As India’s economic growth slowed down in recent years, the reliance on monetary policy to stimulate growth increased significantly – especially during the pandemic. Analysing data from 2018-2020, Rajeswari Sengupta and Harsh Vardhan show that conventional and unconventional monetary policy actions of the RBI have had only a modest impact on the ‘term premium’ – an indicator of the market’s expectations of future interest rates. This points towards the limits of monetary policy actions alone as economic stimulus during a crisis.

Over the last few years, as India’s economic growth began slowing down, the reliance on monetary policy to stimulate growth went up significantly. This was especially the case when the country was hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) – following in the footsteps of major central banks around the world – took aggressive steps to cut policy rates1 and inject liquidity into the financial system in order to support a moribund economy. In addition to the conventional tools of monetary policy such as policy rates (repo rate and reverse repo rate) and open market operations (OMO)2, the RBI also took recourse to unconventional measures such as long-term repo operations (LTRO)3 to help infuse liquidity for a longer maturity of three years, and Operation Twist (OT) which entailed the simultaneous sale and purchase of government securities to help push down long term interest rates and flatten the yield curve.

Typically, monetary policy and the actions of a central bank are focussed on changes in the short-term interest rates while the long-term interest rates are left to be determined in the bond market. This no longer seems to hold in the case of India where the actions of the RBI are targetted towards changing both the short- and long-term interest rates.

The interest rate structure in an economy is depicted by the ‘yield curve’, which shows the yields on government bonds of various maturities. How steep the yield curve is indicative the market’s expectations of future interest rates. A simple measure of the steepness of the yield curve is the term premium. Studying its pattern reveals the outlook of the bond market on future interest rates, which is also influenced by the outlook on future inflation. In this post, we aim to assess the impact that the RBI’s unconventional policy actions may have had on the term premium during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Term premium

Term premium refers to the difference between the yields at the short end and at the long end of the yield curve and may be considered as the simplest measure of the steepness of the yield curve. In India, the long-term yield considered for term premium calculation is typically the yield on 10-year government securities (GSecs) while for the short-term yield it is typically the yield on one-year treasury bills (T-bills). The inter-bank call money rate, which is the rate at which banks lend to each other for up to 14 days, is also often considered. The long-term average figure of term premium in India – measured as the difference between the yield on 10-year GSecs and 1-year T-Bills – has been around 90 basis points (bps)4 (or 0.9%).

Term premium and conventional monetary policy action

We study the pattern of term premium in India for the two-year period between 1 January 2018 and 30 December 2020. This was a period of aggressive monetary policy actions that included a series of policy rate cuts, multiple OMOs, and unconventional measures such as the LTRO and OT.

