Higher-powered incentives are generally believed to increase worker productivity. In the context of an Indian tea plantation, this column examines a contract change wherein baseline wages were increased and incentive piece rates were lowered or kept unchanged. It finds that output increased by 20-80% in the following month but fell to original levels thereafter. Possible explanations for the observed impact are explored.

A traditional consensus in economics is that money talks, or at least it talks as loudly as anything else. Of course, no one regards this as some implacable law: we all know that people are tempered by altruism, morality or notions of justice. But the view certainly dominates sub-fields of economics such as contract theory: within the employer-employee relationship, higher-powered incentives are generally believed to increase worker productivity.

Like all traditions, this one has been challenged. A recent literature in behavioural economics emphasises social incentives. There is, for instance, the view that individuals are social (and socially-motivated) agents, so that “extrinsic incentives” linking performance to money may crowd out “intrinsic incentives” to exert effort (Gneezy and Rustichini 2000, Gneezy, Meier and Rey-Biel 2011). Numerous experimental studies have also emphasised that individuals may also respond positively to (unconditional) gift giving (Bellemare and Shearer 2009).

"In a recent paper published in the American Economic Review (Jayaraman, Ray and Véricourt 2016), we study these two views empirically.

Contract change in an Indian tea plantation

Our setting is a tea plantation owned by a large Indian tea producer, in a region where tea is a dominant source of low-skilled employment. While the producer is one of several local producers in this region, the plantation is large. It covers several hundred fields, and employs roughly 2,000 workers. The fields comprise rows of tea bushes, which are plucked individually by hand or by metal shears according to a pre-determined schedule. Workers work in ‘gangs’ of 20-40, under supervision.

Workers - who may be either permanently employed or just temporarily hired for the plucking season - have identical individual wage contracts, which consist of a daily fixed wage, plus additional piece rates per kilogram of tea-leaf plucked. Regular tabs are kept on the weight of plucked leaf, and wages are calculated daily and paid at month-end.

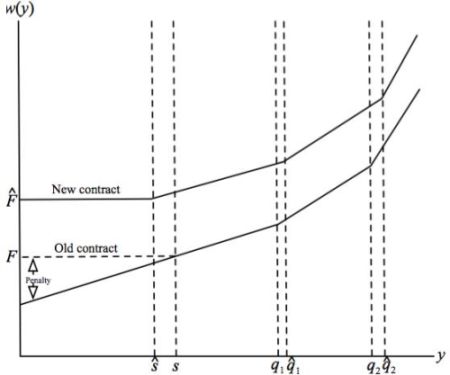

In the tea industry, by popular convention, wage contracts are renegotiated every three years and apply to all plantations in the locality. In the case of our plantation, 20 unions (covering about 10,000 workers) and plantation owners bargained over a new contract in mid-2008. As it turned out, there was a government-mandated increase in the fixed daily wage by over 30%. Owners understandably resisted this increase, but their petition was dismissed by the state high court. In order to counteract the fixed wage increase, planters flattened the piece rate. Figure 1 describes the increasing piece-wise linear contract under the old and the new wage contract, w, as a function of daily output (y). Note that the new contract essentially consisted of a shift up, and a flattening of wages. In summary, we have the perfect stage to examine the effects of a change in monetary incentives, within an employer-employee setting.

Figure 1. Tea plantation wage contract: Old vs. new

Notes: (i) F and Fˆ are the fixed daily wages under the old and new contract respectively (ii) Under the new contract output thresholds corresponding to higher piece rates have shifted from q1 to qˆ1 and from q2 to qˆ2 (iii) The wage loss below the standard s in the old contract was worded as a penalty.

Notes: (i) F and Fˆ are the fixed daily wages under the old and new contract respectively (ii) Under the new contract output thresholds corresponding to higher piece rates have shifted from q1 to qˆ1 and from q2 to qˆ2 (iii) The wage loss below the standard s in the old contract was worded as a penalty. Immediate impact

Classical incentive theory makes a clear prediction for what should happen to productivity (daily output per worker) after this contract change. Productivity should fall, or at least not increase. The reason is simple: flatter piece rates means that the monetary rewards to effort decrease and as a result, workers should put in less effort and produce less output.

