Demonetisation and the introduction of goods and services tax were expected to accelerate the shift to formality in the economy. In this article, Renu Kohli contends that while currency in circulation has returned to previous levels, three large cash-intensive parts of the informal economy have fared poorly in the post-demonetisation and GST period. She explores whether formalisation has really occurred, or if there has been an unintended consequence of increased informality instead.

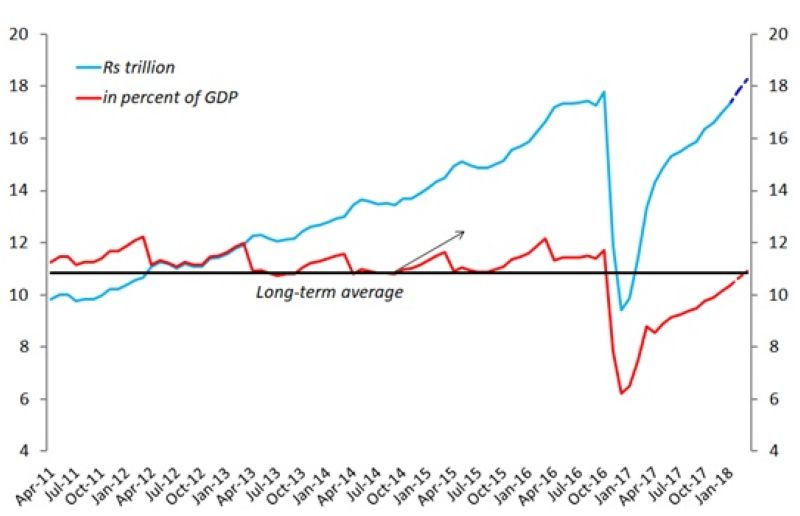

Several reports have noted that currency in circulation (CIC) reached close to pre-demonetisation levels at 99.2% on 23 February 2018. Given the year-end seasonal rise in currency demand, it will overshoot the Rs. 17.977 trillion in circulation on 4 November 2016. Observed from other aspects as well, that is, normalised to GDP (gross domestic product) and relative to its long-term average, Figure 1 below illustrates that CIC-GDP ratio has reverted to mean (average) trend and is projected to cross the threshold in March, repeating its past pattern.

Figure 1. Currency in circulation in India, April 2011-January 2018

Note: March is projection – Rs. 450 billion increase over Feb. 23 figure – using average rise in currency in circulation in the last four years.

Note: March is projection – Rs. 450 billion increase over Feb. 23 figure – using average rise in currency in circulation in the last four years. Source: RBI & author's calculations

Amongst the many questions that surface in the light of this return to cash practice, perhaps the most important and significant is about formalisation: an accelerated shift to formality was expected not only from demonetisation but the additional, similar impact of the closely-clubbed GST (goods and services tax) reform. All the more puzzling then to see as much currency circulating in the economy as before these two big changes! The mystery compounds further because of the evidence claimed in support of formalisation in the wake of demonetisation and GST. Inter alia, tax base enlargement as seen from increase in the number of taxpayers, higher tax collections from transition of more transactions to formal mechanisms as well as improved compliance from better information and scrutiny by authorities, digitisation of transactions with more use of non-cash payment and transfer modes, and so on.

If all these effects have come about because of demonetisation and GST, why has the CIC-GDP ratio not settled at a lower level? Where is cash deployed? Which segments or activities continue to be cash-dependent? Taking the commonly proffered proofs of formalisation at face value, has cash intensity in some parts of the economy increased? What is the real status of formality in the Indian economy in the post-demonetisation and GST period?

In this article, I make an attempt to find some answers to these puzzling trends and obvious questions. It is logical to start with the three sectors that were the most cash-intensive for various reasons. One, the small and tiny units operated by mostly the uneducated – dominantly agriculture, trades, and many other services – and which are the largest sources of self-employment, that is, informality in the traditional sense seen across developing countries. Two, real estate and construction segment, which has long been improperly or loosely regulated, where cash transactions have dominated giving rise to a sizeable parallel/black economy, and which serves as the major store for illicit wealth and income to evade taxation. Three, gold and jewellery segment, which is the other physical store for genuine savings, illegal wealth and incomes.

