In light of India's rapid urbanisation, Rana Hasan looks at various factors which set large cities apart from smaller cities and rural areas: more job opportunities, higher wages, large manufacturing and business sectors, and greater innovation. Although cities already attract workers and firms, he discusses what can be done to make cities even more conducive to job creation. He puts forth policy suggestions, and calls for increased investment in transportation and infrastructure and better coordinated economic and urban planning.

Much structural transformation takes place in and around cities. Cities are not only where the production of manufactured goods and services tends to be most efficient – on account of agglomeration economies1 – but they are also where much consumption takes place. For those two reasons, cities are central to the creation of jobs. The fact that India is urbanising rapidly2 is good news for the country’s jobs challenge. As data indicate, labour market outcomes tend to be better in urban areas as compared to rural areas, and more so in larger cities.3

The importance of urbanisation for meeting India’s jobs challenge

First, not only are wages higher as people move from rural areas to urban areas and from smaller cities to larger cities, but the quality of jobs also improves. Based on data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2018-2019, which allows respondents in urban areas to be distinguished in terms of whether they belong to cities with a population of 1.5 million or more (in 2011), the share of ‘regular’ wage workers in wage and salaried employment was 90.3% in large cities, as compared to 75.6% in small cities and 33.4% in rural areas. Such jobs offer more employment stability and other non-wage benefits than casual wage work. Similarly, larger cities also tend to have a greater share of wage employment in enterprises with 10 or more workers (54.6% in larger cities, 46.8% in smaller cities, and 28.2% in rural areas), a proxy for employment in a formal sector enterprise.

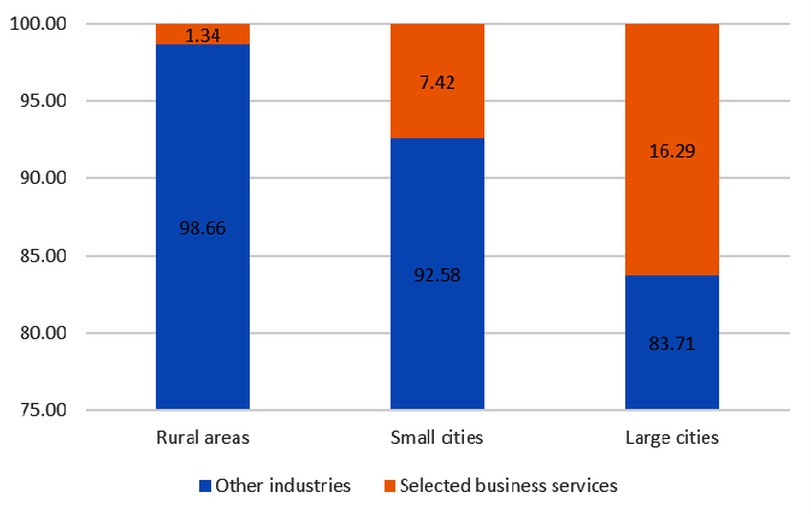

Second, manufacturing and business services – sectors associated with economic dynamism – account for a larger share of employment in urban areas, and large cities within them.4 These sectors accounted for 49% of employment in large cities, compared to 39% in smaller cities, and just 14% in rural areas. Restricting attention to a narrower set of business services where agglomeration economies are likely to be especially important (that is, knowledge-oriented services such as finance, consulting, and IT related services), differences across rural areas and small and large cities remain quite important (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage share of select business services in total employment

More generally, cities offer a wider range of jobs. Examining occupation codes, urban areas create a wide range of jobs in both traditional occupations in manufacturing and services (for example, potters and glass makers, and legal professionals), as well as less traditional ones (for example, computing professionals and associates. and writers and creative or performing artists).

Features of wages in relation to geographical differences

It is useful to examine how wages vary across rural and urban areas using individual level data from the PLFS 2018-2019. Controlling for age, gender, and educational attainment, as well as state, industry and occupation of employment, wage and salaried workers in urban areas on average earn around 17% more than their counterparts in rural areas, while those in large cities earn around 14% more than those in smaller cities.

