Burning solid fuels like firewood in homes for cooking, heating, and other energy services is the single largest source of air pollution exposure in India. In this post, Chowdhury, Chafe, Pillarisetti, Lelieveld, Guttikunda, and Dey compare the estimates of the percentage contribution of household fuel combustion to ambient air pollution, from seven independent studies. They argue that cleaning up household fuel use benefits those directly exposed, in addition to having broader population benefits by reducing ambient air pollution.

What is the single largest source of air pollution exposure in India? You would be perhaps surprised to find that the answer – with a near consensus in the published scientific literature – is neither transportation nor stubble burning. Instead, it seems to be the millions of households across the country burning solid fuels like firewood in their homes for cooking, heating, and other energy services. The resulting pollution not only has an enormous health impact on the households themselves, but it likely accounts for a quarter to half of ambient air pollution across the country. Working towards ensuring universal access to cleaner fuels like LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) should therefore be one of the pillars of India’s pollution control efforts.

When families burn solid fuels (like wood, dung, and agricultural waste) in their homes, various kinds of air pollutants are generated. One of the many pollutants emitted by this combustion of solid fuels is fine particulate matter (PM2.5, particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter1 2.5 µm). Exposure to PM2.5 has been shown to cause a range of serious health problems, including respiratory and heart disease, and can lead to early death.

Household air pollution (HAP) is the term given to emissions of PM2.5 that are generated from household solid fuel burning. People are exposed to HAP in homes where solid fuels are burned. Exposure to HAP indoors, near the source of the pollution, is estimated to result in approximately 800,000 premature deaths per year in India alone. HAP emitted indoors goes outdoors, and is a leading contributor to outdoor ambient air pollution. Other major sources of ambient air pollution in India include road transport, the industrial sector, open biomass burning, coal-fed power plants, brick kilns, construction, and road dust. Exposure to all ambient PM2.5 is estimated to result in approximately one million premature deaths annually in India.

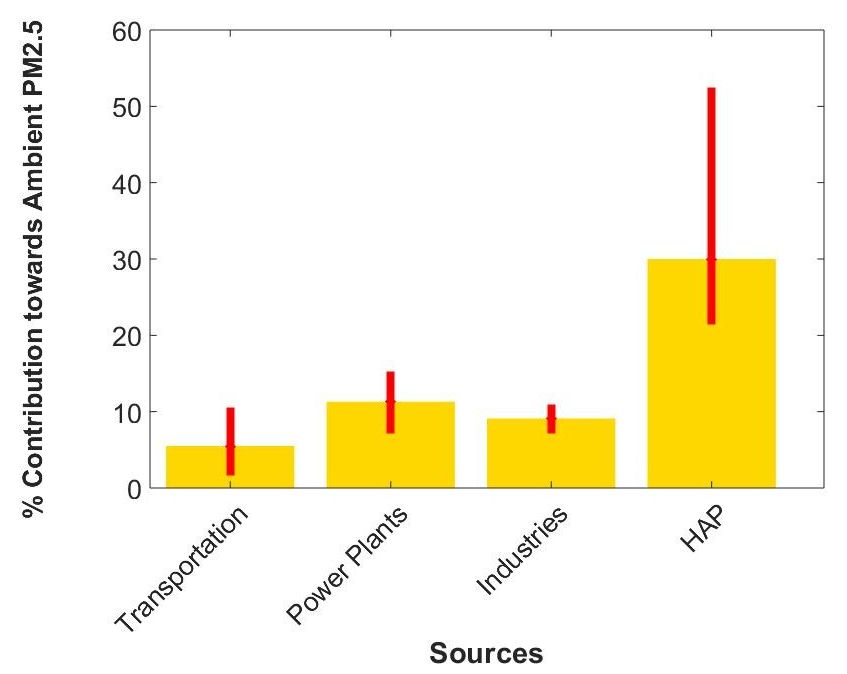

There have been seven published scientific studies2 to date that model the proportion of ambient air pollution in India and associated deaths caused by HAP. From these studies, we find that HAP causes at least 22% and as much as 52% of ambient PM2.5 in India (see Figure 1). The median estimate from these studies is about 30%. Other sources like transportation, power plants, and industries are estimated to contribute less towards ambient PM2.5 than HAP (Figure 1). Of course, within cities, especially highly polluted ones like Delhi, sources like transportation and construction dust can contribute more locally.

Figure 1. Percentage of different sources’ contribution towards ambient PM2.5 in India

Note: The height of the bars shows the median value of contribution among the published studies. The range encompasses the highest and lowest estimates among the published studies.