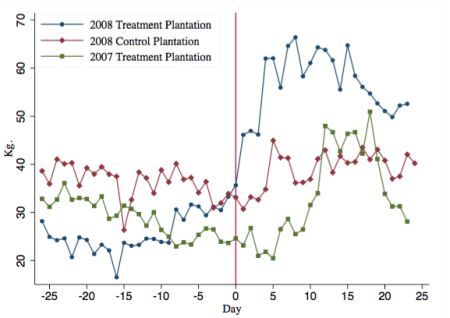

What happened in the next month was unexpected and quite dramatic. Output increased by 20-80%, the wide range of possibilities coming from the particular controls we include and the counterfactuals we use. You can see this in the raw data. Figure 2 shows the striking increase in daily output under the new contract (after “Day 0”) in the study plantation (‘treatment plantation’) in 2008 (the year of the contract change), relative to two counterfactuals where there was no contract change during this calendar period: a plantation in a nearby geographic location which follows a different three-year contract renegotiation schedule (‘control plantation’), and the study plantation in the previous year (2007).

Figure 2. Comparing output under new contract vs. counterfactuals of no contract change

There are, of course, a number of obvious explanations that we will need to address. First, the contract change occurs near the start of the plucking season, so the subsequent increase could represent a seasonal effect. Indeed, the structure of the contracts reflects this by imposing an increase of about 20% in “minimum standard” (s in Figure 1) starting September, in both 2007 and 2008. That number pretty much matches the percentage increase in output we see in the ‘treatment plantation’ in 2007 and the ‘control plantation’ in 2008. But it is nowhere near the 75% we see in Figure 1 in the September following the contract change in 2008. Second, the increase could have reflected a change in participation rates but in fact, we see no such change in the data. Third, it could reflect a shift in technology, with more workers using shears in the post-contract change period. However, the jump in productivity is present for each of the two technologies: hand and shears. Finally, there could have been local changes in weather patterns, specific to the plantation at the time of the contract change.

Even after controlling for potentially confounding factors such as daily rainfall, time-varying technologies (shear vs. hand), the intensity with which the field has been harvested in the recent past, etc., we still find a net increase in output of at least 20% over and above the control plantations (and generally more, depending on the precise composition of controls and counterfactuals). By any standard, this is a striking increase. It is also clearly not consistent with the traditional theory which - as we’ve observed - unambiguously predicts that productivity should weakly decline under the new contract.

The obvious suspects aside, five other classical explanations could account for the increase we see. First, dynamic incentives may be operative, as opposed to the static incentives provided by piece rates. That is, workers could have been fired for sub-standard performance. After all, given the better terms of the new contract, they would presumably have more to lose. This explanation doesn’t hold water because, as it turns out, the temporary workers on the plantation are less responsive to the contract change than permanent workers, who cannot be fired. Second, supervisors may have exerted more pressure on workers. This channel is a possibility: we show that it could account for up to a quarter of the increase we see. Third, output was unusually low in the first few weeks of observation for the treatment plantation, so one argument is that the increase we observe just reflects ‘saving up’ on leaves and then chopping them off in larger quantities in the period after the contract change. But this argument is not valid: tea leaves become useless if they are not plucked in regular (shorter) intervals. Fourth, one might hazard the guess that this is a learning effect of some kind; near-impossible, given that most of the workers in this plantation have been plucking tea for decades. Finally, the increased productivity could be the result of improved nutrition. But wages are paid only at the end of the month -long after the observed increase in productivity - and credit markets are highly imperfect.

This process of systematic elimination pushes us to conclude that what we see in the immediate aftermath of the contract change is indeed a ‘behavioural’ response. The data do not allow us to unearth the precise behavioural mechanism, but given the long tenure of workers at this plantation and the close relationship they share with management, it seems likely that gratitude and reciprocity play a part here.

