In February 2021, the Indian government stated that it may allow firms the flexibility of having a four-day work week, while retaining the norm of 48 hours of work per week. In this post, Koustav Majumdar assesses the potential impacts of such a policy change on women and their workforce participation – given that women are known to disproportionately bear the burden of domestic work on a day-to-day basis.

In the last few months, there has been a lot of buzz in the media regarding the possibility of allowing the flexibility of having a four-day work week in in India. In late 2019, Microsoft announced that a pilot project of having a four-day work week for their employees in Japan not only increased satisfaction among the workers, but improved productivity as well. Ever since then, there has been growing interest in this proposition across firms and countries. When the Covid-19 pandemic brought the world to a halt and remote working became a norm for most people in the tertiary sector, it triggered fundamental debates around how and where we work. In February 2021, the Labour Secretary of India, Apurva Chandra told reporters that the government might allow firms the flexibility of having a four-day work week, albeit keeping the 48-hours of work a week “sacrosanct”. This effectively means that while the work week contracts to four days, the work day increases to 12 hours.

In most advanced economies, a five-day work week consisting of 40 hours a week or eight hours a day, has been the norm for decades now. However, in India, a work week in the organised sector can last for a maximum of 48 to 56 hours, depending on the industry of work. This is essentially due to the lower rate of productivity among workers overall as compared to those in the advanced economies (International Labour Organization, 2020). Due to the prevalence of long working hours, recent studies have indicated that Indian workers constitute one of the most overworked workforces in the world. Given such dire working conditions, a reduction to a four-day work week can be seen as a welcome move. But there is a catch.

Women and the four-day work week

Take the example of Anita. She is a 35-year-old mother of two children who works in a clerical position at a private firm in Kolkata. Every morning she wakes up at 6 am and gets her children ready for school. She prepares breakfast and lunch for all family members. She then leaves for her work by 9 am and returns home after 6 pm in the evening. After returning she prepares evening snacks and dinner for her family while overseeing her children’s homework. After finishing her household chores for the day, she goes to bed at around 11 pm, only to wake up the next day and repeat all of it. If her company decides to shift to a four-day work week by increasing the daily hours of work, will she be able to manage both her professional and domestic commitments?

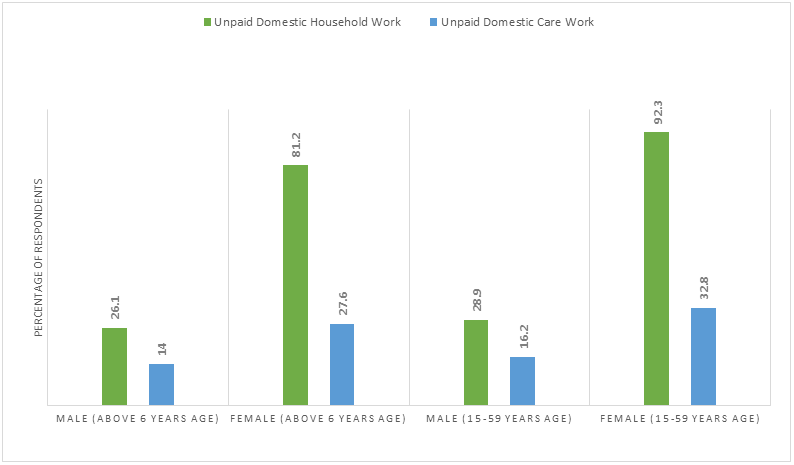

Anita is just one of the many women in India who have to balance their daily schedule between office work and domestic responsibilities, what is often called paid and unpaid work in labour studies. The recent report of the National Statistical Office on time use in India, presents the findings of their year-long survey of almost 139,000 households across India covering over 447,000 persons above the age of six (NSO, 2020). The survey findings were not unexpected, but it helps us to connect the anecdotal stories to actual statistics. As per the report, around 81.2% of women participated in unpaid domestic activities for household members such as cooking, cleaning or shopping for household goods as compared to just 26.1% of men. Further, 27.6% of women participated in unpaid domestic care work as compared to only 14% of men. Among those between the ages of 15 and 59, 92.3% women participated in unpaid domestic household work and 32.8% participated in unpaid domestic care work, compared to just 28.9% and 16.2% men respectively.