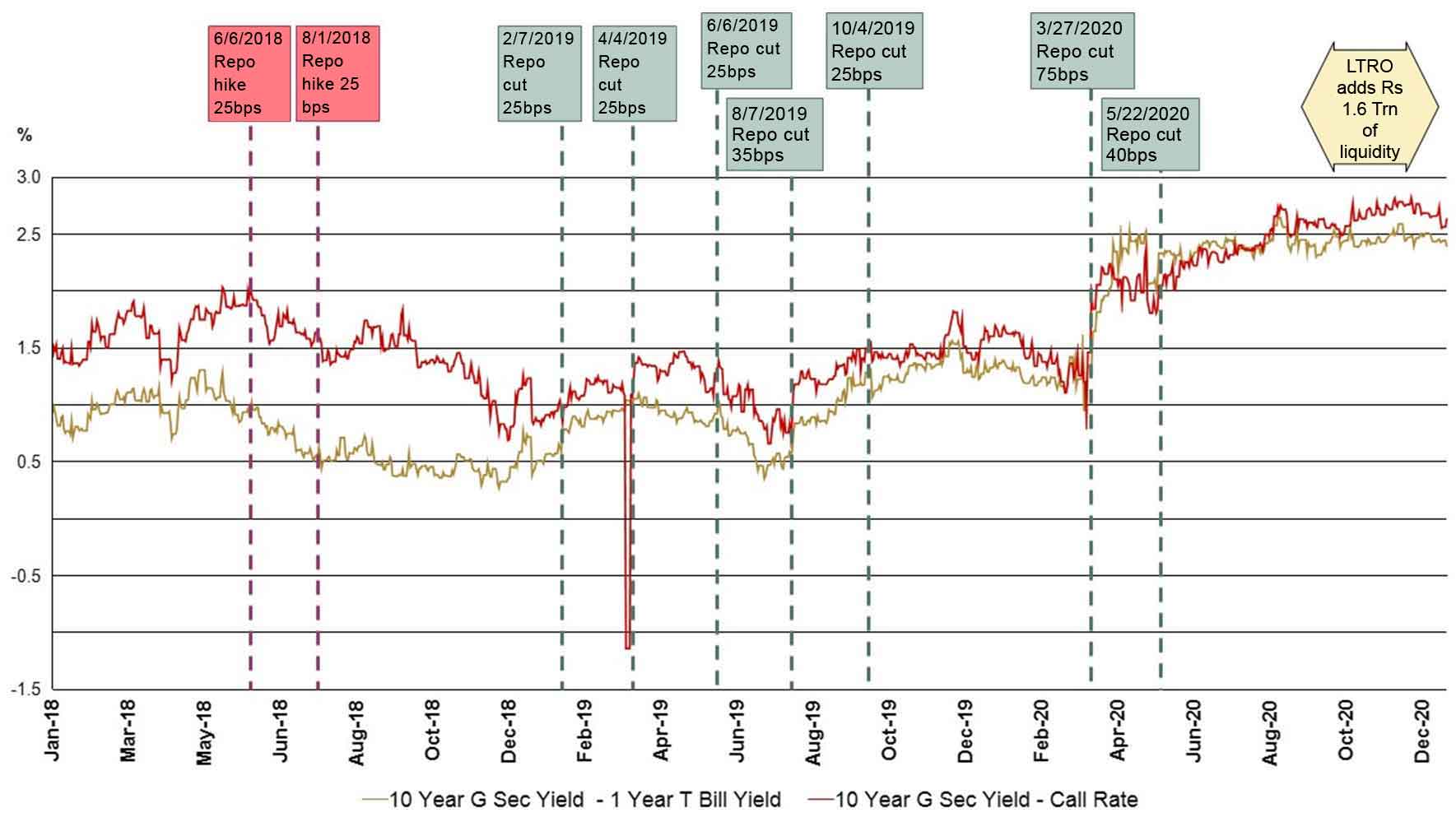

Figure 1 below shows the evolution of term premium (measured as a premium over inter-bank call rates as well as one-year T-bills yield) over the two-year period. We have highlighted the dates on which conventional repo rate-related announcements were made, and the extent of policy rate changes announced.

Figure 1. Monetary policy and term premium: January 2018 to December 2020

During this period, there were nine rate actions – the first two were repo rate hikes of 25 bps in June and August 2018, followed by seven repo rate cuts between February 2019 and December 2020, adding up to a total cut in the repo rate of 250 bps. Over this two-year period the repo rate declined by 200 bps. During this period, the yield on one-year T-bills came down from 6.41% to 3.43% indicating a decline of almost 300 bps. The inter-bank call rate also came down sharply from 5.92% to 3.18%, that is, by 274 bps. The yield on 10-year GSecs however, declined relatively modestly by about 150 bps, from 7.34% to 5.83%. Consequently, the term premium went up from around 1.5% in January 2018 (when measured against one-year T-bills) to around 2.6% in December 2020. This level of term premium is almost thrice the historical average of about 90 bps.

What is interesting to note from the chart is that the term premium declined after the first rate hike in June 2018 and with a slight lag after the second rate hike in August 2018. This suggests that the debt market believed that the rate action by the Central Bank would help control inflation, which in turn would lower the chances of future interest rate hikes. The first three rate cuts from February 2019 to June 2019 do not seem to have influenced the term premium perceptibly. It remained bound in the range between 100 and 150 bps during this period. The subsequent four rate cuts between August 2019 and May 2020 saw the term premium increase. As can be seen in Figure 1, the increase in term premium was especially sharp after March 2020, following the Covid-19-related lockdown and the resultant disruption to the economy. Following the last rate cut in May 2020, the term premium reached around 250 bps and remained at about the same level until the end of our sample period, that is, December 2020.

Term premium and unconventional monetary action

We now consider the unconventional measures adopted by the RBI to influence long-term interest rates.