Many ‘behavioural’ research papers on incentives stop there. An experiment is run, typically in a lab, sometimes in a somewhat contrived work setting (example, students are ‘hired’ to stuff envelopes), effort responses to various incentives are measured and researchers conclude that behaviours contradict the predictions of a classical model, but are consistent with the predictions of a behavioural model. Workers care about fairness. They respond to generosity. They engage in reciprocal gift giving. At this point, the satisfied behavioural economist typically packs his bags and goes home.

Impact over a longer period

Indeed, we would have probably come to a similar conclusion had we terminated our analysis a month into the new contract. However, we were in the fortunate position of having data four months into the contract change, up until the end of the plucking season. The picture that emerges through these later months is rather different. Starting around the second month, a decline sets in until, four months after the contract change, output returns to pre-change levels.

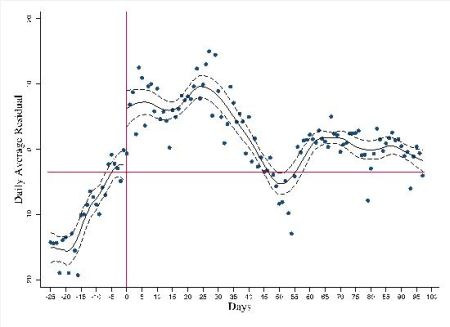

Figure 3. Impact on output over four months after contract change

Figure 3 above extends the analysis to four months after the contract change. It plots output residuals relative to the pre-contract period, after accounting for rainfall and other controls. The horizontal line denotes the average residual right at the start of the contract in 2008. This panel then plots the daily residuals to Month 4. It shows that the Month 1 productivity response persists through the second half of Month 2, but then tapers off until, by the end of Month 4, output retreats to the levels in the week before the contract change.

This reversal is equally dramatic, as the entire process appears to complete an eventful but ultimately ephemeral round-trip. What, then, accounts for the long-run productivity response to the contract change? The answer, as it turns out, is: a very simple classical model with static incentives. Structural estimates using this simple model show that in the short run it is way off the mark. But by the end of Month 4, it does a remarkably good job of predicting the productivity response to the new contract.

Behavioural economics: Time horizon matters

Economists have emphasised that individuals may have both intrinsic and extrinsic motives underlying their actions. Blood donation is a canonical example. People probably donate blood because helping their fellow human beings makes them feel good about themselves. They are intrinsically motivated to donate blood. Placing an extrinsic reward on this activity by paying them for it may well crowd out this intrinsic motivation and (particularly if the price is too low) drive down blood donations. Our situation is a bit different. Here, the underlying relationship is paid employment: people work for an extrinsic reward. Giving them a generous wage hike may well have stirred intrinsic motivations founded in gratitude or reciprocity among workers, all of which translated into more effort and more output. But ultimately, these pro-social motives do not hold sway.

Behavioural economics has captured public attention in recent years, and for good reason. One doesn’t have to look far to realise that human beings are not always rational and that they may have social preferences. It would be foolish to ignore this possibility. Indeed, our own results show that behavioural considerations do matter, at least in the short run. The problem is that much of the empirical evidence we have in behavioural economics looks exclusively at short-run outcomes. To assume that these short-run responses also apply to the long run is equally problematic. At the end of the day, the ‘right’ model for prediction will depend on whether you are interested in the short run or the long run. But before we rubbish workhorse classical models and hurriedly classify important economic phenomena as fundamentally ‘behavioural’, we should at least study these phenomena over a longer period of time.

Further Reading

- Bellemare, Charles and Bruce Shearer (2009), “Gift Giving and Worker Productivity: Evidence from a Firm-Level Experiment”, Games and Economic Behavior, 67(1): 233–44. Available here.

- Gneezy, Uri and Aldo Rustichini (2000), “Pay Enough or Don’t Pay at All”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3): 791–810. Available here.

- Gneezy, Uri, Stephan Meier and Pedro Rey-Biel (2011), “When and Why Incentives (Don’t) Work to Modify Behavior”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4): 191–210. Available here.

- Jayaraman, Rajshri, Debraj Ray and Francis de Véricourt (2016), “Anatomy of a Contract Change”, American Economic Review, 106(2): 316-358. Available here.

08 August, 2016

08 August, 2016

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.