Figure 1. Participation rate in unpaid domestic work, females vs. males

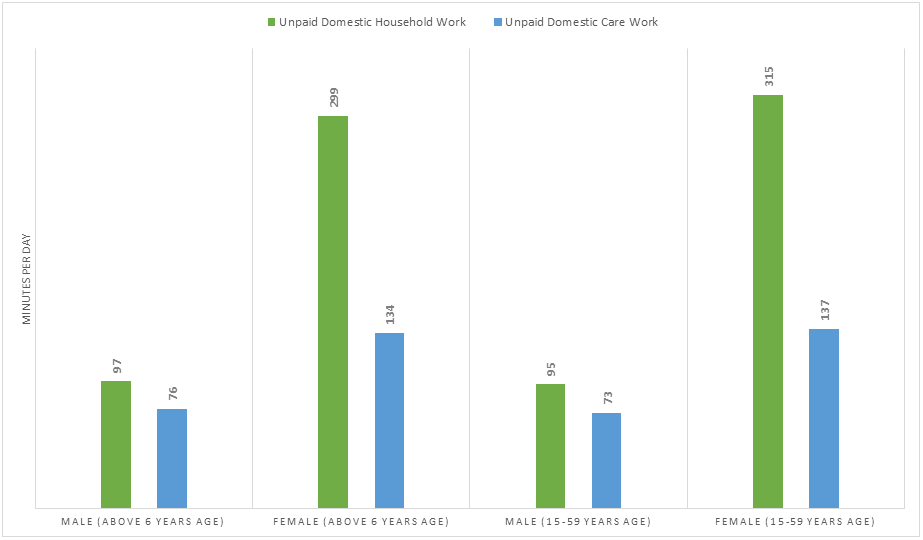

Not only is the male participation rate in unpaid domestic work low, but even among those participating, the amount of time spent on such activities is significantly lower compared to women. Among women who participated in unpaid domestic household work, the time spent in such activities per day on average was 299 minutes (approximately five hours) versus an average of 97 minutes (just over one and a half hours) among the men who participated. In case of unpaid domestic care work, the amount of time women spent on such activities per day on average was 134 minutes (approximately two hours and 15 minutes) compared to the average of 76 minutes (just over an hour and 15 minutes) among men who participated. Among those between the ages of 15 and 59, these figures are higher in the case of women (relative to all women) and lower in the case of men (relative to all men).

Figure 2. Average time spent daily on unpaid domestic work, females vs. males

From the above data it is clear that female household members spend more than 7 hours daily, on average, on unpaid household activities. Although the time spent on unpaid domestic work among women working full-time in the tertiary sector would expectedly be lower than seven hours a day on average, the key point is that the burden of unpaid domestic work essentially falls on women. For example, a 2017 study by researchers from the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex revealed that in Indian households, the girls were the main secondary caregivers, including sibling care, rather than the adult males of the family. In such conditions an increase in daily working hours by 2.5 to three hours can have a significant impact on women’s employment. Women from lower income households who cannot afford paid domestic help could be worse-off since they would have to cut-back on self-care activities, particularly sleep, in order to keep their jobs and continue to do household chores, which would in turn affect their health. It could also create an additional barrier for women from conservative households to enter the job market. Moreover, a 12-hour workday would typically end between 9 and 10 pm, or start very early, which could present issues of transportation and safety for many people, especially women.

Concluding remarks

A four-day work week is still a far-fetched notion in India, and the government – even in preliminary reflections on the issue – has assured that it would not be the norm but just an option for firms. Given the declining female labour force participation in India, from 30.3% in 1990 to 20.3% in 2020, the implementation of a four-day work week could present new challenges as discussed above. On the other hand, it is possible that participation in unpaid domestic activities among men may increase, with the burden being shared more equitably across genders. What is clear is that before the implementation of such norms, there must be extensive discussion and debate regarding all potential pros and cons. Can the four-day work week bring about a much-needed social change or would it just make the glass ceiling higher for women?

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Further Reading

- International Labour Organization (2020), ‘Global wage report 2020-21’.

- National Statistical Office (2020), ‘Time Use in India - 2019’, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

- Zaidi, M, S Chigateri, D Chopra, and K Roelen (2017), ‘‘My work never ends’: Women’s experiences of balancing unpaid care work and paid work through WEE programming in India’, IDS Working Paper, Vol. 2017, No. 494.

20 April, 2021

20 April, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.