The RBI conducted LTRO primarily in the months of September 2020 and November 2020 (see Figure 1 above).Total liquidity injected through this operation amounted to around Rs. 160,000 crore. However, this operation did not seem to have any perceptible impact on the term premium, which remained fairly stable at around 250 bps after the LTRO.

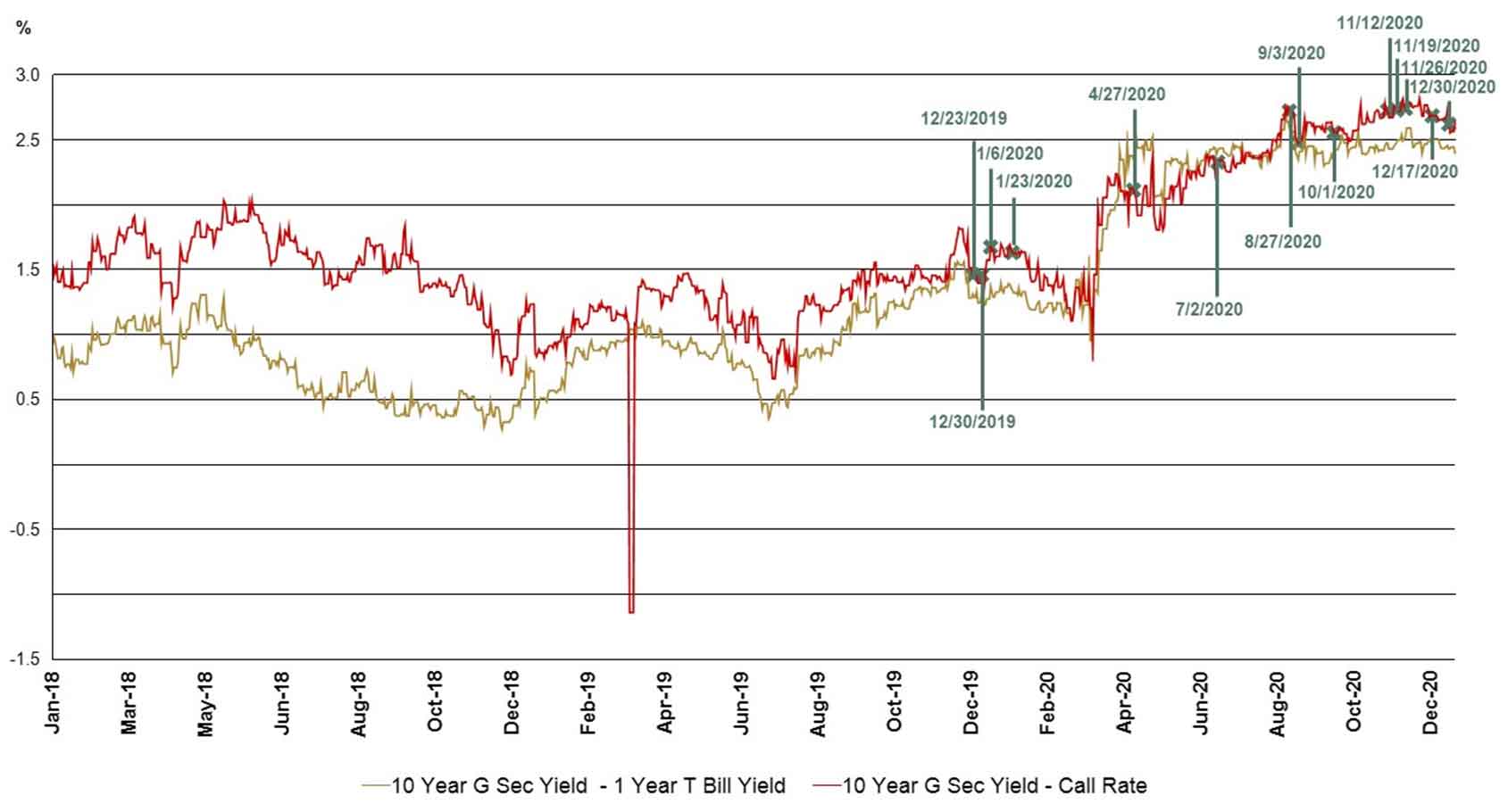

Figure 2 below shows the dates on which OT was conducted. During the period January 2018 to December 2020, there were 15 such operations each of which entailed a simultaneous purchase and sale of bonds of Rs. 10,000 crore.