Employment in a formal firm is associated with better pay regardless of location, though this is a bit more pronounced in urban areas. Importantly, estimates based on the PLFS 2018-2019 indicate that gender bias diminishes as one moves from rural to urban areas, and from smaller to larger cities. Finally, the data suggests larger returns to human capital accumulation in urban areas and large cities within urban areas. These patterns are found in labour force survey data of earlier years as well (Hasan and Molato 2019).

As far as innovation is concerned, India’s larger cities tend to introduce product and process innovations and conduct research and development (R&D) more often than their counterparts in smaller cities. Specifically, geo-coded enterprise survey data on more than 8,000 enterprises and across 207 Indian cities,5 suggests that firms in a city twice as large as another are more likely to engage in product innovation, process innovation, and R&D by 17.5%, 9.9%, and 21.2% respectively (Chen, Hasan and Jiang 2021). Taken together, these findings lend support to the idea that agglomeration economies are important in the Indian context.6

Admittedly, the findings above do not tell us about causality, due to the possibility that unobserved individual and locational characteristics may be important. For example, workers in larger cities may be paid better on account of higher unobserved human capital obtained through access to higher quality education. Similarly, more innovative entrepreneurs may choose to locate in larger cities in order to access a (typically) larger pool of skilled workers and better infrastructure.

However, some attempts to control for potential endogeneity using historic city size suggest that agglomeration effects are indeed present, though their magnitude can diminish dramatically upon the use of an instrumental variable (IV) strategy7 (see Chauvin et al. 2017 and Hasan et al. 2017 on agglomeration effects and wages, and Chen et al. 2020 on the city size-innovation link). The study by Hasan et al. 2017, in particular, finds a rather dramatic reduction in the effects of city size on wages in their IV regressions. This is consistent with the notion that there is scope to realize more fully India’s urbanisation potential by addressing issues related to the provision of urban infrastructure and economic and spatial planning.

Managing cities to harness their jobs potential

A number of researchers have raised concerns about the nature of urbanisation currently underway in the developing world, and its impact on economic growth. For example, Gollin et al. (2016) bring up the case of two cities, Shanghai and Lagos. Both are large cities in countries with similar urbanisation rates. However, it is highly unlikely that their potential to deliver on better economic outcomes for their residents is the same. For example, Shanghai is host to an array of internationally competitive manufacturing sector firms; in contrast, leading firms in Lagos tend to focus on natural resources and products aimed at domestic consumption.

In India’s case, several scholars and studies have noted that the potential of its cities and towns to spur economic activity may not be fully met due to several factors, including limited investment in infrastructure, the prevalence of unsynchronised spatial and economic planning systems, and suboptimal land-use management (McKinsey Global Institute, 2010, Ahluwalia et al. 2014, Mathur 2016). Thus, while India’s cities may continue to grow in terms of population, action must be taken to ensure that they fulfill their potential as engines of growth, and generators of productive and well-paying jobs – good jobs, for short. These are some issues for policymakers to consider, particularly when it comes to the provision of infrastructure. For instance, an inadequate transport network fragments a city’s labour market and diminishes the scope of agglomeration economies. Especially hard hit are lower-income households residing in locations within cities (or in their surroundings) with limited access to fast and cheap public transport (Chen, Go and Jiang 2021).

Investments in improving the transport network have to be complemented by appropriate land use regulations and building by-laws. Restrictions on building height, for example, can constrain the supply of commercial and residential land, encourage urban sprawl, reduce job density, and undercut the economic benefits of investments in public transport such as metro rail and bus rapid transit systems (Chen and Hasan 2022).

Conclusion

Cities need to be proactively managed if they are to be good places for firms and workers to be located in. In India, as is common elsewhere, a host of public agencies provide ‘public’ inputs that are crucial in the production of private goods and services (for example, transport, uninterrupted power, access to appropriately located land, and the social amenities necessary for workers and their families). Coordinating the delivery of these various inputs is not easy, and local government officials in many countries play an important role in trying to ensure that their cities are attractive locations for firms and workers. In the Indian context, where local government officials are less directly involved in the provision of a vibrant ecosystem for production (Asian Development Bank, 2019), a governance framework that incentivises different public agencies to contribute toward a good investment climate at the city level is needed. Tackling these issues, though challenging, is sure to have a very large payoff in meeting India’s jobs challenge.

