The need for financial literacy and its importance for financial inclusion have been widely recognised. Based on various research studies on financial literacy initiatives, this column outlines financial services’ needs of a poor household at various stages of its life cycle. It contends that customising financial literacy programmes according to the stage of life of targeted individuals is crucial for their effectiveness.

The need for financial literacy and its importance for financial inclusion have been acknowledged by all possible stakeholders - policymakers, bankers, practitioners, researchers and academics – across the globe. Various financial literacy programmes have thus been implemented by concerned institutions, with a lot of them being unique in their approach and delivery mechanisms. For instance, programmes have been customised to suit the requirements of students, microfinance clients, slum dwellers, bank clients etc. Some programmes have a particular focus such as a specific financial product, developing saving habit among target group, customer protection, business management, and so on, while others are more general and deal with money management skills, advocating healthy financial practices etc. Varied techniques such as videos, stories, activities, comic books etc. are used, along with traditional methods of classroom training. Banks like Punjab National Bank and State Bank of India have also begun setting up ‘financial literacy and credit counselling centres’ that people can go to for gathering requisite information.

While a lot of experimentation has been done in the realm of financial literacy, it is difficult to point to one standardised method or approach that works best in all scenarios with all kinds of target populations. Although this could be attributed to the lack of a standard definition or measurement tool, it is also a result of India’s diversity in terms of language, caste, culture etc. Hence, it is challenging to design a product that ‘fits all’ sections of the population equally well.

Financial services’ needs at different stages of a poor household’s life cycle

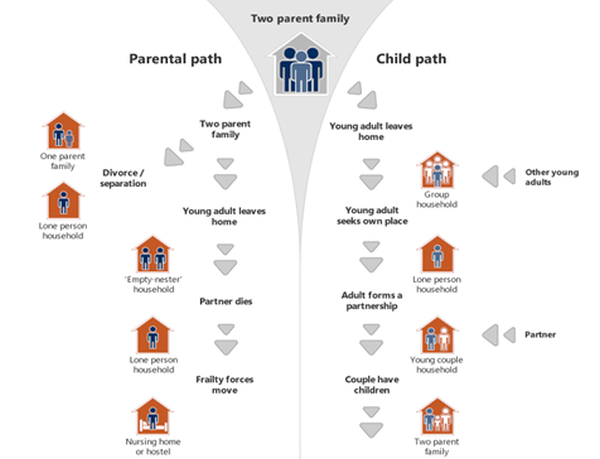

Going back to the drawing board, it is important to work with the premise that financial services’ needs of an individual vary primarily by age. While these also depend on financial status, social status and other factors, let us keep that constant and consider the life cycle of a poor household (primary target beneficiaries of financial literacy programmes). Children initially stay with parents and go to school. Following studies, they may move out of the parents’ house and begin to live on their own (or with friends/ housemates) and earn their own living. They then get married, form a couple and start their own family. By this stage, the parents are old, with reduced income levels because of lower physical capacity to work. They seek support from their children who have just been endowed with new responsibilities of a family, with children of their own to raise. The cycle continues with these children getting educated, moving out to find a job and then eventually raising their own families, while assisting their parents.

Figure 1. Life cycle of an individual/ household

This simple story of the household involves an exchange of dependency and responsibilities at each stage. Considering just the financial services’ needs of the household over its life cycle, we see that they are very specific to the stage that the household or individual is in at a given point of time. For instance, as a school going kid (in his/ her teenage), an individual might require know-how of savings so that he/ she can save pocket money or scholarship and utilise it effectively. A young person who has just started working and receiving a salary, would require a banking service, complex investment products (given that youth are more inclined to risk-taking and are open to experimentation) and remittance services that would enable him/ her to send a portion of earnings to parents who are not able to do as much physical labour as they could earlier. As time progresses and the individual gets married and starts a family, he/ she is required to think about safer financial products and longer term investments. His/ her dependency ratio is highest at this point – both children and parents are dependent on the individual. As the individual becomes older, simple banking services are required to access remittances transferred by children, and welfare transfers from the government.

Considering all of these specific financial services’ requirements at various junctures in life, four teachable moments can be identified: school-going child (grown up enough to understand money and saving), youth (stepping into employment), middle-aged (married, and starting a family), and old age. These are the specific stages of transition, when the need for financial products/ services takes a leap and it is crucial to make the right financial decisions. Thus, these moments are best suited for receiving and benefitting from customised money management advice.

Customising financial literacy modules based on stages of life

After establishing the ‘what’ and ‘when’ of financial literacy, it is important to understand the ‘how’ of it. As an individual ages, a lot of psychological and behavioural attributes change, as per the social, political or economic environment. The three prime attributes that notably differ with each of the four stages of life and should be thought through well while designing any education module, but especially a financial literacy module, are: attention span, cognitive ability, and general points of attraction.

