Conventional wisdom suggests that labour-intensive, small industries are critical for generating employment. However, this column argues that policies favouring one type of industry over another - labour-intensive over capital-intensive, or SMEs over large enterprises - will not create the jobs the country needs. Rather, the key is to encourage new firms to enter manufacturing and to provide an enabling environment for businesses to expand.

There is near unanimity about the importance of the manufacturing sector in creating jobs for India’s rapidly increasing workforce. But, what is not so clear is where these jobs in manufacturing will come from. In a labour-abundant economy such as India, one would typically expect labour-intensive industries to flourish and drive employment growth. However, this has not been the case. Data from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) – the most comprehensive annual database on the organised manufacturing sector – indicates that it is the capital- and skill-intensive industries which have grown fast in the previous decade (2000-2011), while the growth of labour-intensive industries has been relatively sluggish. This, combined with the declining labour intensity of production and increasing automation of production processes in both labour-intensive and capital-intensive industries, has raised doubts about the ability of the manufacturing sector to create jobs.

Obsession with labour-intensive, small industries for job creation may be misplaced

While the growth of capital-intensive industries has been largely attributed to India’s labour laws which are widely perceived as being highly inflexible and stringent, it is worth noting that labour laws have not become any more rigid over the previous decade, and the increase in capital intensity over the time cannot be attributed to this factor alone. With unstoppable changes in technologies, an increase in capital intensity of production over time is inevitable and we can certainly not resist the adoption of new technology only to preserve jobs. Therefore, the conventional wisdom to focus on labour-intensive industries to create more jobs needs to be re-examined. If we look at employment figures over the last decade, we find that the two industries which witnessed the fastest growth of jobs were apparel, and motor-vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers. Of these, the latter is conventionally classified as capital intensive; suggesting that the obsession with labour-intensive industries for employment creation may be misplaced. Instead, it is important to envision how technological progress will change processes of production, reshape the nature of jobs, and how investments in education can provide a supply of workers with skills complementing technological innovation.

Another critical aspect of the debate on job creation in the manufacturing sector is about the role of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) vis-à-vis large enterprises in generating employment. Historically, India has supported SMEs as it believed that these enterprises would use labour-intensive methods of production, thereby generating faster employment. The Small Scale Reservation Policy (1967), which reserved production of some goods for small-scale units1, was the cornerstone of India’s manufacturing policy for about 60 years. Between 1997 and 2007, 600 out of more than a 1,000 items were de-reserved as it was argued that small firms making reserved products resisted growing or upgrading their technology as they would have to stop making those products if their investments grew beyond the permissible limits for small-scale industry.

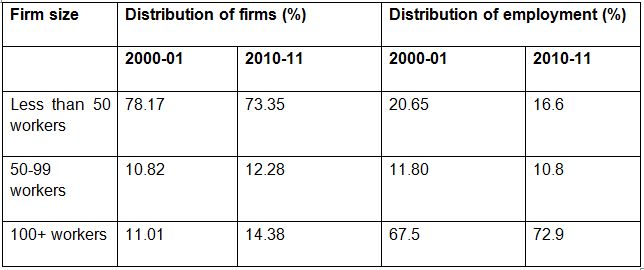

Despite significant de-reservation, there has been no major change in the size distribution of firms over the last decade, with small firms occupying a disproportionately large share of total firms2. This is reflected in the distribution of firms (Table 1). Analysing ASI data for 2000-2011, I find that approximately 75% of the total firms in the organised manufacturing sector hired less than 50 workers (small firms) (Kapoor, Forthcoming). In contrast, the share of large firms (those hiring more than 100 workers) did not exceed 15% through the decade. From an employment generation perspective too, we find that the share of small enterprises in total manufacturing employment has been significantly smaller than that of large enterprises in the last decade. What is more, the share of small enterprises in total employment has fallen over this period, while that of large firms has risen. We also find that the growth rate of employment in the small firms is significantly less than that in larger firms. Importantly, net changes in employment and growth rates tend to hide a considerable amount of job creation and destruction. Although conventional wisdom on firm dynamics says that most job creation comes from small enterprises, recent literature has shown that job destruction is equally important in their case and this perhaps explains why these enterprises hardly grow over time (Li and Rama 2012). Thus, the general claim that SMEs are the main creators of jobs in net terms is questionable.

Table 1. Distribution of firms

Age trumps size

It has been argued in the recent literature (Haltwinger et al. 2010) that what is more important than size of the firm is the age of the firm; younger firms exhibit higher rates of net job creation. For US data, the authors find that smaller firms are associated with higher employment growth primarily because of their youth, and once they control for age in their analysis, the higher employment growth of smaller enterprises disappears. Martin et al. (2014) find that in the case of India too, young establishments grow more quickly than old establishments, large establishments grow more quickly than small establishments, and employment growth has been highest for younger, larger enterprises. They also document that larger, younger establishments have higher labour productivity than smaller, older establishments. This suggests that policies targeting smaller enterprises are unlikely to lead to greater employment growth, but that encouraging new entrants could accelerate job creation.

It is indeed a welcome step that policymakers have finally recognised the importance of the manufacturing sector for job creation. However, policy recommendations based on favouring one type of industry over another - labour-intensive industries over capital-intensive industries, or SMEs over large enterprises - will not create the jobs the country needs. What is more important is to provide an enabling environment for businesses through improved infrastructure, skill development, easy access to finance and reduction in the cost of doing business, particularly the barriers to entrepreneurship. Such measures will not only encourage the entry of young, new firms but will also allow all enterprises, irrespective of size, to flourish and generate the jobs India needs.

A version of this column has appeared on Live Mint.

Notes:

- These were originally defined as firms with up to Rs 500,000 in fixed assets and fewer than 50 employees.

- The large proportion of small firms, despite de-reservation, raises important questions about why firms in India have chosen not to grow. Possible causes include tax and regulatory notches, labour regulations, and credit constraints.

Further Reading

- Haltiwanger, J, RS Jarmin and J Miranda (2010), ‘Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young’, US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, Paper No. CES-WP- 10-17.

- Kapoor, R (2015), ‘Firm Life Cycle Dynamics-Evidence from India’s Organised Manufacturing Sector’, Mimeo.

- Li, Y and M Rama (2012), ‘Firm Dynamics, Productivity Growth and Job Creation in Developing Countries: The Role of Micro and Small Enterprises’, World Development Report 2013 Background Paper, World Bank, Washington DC.

- Martin, LA, S Nataraj and A Harrison (2014), ‘In with the Big, Out with the Small: Removing Small-Scale Reservations in India’, NBER Working Papers 19942, National Bureau of Economic Research.

23 January, 2015

23 January, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.