The author is grateful to Kriti Jain and Shalini Mittal for the analysis of PLFS 2018-2019 data. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

This post is the third in a six-part series on 'The good jobs challenge in India'.

Notes:

- Agglomeration economies refer to the economic benefits that arise when firms and workers are located and operate in close physical proximity. They arise because larger, denser locations make it more likely that workers will get jobs that are a good fit; individuals and organisation will exchange ideas and knowledge; and resources are more efficiently shared. See Duranton and Puga (2004) for details on these three mechanisms, more conveniently referred to as matching, learning, and sharing.

- According to the Census of India, the share of India’s population residing in urban areas increased from 20% in 1971 to 31% in 2011, representing an urban population of 377 million. Projections by the United Nations suggest that the country will add another 400 million people to its cities by 2050 and have half its population residing in urban areas.

- One exception is unemployment rates, which are lower in rural areas (5.02% compared to 7.23% in urban areas). Focusing on urban areas, cities with less than 1.5 million residents had slightly lower unemployment rates than larger cities (7.19% compared to 7.32%) (calculated using PLFS 2018-2019 micro records).

- Business services as defined here includes transport and storage; information and communication; financial and insurance activities; real estate activities; professional, scientific and technical activities; and administrative and support service activities.

- Geocoded enterprise survey data are from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

- To capture the productivity advantage of agglomeration, it is sufficient to show that firms pay higher nominal wages for workers with similar characteristics. This is because nominal wages reflect how much more firms are willing to pay in bigger cities to comparable workers (De La Roca and Puga 2017).

- Instrumental variables are used in empirical analysis to address endogeneity concerns. An instrument is an additional factor that allows us to see the true causal relationship between the explanatory factor and the outcome of interest. It is correlated with the explanatory factor but does not directly affect the outcome of interest.

Further Reading

- Ahluwalia, IJ, R Kanbur and PK Mohanty (2014), ‘Challenges of Urbanisation in India: An Overview,’ in IJ Ahluwalia, R Kanbur and PK Mohanty (eds.), Urbanisation in India: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Way Forward.

- Asian Development Bank (2019), ‘Asian Development Outlook 2019 Update: Fostering Growth and Inclusion in Asia’s Cities’, ADB.

- Chauvin, Juan Pablo, Edward Glaeser, Yueran Ma and Kristina Tobio (2017), “What is different about urbanization in rich and poor countries? Cities in Brazil, China, India and the United States”, Journal of Urban Economics, 98: 17-49.

- Chen, L and R Hasan (2022), ‘In India, Capturing the Value of Land Near Metro Stations Is Critical’, Asian Development Blog, 5 April.

- Chen, Liming, Rana Hasan and Yi Jiang (2021), “Urban Agglomeration and Firm Innovation: Evidence from Asia”, The World Bank Economic Review, 36(2): 533-558.

- Chen, L, E Go and Y Jiang (2021), ‘Accessibility Analysis of the South Commuter Railway Project of the Philippines’, ADB Briefs, No. 185. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF2101314-2

- Chen, L, R Hasan and Y Jiang (2020), ‘Urban Agglomeration and Firm Innovation: Evidence from Asia’, Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, No. 616.

- De La Roca, Jorge and Diego Puga (2017), “Learning by Working in Big Cities”, The Review of Economic Studies,84(1(298)): 106-42.

- Duranton, G and D Puga (2004), ‘Micro-Foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies’, in V Henderson and JF Thisse (eds.), Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics. Vol. 4.

- Gollin, Douglas, Remi Jedwab and Dietrick Vollrath (2016), “Urbanization With and Without Industrialization”, Journal of Economic Growth, 21(1): 35-70. Available here.

- Hasan Rana and Rhea Molato (2019), “Wages Over the Course of Structural Transformation: Evidence from India”, Asian Development Review, 36(2): 1-28.

- Hasan Rana, Yi Jiang and Radine Michelle Rafols (2017), “Urban Agglomeration Effects in India: Evidence from Town-Level Data”, Asian Development Review, 34(2): 201-228.

- Mathur, OP (2016), Cities and the New Economic Vibrancy, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

14 September, 2022

14 September, 2022

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.