Table 1 maps the four teachable moments with the associated attributes, along with the work that has been done so far in terms of implementation of financial literacy initiatives and assessment of the impact of the initiatives. Analysing each of the stages independently would throw light on the way forward in designing financial literacy modules. A cross analysis of these, however, highlights the fact that there is little or no commonality among them and each is required to be taught with different instruments varying in content, delivery mechanism and need for innovation.

Table 1. Mapping teachable moments with attributes and financial literacy methods

| Stages | Attributes | Methods | ||

| Attention span/ Cognitive ability | General points of attraction | Tried methods | Evidence of impact | |

| School-going kids |

|

|

|

No research has been done |

| Youth (stepping into employment) |

|

|

|

|

| Adults/ middle-aged |

|

|

|

|

| Old |

|

|

|

|

Note: This table is based on findings and learning from various studies conducted by IFMR-LEAD on the subject of financial literacy (http://ifmrlead.org/evaluating-finos-financial-literacy-education-program/ ; http://ifmrlead.org/the-role-of-financial-access-knowledge-and-service-delivery-in-savings-behavior-and-welfare-in-bihar/ ;

To elaborate, the cognitive ability of a person starts developing when he/she starts going to school. At this stage, an individual is immature with low or no understanding of emotions and concept of time. They take time to solve problems that require abstract thinking. They are usually attracted to things that are colourful, and are significantly influenced by games. ‘Learning by doing’ is the mantra that drives childhood. Kids these days are also involved in social networking. Although no research has been done to study the impact of any kind of financial literacy training on school-going kids, instruments like comic books and concept of saving in a piggy bank seem promising, given the attributes of their age.

Similarly, a youngster just stepping into employment is characterised by good sensory abilities and memory skills. Reasoning and logical thinking are fully developed. At this stage, an individual is highly ambitious and feels a need for independence, self-reliance and freedom from authority. Acceptance among peers is equally essential. Keeping these in mind, some teaching mechanisms like money games, simulation games and soap operas have been designed and adopted globally, yielding positive results on financial behaviour of the youth (Tufano et al 2010).

Skipping to the last teachable moment, no financial literacy programme focuses on the elderly, and the research on developing a module for this age group has also been nil. There have, however, been government initiatives such as the Adult Literacy Programme that could be used to impart financial education. For such a financial literacy programme to be designed, attributes like divided attention, loss of recent memory and slower response to sensory stimulation need to be considered. Also, their parental experience and affinity to religious events and activities could be leveraged upon. Occasions of interest to this age group should be used to bring them together and learning should be derived from discussions of their experiences in life.

In contrast to the work in the sphere of financial literacy that has been done with school-going kids, youth and elderly, various interventions have been developed and implemented for middle-aged people. This segment of the population is intellectually sharp but with a relatively slower reaction time as compared to youngsters. People in this bracket take time to learn new things but their ability to do so does not change. They mostly understand things that they can relate to their lives, families, jobs, adversities etc. A lot of innovative methods have been adopted to teach them best financial practices, some aligning with their attributes and others ignoring them. Most of the studies that have been conducted so far with this particular group illustrate an impact on financial awareness and knowledge of the participants but limited effect on their financial behaviour, which in fact, is the key intended outcome of any financial literacy programme (Cole et al. 2009, Cole and Shastry 2009). Some implementers believe that incentives, like bundling financial literacy training with a financial product (for instance, credit to start a small business) that help the participants to practice what is preached (fund management, book keeping, inventory management, etc.) and to visualise the impact of the training for themselves (increased revenue and profits), are more likely to be received well and to create an impact. Scientific evidence for the above is, however, lacking.

One size does not fit all

Even though there is no blueprint to a successful financial literacy programme as yet, taking a cue from the above mentioned aspects is essential to come closer to designing one. The efforts that are being put in by stakeholders to empower people while making them financially literate are commendable but need to be more focused and customised as the rule of ‘one size fits all’ doesn’t seem to apply in this sphere. Providing the right advice at the right time and with the right approach is the key and this indicates vast scope for work and innovation in this field.

Further Reading

- Spears, D (2010), ‘Economic decision-making in poverty depletes behavioral control’, CEPS Working Paper No. 213, Princeton University.

- Bertrand, Marianne, Sendhil Mullainathan and Elder Shafir (2006), “Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor”, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 8-23.

- Lusardi, A (2008), ‘Financial literacy: An essential tool for informed consumer choice?’, NBER, Working Paper 14084.

- Tufano, P, T Flacke and NW Maynard (2010), ‘Better financial decision making among low-income and minority groups’, RAND Corporation.

- Cole, S, T Sampson and B Zia (2009), ‘Valuing financial literacy training’, World Bank.

- Cole, S and GK Shastry (2009), ‘Smart money: The effect of education, cognitive ability and financial literacy on financial market participation’, Harvard Business School.

- Umapathy, D, P Agarwal and S Sadhu (2012), ‘Evaluation of financial literacy training programmes in India: A scoping study’, Centre for Microfinance, IFMR-LEAD.

05 January, 2015

05 January, 2015

By: Chandra Mani Paliwal 09 August, 2019

Really insightful with inputs of primal importance to design effective financial literacy programs.