must be taken into consideration that a large number of farmers in India are still not literate. Considering this, innovative ways of communicating instructions through images, audio, and video can be adopted instead of text. Appropriately designed tools must be an integral part of the development of such digital products. The government should revamp existing portals and applications such as e-NAM (National Agriculture Market), to increase their acceptance and usage by a wider set of beneficiaries.

Lastly, the current targets of PMGDISHA are set uniformly across the country without taking into account differences in the baseline digital literacy levels. Goa, Kerala, Chandigarh, and Lakshadweep already have digital literacy levels exceeding 70%, while PMGDISHA target is to make 30% of households from each state/UT digitally literate. On other hand, many Northeast and BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh) states have digital literacy below 30%. There is an urgent need for revisions in target-setting based on available data.

The current state of digital literacy in India clearly indicates that to achieve the goal of ‘leaving no one behind’ in the digital world, it is not only crucial to ensure better connectivity through the development of telecom infrastructure but it is also equally important to build skillsets amongst the Indian population to be able to make the best use of this infrastructure.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- This indicates that people in urban India may have more than one internet subscription per person.

- If the consumption values of the various households are listed in ascending order, the bottom quartile would refer to the bottom 25% of households in terms of their consumption.

- E-literate implies that at least one person in every family is computer literate in that district.

- KITE (formerly the IT@School Project) is a special purpose vehicle company of the education department of the state of Kerala. It aims to provide Information and Communication Technology support to schools as well as higher education institutions.

- The Information Kerala Mission is an autonomous institution under the local self-government department of the Kerala. It aims to computerise and network 1,209 local self-government institutions in Kerala.

- The Kerala State IT Mission operates under the Department of Electronics and Information Technology of Kerala. It provides techno-managerial support to all the e-Governance initiatives in the state.

Further Reading

- Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (2019), ‘Unit Level data & Report on NSS 75th Round for Schedule- 25.2 (July 2017-June 2018), Social Consumption: Education’, Government of India.

- National e-Governance Service Delivery Assessment (2019), ‘2019 NESDA Final Report’, Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances.

23 March, 2021

23 March, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.