Figure 2. Operation Twist and term premium: January 2018 to December 2020

As seen in Figure 2, the first OT was conducted in December 2019. Eleven of the 15 OTs in this period were conducted post March 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic began unfolding. Since the explicit purpose of OT was to bring down the term premium, we look at the average term premium for five days before and after each of the OTs and compute the difference between the two. A successful OT should result in a decrease in the term premium across the OT date. Table 1 summarises the changes in average term premium across OT dates.

Table 1. Change in average term premium across OT dates

|

Dates of Operation Twist |

Change in average term premium five days before and after Twist (in %) |

|

|

|

Term premium on call decrease / (increase) |

Term premium on one Year T-bill decrease / (increase) |

|

23-Dec-19 |

0.16 |

0.06 |

|

30-Dec-19 |

(0.08) |

(0.00) |

|

06-Jan-20 |

(0.09) |

(0.06) |

|

23-Jan-20 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

|

27-Apr-20 |

0.10 |

(0.05) |

|

02-Jul-20 |

(0.01) |

(0.01) |

|

27-Aug-20 |

0.04 |

0.09 |

|

03-Sep-20 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

|

01-Oct-20 |

0.05 |

(0.09) |

|

12-Nov-20 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

|

19-Nov-20 |

(0.05) |

(0.06) |

|

26-Nov-20 |

(0.02) |

(0.07) |

|

17-Dec-20 |

0.05 |

(0.02) |

|

30-Dec-20 |

0.10 |

0.01 |

|

Average |

0.03 |

(0.01) |

The data clearly show that, on average, OT did not have a meaningful impact on term premium. When measured over call rate, the average decline in term premium before and after OT was just 3 bps. On the other hand, when measured over the yield of 1-year T-bills the term premium increased by 1 bps across the OT.

This shows that the unconventional monetary policy actions taken by the RBI did not have any discernible impact on the behaviour of the term premium especially during the pandemic period. This implies that concerns of large fiscal deficits, high inflationary expectations, and the resulting likelihood of high future interest rates could possibly have been the more important drivers of term premium and have maintained it at a high level despite steps taken by the RBI to lower the term premium.

It could well be argued that in the absence of these actions the term premium could have become even higher. It is important to note that in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the RBI followed a strong accommodative policy for an extended period of time even when consumer price index inflation had started rising. Term premium in 2010 had shot up to around 400 bps. We could have witnessed a spike of similar or greater magnitude in term premium now considering that the macroeconomic conditions, especially growth outlook, in India are much worse now than those following the GFC. We do not have a good counterfactual and hence cannot judge the true effectiveness of the unconventional monetary policy actions of the RBI but our preliminary data analysis shows that despite a series of actions taken by the RBI the term premium has not come down substantially.

Conclusion

The pattern of term premium movement over the last two years suggests that monetary policy actions, both conventional and unconventional, have only had a modest impact. At best, these actions may have kept the term premium from rising to very high levels, similar to those witnessed following the GFC. It is possible that concerns of widening fiscal deficit, increased government borrowing and its consequences, as well as uncertainty in the inflation outlook weigh on the bond markets. This pattern of the term premium arguably points towards the limits of monetary policy actions alone as economic stimulus during a crisis period.

We thank Josh Felman and Samiran Chakraborty for helpful feedback.

Notes:

- The policy rate is the key lending rate of the central bank in a country. In India, the fixed repo rate is considered the policy rate. Repo rate is the fixed rate at which RBI lends to banks. Reverse repo rate is the rate at which the RBI borrows from commercial banks within the country. If the RBI wants to make it more expensive for banks to borrow money, it will increase the repo rate and if it wants to make it cheaper for banks to borrow money, it reduces the repo rate – an increase in the repo rate will lead to liquidity tightening and vice-versa, other things remaining constant.

- RBI conducts monetary policy through open market operations (OMO) – purchase (or sale) of securities to infuse (or absorb) liquidity. OMO though essentially a monetary tool, has to factor in the large market borrowing at times to maintain orderly financial conditions.

- Under LTRO, the RBI provides longer term loans (1-3 years) to banks at the prevailing policy rate. Hence, banks get long-term funds at lower rates, resulting in their cost of funds falling, and banks in turn reduce interest rates for borrowers.

- In finance, basis points refers to a common unit of measure.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

03 March, 2021

03 March, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.