The 'Asian miracles' and their industrial policies are often considered as statistical accidents that cannot be replicated. This article argues that we can learn more about sustained growth from these miracles than from the large pool of failures, and that industrial policy is instrumental in achieving sustained growth. Successful policy uses State intervention for early entry into sophisticated sectors, strong export orientation, and fierce competition with strict accountability.

Achieving sustained growth over long periods of time has been an elusive 'holy grail' of macroeconomics. In the past 50 years developing economies have taken different paths. A few – such as the 'Asian miracles' of Hong Kong (China), South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan Province of China – are catching up swiftly with the advanced economies, and some forging ahead. But many are falling behind, to use the terminology of Abramovitz (1986).

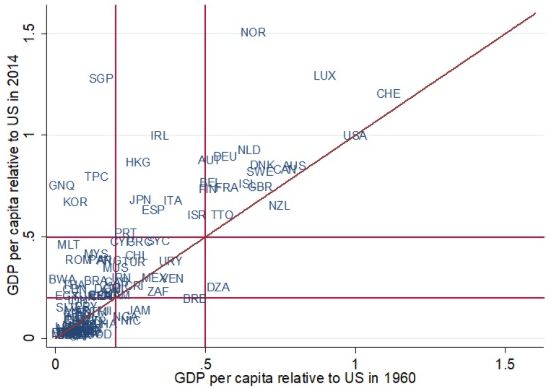

The empirical evidence shows that the odds for poor or middle-income countries to reach high-income status within two generations are very low (Cherif and Hasanov, forthcoming). Between 1960 and 2014, fewer than 10% of economies (16 out of 182 in the sample) reached high-income status. There were three categories of those that made it: Asian miracles, countries that discovered large quantities of oil, and those that benefited from joining the European Union (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Half a century of development

Source: Penn World Tables 9.0 (Feenstra et al.2015).

Note: GDP (gross domestic product) per capita is in 2011 PPP (purchasing power parity) dollars. The thresholds for upper-middle income and high income are 20% and 50% of US GDP per capita, respectively (red lines). The diagonal line indicates no change in relative income levels (with respect to the US level).

We argue (Cherif and Hasanov 2019) that one cannot ignore the pre-eminent role of industrial policy in the development of the Asian miracle countries as well as for Japan, Germany, and the US before them. The industrial policies pursued by the Asian miracles have a lot in common. This suggests that the standard 'growth policy recipe' of tackling only government failures (improving macro-stability, enforcing property rights, providing basic infrastructure and education, and so on) may not be enough to create advanced economies in a short period of time. Instead, recent research suggests that industrial policy may benefit economic development too (Rodrik 2019).

Happy countries are alike

Distilling useful lessons from country experiences is daunting. Without natural experiments it is hard to disentangle the role of policy from luck, or from exogenous factors. Using a stylised model we can show that it is not easy to distinguish between luck and policy in the countries that have diverged.

And with many exogenous factors that affect growth, failures may arise from completely different sources of bad luck. Including these countries may add more noise than signal when we try to establish what determines growth. In contrast, having been spared bad luck, countries that succeeded in catching up possess a lot of valuable information about the common policies that they implemented. To paraphrase Tolstoy: happy economies are all alike; every unhappy economy is unhappy in its own way (Cherif and Hasanov 2019).

Learning more from miracles than failures can be justified empirically as well. The evidence suggests that long-term cross-country growth follows a power law distribution, indicating that important information lies in the tail rather than in the average. This approach contrasts with the standard empirical approach that emphasises averages such as growth regressions. In other words, according to the Nobel laureate in physics Phil Anderson:

“Much of the real world is controlled as much by the tails of distributions as [by] means or averages … by the exceptional not the common place; by the catastrophe, not the steady drip … we need to free ourselves from ‘average’ thinking.” (Ramalingam 2013)

Technology and innovation policy

The lessons of the Asian miracle countries in their pursuit of industrial policy to achieve high-income status suggest three key principles that constitute what we call 'true industrial policy', which can essentially be described as Technology and Innovation Policy (TIP). These principles are:

- State intervention to fix market failures that preclude the emergence of domestic producers in sophisticated industries early on, beyond the initial comparative advantage.

- Export orientation, in contrast to the typical failed industrial policy of the 1960s-1970s, which was mostly import substitution industrialisation (ISI).

- The pursuit of fierce competition both abroad and domestically with strict accountability.

The contrasting cases of Proton in Malaysia and Hyundai in South Korea vividly illustrate these principles at work:

- Proton: The Malaysian government established a national car company, and had an ambitious plan to create a local supplier cluster. The venture was successful in building managerial and engineering skills. But Proton did not manage to export in substantial quantities, and an innovative automotive cluster did not develop (Cherif and Hasanov, forthcoming).

- Hyundai: By contrast, Hyundai succeeded in creating a global brand. A push to export and a bet on several chaebols (massive family-run business conglomerates) to simultaneously develop cars were key elements in its success (Cherif and Hasanov, forthcoming). South Korean automakers vigorously pursued a 'move first, then learn and adjust' approach to exporting.