In the pre-demonetisation period, it is well known that a sizeable quantity of currency financed the three segments. But curiously, these very three segments show substantial moderation more than a year after demonetisation and seven months after the arrival of GST. Consider each by turn.

First, the rural informal sector has been quite visibly and regularly reported as strained. In the first round, the pressures were from the demonetisation-linked liquidity squeeze that hurt businesses and led to many closures and job losses, disrupted and broke down wholesale-retail supply chains, and adversely affected agriculture markets and prices. The second disturbance came from the GST, from which the formal firms are reported to have gained market share and volumes at the expense of numerous informal firms and suppliers who have either been unable to adapt to the new environment or are still in transition, while others have opted out altogether. For example, some large consumer goods’ firms have established their own direct distribution channels, bypassing previous wholesale chain structures that have either not recovered and are overall, not expected to restore to pre-demonetisation/GST levels. It is equally manifest in many farm produce markets, where traders are reported to exploit farmers’ preferences for cash payments by depressing purchase prices. The prolonged contraction in consumer durables’ even as non-durables, two-wheeler, and farm vehicle sales have revived in the past quarter, is another indicator. Such trends would suggest less transaction demand for currency than in the pre-demonetisation/GST period.

Likewise, real estate and construction has long been subdued. This is easily observed from large inventory pileups, property sales, and transaction volumes; demand for cement, steel and related construction materials; and so on. Sector estimates in the national accounts statistics match these trends. Moreover, the adverse effects of demonetisation and GST, the former drying up liquidity and the latter pushing up costs, have been magnified by new, tighter regulation (Real Estate Regulatory Agency) and the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2006 with the latter triggering fear and aversion. All of these have served to pull down the sector. There is little indication that real estate is bustling with activity, leave alone booming, that is, trends that would justify or explain similar cash operation levels as in the period before demonetisation, GST, etc. occurred. It can reasonably be assumed that cash intensity and use is lower in the latter period.

Last of all is gold and jewellery segment where too, stricter regulation and monitoring of cash purchases have pulled down sales. Again, the fear of tax authorities on the trail has also restrained volumes.

So, given that the three large cash-intensive parts of the informal economy have fared poorly in the period following demonetisation and GST, the million-dollar question is where is the previous magnitude of currency now deployed? Has formalisation really occurred as believed from indicative trends? Or have demonetisation and GST have had the unintended consequence of increasing informality instead?

The suspicion about the latter effect arises because a return of the currency-GDP ratio to previous trend levels is not matched by the preceding intensity of transactions in those parts of the economy, which were major users of cash in the pre-demonetisation and GST period. It is possible this is what has happened instead: a portion of transactions in these segments have become completely informal in the sense of a clean divide between formal and informal activities compared to the previous situation in which cash operations and exchanges flowed easily between formal and informal sectors. In other words, the formal and informal parts that were closely intertwined through a mix of cash and other payment-transfer mechanisms have completely separated after demonetisation and GST. The cleavage has occurred because of higher probabilities of detection under GST and that interlinkages between cash and non-cash operations would increase chances of scrutiny, income assessment, and taxation.

A complete parallel economy now perhaps operates off the radar and in cash; one counterpart of this may be the believed underreporting of transactions under GST system. The formal economy, which ironically would also include those operating informally on the side, executes through proper legal channels. Is this configuration the ‘new normal’? Put succinctly, has informality increased? Time will shed more light on the formalisation effects of demonetisation and GST.

This article first appeared in Financial Express: http://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/cash-signals-trend-reversion-questions-formalisation-of-the-economy-after-demo-and-gst/1088567/

06 April, 2018

06 April, 2018

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.