There is a wide range of estimates in the literature. This spread results from differences in (1) the way that air pollution models account for specific types of air pollution and chemistry (aerosol and trace gas chemistry, meteorology, and other PM2.5 formation factors); (2) the resolution of the model (geographic grid size); and (3) the years considered in the model. The definition of residential emissions also differs between studies, with emission inventories including varying combinations of cooking, heating, and lighting emissions, and some that also couple commercial emissions with residential emissions. Such differences in inputs and modeling methods are not unusual in scientific studies.

Even the lowest of the estimates of contribution of HAP to ambient air pollution indicates that household sources contribute to a significant portion of the large public health burden from ambient air pollution. Across all studies, HAP contribution to average air pollution exposure in India is estimated to be about 60% higher than all coal use, four times higher than open burning, and 11 times higher than transportation in India. Critically, this is in addition to the substantial risk households experience directly from the combustion of these fuels. Put another way, in addition to the 800,000 premature deaths annually due to indoor exposure to HAP, approximately another 300,000 can be attributed to HAP due to outdoor exposure. Cleaning up household fuel use thus, both directly benefits those exposed to HAP, and has broader population benefits by reducing ambient air pollution.

India needs to act on each of the major sources for air pollution levels to come closer to the national standards. Given that the median estimate of contribution of HAP to ambient PM2.5 is 30% and the lowest estimate is 22%, reducing emissions from household solid fuel use should be a top priority for the Indian government. The Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana3 (PMUY) is an important policy effort in this direction. However, it is essential to look at further expanding the access of LPG to more beneficiaries, and work towards ensuring sustained use of LPG by households that have already joined the programme. We should also redouble efforts – most likely, ensuring access to reliable electricity – to substitute for other household pollution sources, such as bathwater heating and kerosene lighting. Averting 1.1 million premature deaths annually requires taking bold strides towards universal access to cleaner residential fuels.

Please refer to http://www.urbanemissions.info/india-emissions-inventory/emissions-in-india-household-cooking-heating/ for interactive data and figures. (http://www.urbanemissions.info is maintained by Dr. Sarath Guttikunda.)

Notes:

- The aerodynamic diameter of a particle is defined as that of a sphere, whose density is 1 g cm −3 (cf. density of water), which settles in still air at the same velocity as the particle in question.

- The seven published studies are Chafe et al. (2014), Lelieveld et al. (2015), Butt et al. (2016), Silva et al. (2016), GBD-MAPS Working Group (2018), Conibear et al. (2018), and Chowdhury et al. (2019).

- In 2016, the government announced Ujjwala scheme, which provides financial assistance to poor households to meet the upfront cost of LPG connection.

Further Reading

- Butt, EW, A Rap, A Schmidt, CE Scott, KJ Pringle, CL Reddington, NAD Richards, MT Woodhouse, Julian Ramirez-Villegas, H Yang, V Vakkari, EA Stone, M Rupakheti, PS Praveen, PG Van Zyl, JP Beukes, M Josipovic, EJS Mitchell, SM Sallu, PM Forster, DV Spracklen (2016), “The impact of residential combustion emissions on atmospheric aerosol, human health, and climate”, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(2):873-905.

- Chafe, Zoë A, Michael Brauer, Zbigniew Klimont, Rita Van Dingenen, Sumi Mehta, Shilpa Rao, Keywan Riahi, Frank Dentener and Kirk R Smith (2014), “Household cooking with solid fuels contributes to ambient PM2.5 air pollution and the burden of disease”, Environmental Health Perspectives, 122(12):1314-1320. Available here.

- Chowdhury, Sourangsu, Sagnik Dey, Sarath Guttikunda, Ajay Pillarisetti, Kirk R Smith, and Larry Di Girolamo (2019), “Indian annual ambient air quality standard is achievable by completely mitigating emissions from household sources”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116:10711-10716.

- Conibear, Luke, Edward W Butt, Christoph Knote, Stephen R Arnold and Dominick V Spracklen (2018), “Residential energy use emissions dominate health impacts from exposure to ambient particulate matter in India”, Nature Communications, 9(1):1-9.

- GBD-MAPS Working Group (2018), ‘Burden of Disease Attributable to Major Air Pollution Sources in India’, Special Report 21, January 2018.

- Lelieveld, Jos, JS Evans, M Fnais, D Giannadaki and A Pozzer (2015), “The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale”, Nature, 525:367-371.

- Silva, Raquel A, Zachariah Adelman, Meridith M Fry and J Jason West (2016), “The impact of individual anthropogenic emissions sectors on the global burden of human mortality due to ambient air pollution”, Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(11):1776-1784.

19 August, 2019

19 August, 2019

By: Ranjit Devraj 19 April, 2021

Ambient air in Delhi has been shown to have unusually high on chlorides by recent IIT studies. These are obviously coming from the burning of plastics including in WtE plants that burn some 5,000 tonnes of unsegregated waste daily. How to solve this?