This drive to export could be attributed to a large extent to State policies (Woo 1991). In exchange for State support given by making loans with low and often negative real interest rates, chaebols had to quickly gain market shares abroad. If they failed to reach export targets, senior management would often be dismissed, and so accountability was strongly enforced. The pressure to export and compete forced Hyundai to increase R&D effort and technology upgrades. By 1991, it had produced its own-design engine, and its first electric car. The State’s bet on several chaebols to develop the auto industry allowed restructuring when needed, and few of them succeeded.

Both the State and the market have their roles when implementing TIP. The State steers labour and capital into activities the market would not necessarily undertake (Cherif et al. 2016a, 2016b). But exposure to competition, market-signal-based decision-making, and an autonomous private sector are also vital.

A three-gear approach to TIP

The State sets the level of its ambition – that is, the level of sophistication of the new sectors and the degree of domestic ownership of technology. It then implements policies while imposing accountability and being able to adapt as conditions change. Ambition, accountability, and adaptability are the 'triple A' of the 'leading hand of the State' (Cherif and Hasanov 2019).

Mediocre growth is not necessarily fatal. It depends on the right policies, and the level of the gear selected (Figure 2).

Low gear: This is a snail crawl approach that results in relatively lower growth, and relative stagnation.

We argue that the standard growth recipe such as improving business environment, institutions, and infrastructure, preserving macro-stability, investing in education, and minimising government interventions constitute only the lowest gear of TIP.

These policies mostly fix government failures, but not necessarily market failures, especially in the development of sophisticated sectors beyond comparative advantage. They may not be sufficient to sustain high long-term growth.

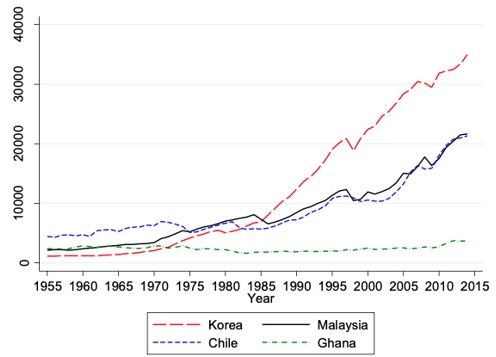

Middle gear: This is a leapfrog approach, mostly relying on attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) in sophisticated industries, or climbing the quality ladder around existing industries (Malaysia and Chile are two examples). This may provide relatively high growth, leading to the middle-income status, but it is unlikely to lead to high-income status within two generations.

Standard policies to attract FDI and develop industries around comparative advantage sectors may result in leapfrogging.

High gear: The Asian miracle countries – the highest gear – use a moonshot approach, in which the aim is to create competitive domestic firms in frontier technologies.

The State intervenes to fix market failures and develop sophisticated sectors, domestic or home-grown technology. It creates conditions for high and sustained long-term growth.

Figure 2. The three gears of development

A technological leap

Overall, the extent of the technological leap to sophisticated industries early, and the extent of the technology creation by domestic firms, determines the success of long-term growth. Countries that manage this process would have a high chance of becoming high-income countries in a relatively brief period. We argue that the Asian miracles implemented these principles, offering clues as to what other countries could do to follow in their footsteps.

Indeed: “If we know what an economic miracle is, we ought to be able to make one”. (Lucas 1993)

Authors' note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

This article first appeared on VoxEU: https://voxeu.org/article/principles-industrial-policy

Further Reading

- Abramovitz, Moses (1986), “Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind”, Journal of Economic History, 46(2): 385-406.

- Cherif, R, F Hasanov and M Zhu (eds.) (2016a), Breaking the Oil Spell: The Gulf Falcons’ Path to Diversification, International Monetary Fund (IMF) Press.

- Cherif, R, F Hasanov and M Zhu (2016b), ‘Breaking the Oil Spell: The Path to Diversification’, VoxEU, 3 September 2016.

- Cherif, R and F Hasanov (2019), ‘The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy’, IMF Working Paper 19/74.

- Cherif, Reda and Faud Hasanov (forthcoming), “The Leap of the Tiger: Escaping the Middle-Income Trap to the Technological Frontier”, Global Policy.

- Feenstra, Robert C, Robert Inklaar and Marcel P Timmer (2015), “The Next Generation of the Penn World Table”, American Economic Review, 105(10):3150-3182.

- Lucas, Robert (1993), “Making a Miracle”, Econometrica,61(2):251-72.

- Ramalingam, B (2013), Aid on the Edge of Chaos: Rethinking International Cooperation in a Complex World, Oxford University Press.

- Rodrik, D (2019), ‘Where Are We in the Economics of Industrial Policy?”, VoxEU, 21 January 2019.

- Woo, M (1991), Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization, Columbia University Press.

31 July, 2019

31 July, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.