Eight years after the adoption of Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) by the RBI, Garga, Lakdawala and Sengupta evaluate the success of this framework. They use two approaches to assess the credibility of the RBI's commitment to inflation targeting in the pre-Covid period – using forecast data, they find that the markets’ perception was that the RBI's response to inflation would be greater and that market participants revised their expectations of interest rates by a larger magnitude in response to macroeconomic surprises in the post-FIT period.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) adopted a Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) framework in 2015. This was a watershed reform as until then monetary policy in India was not governed by a clear, well-defined objective. FIT gave the RBI the legal mandate of achieving price stability, while keeping an eye on growth. Price stability was defined as a 4% Consumer Price Index inflation target, with a +/- 2% band around it.

Eight years since the adoption of FIT in India, it is worth asking how this framework has performed. In a recent paper (Garga et al. 2022), we propose a novel framework to evaluate the success of this reform, specifically to gauge the credibility of the RBI’s commitment to the FIT regime.

An important channel through which inflation targeting affects macroeconomic outcomes is the anchoring of inflation expectations. Simply put, in an effective inflation targeting regime, economic shocks do not destabilise agents’ long-run inflation expectations. This is because the agents believe that the central bank would respond to these shocks, and take the necessary policy actions to keep inflation at target-level. Hence, the extent to which inflation expectations have become anchored could potentially be a metric to assess the success of inflation targeting. Another typical way to evaluate inflation targeting would be to analyse the patterns in macroeconomic outcomes since its adoption.

Both these approaches are problematic. First, expectations of agents or macroeconomic outcomes could be impacted by macro shocks as well as inflation targeting. For example, in the case of India, since the rollout of FIT in 2015, several large shocks and policy changes have hit the economy, including demonetisation in November 2016, adoption of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, and a steep fall in global oil and commodity prices. These changes make it challenging to isolate the effect of adoption of FIT from the effect of these other domestic and global forces. Second, it is difficult to assess the extent of anchoring of inflation expectations because emerging economies like India often lack data on agents’ inflation expectations at longer horizons (such as five-year or ten-year expectations).

To circumvent these problems, we propose an alternative approach where we evaluate whether central banks’ commitment to inflation targeting is believed to be credible by agents.

Using survey forecast data

We ask a simple question: with the adoption of FIT, did financial market participants believe that the RBI is serious about keeping inflation under control? In other words, did the markets perceive FIT as a credible commitment on the part of the RBI?

This is important; unless the agents believe the RBI’s commitment to inflation targeting to be credible, their inflation expectations may not get anchored, and that in turn would hamper the effectiveness of the FIT regime. Therefore, instead of analysing inflation expectations, we study how the agents’ expectations about the RBI’s actions may have changed with the adoption of FIT.

We use novel survey forecast data over the period 2010 to 2020 to help understand the shift to the FIT regime. The data includes monthly survey of professional forecasters’ expectations about one-quarter to two-year-ahead macroeconomic variables. We obtain this data from Consensus Economics, as well as Bloomberg Economic Forecasts. Both of these databases survey a panel of professional forecasters every month, and collect their forecasts for key Indian macroeconomic variables, including inflation (measured using Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Wholesale Price Index (WPI)), output (measured using GDP and the Index of Industrial Production), and nominal INR/USD exchange rates.

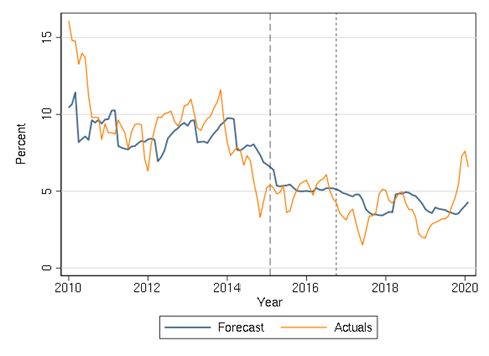

In Figure 1 we show the Consensus Economics forecasts for inflation, along with their actual (realised) values. We find that the forecasts track the trends in the actual data reasonably well.

Figure 1. Forecast and actual trends in CPI inflation

Note: The dotted vertical lines correspond to February 2015, when the Monetary Policy Framework Agreement was signed between the RBI and the Ministry of Finance thereby introducing FIT for the first time in India, and October 2016, when the newly constituted Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) held its first meeting to decide the policy repo rate as part of the FIT framework.

We find that the average inflation forecasts have gone down in the post-FIT period. We show in the paper that the average output growth forecasts have remained roughly unchanged relative to the pre-FIT period.

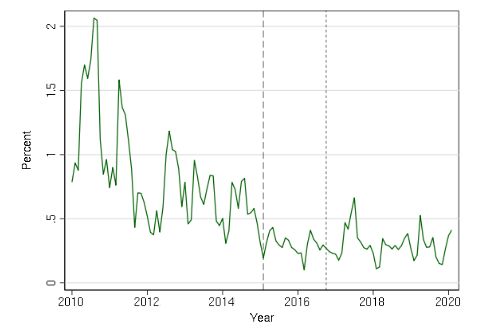

Using the forecasts of the individual survey participants, we study how disagreement across forecasters has changed since the adoption of FIT. In Figure 2, we plot the standard deviation of the fiscal year forecasts of CPI inflation across the forecasters. If the FIT mandate was credible, we would expect the forecasts from individual respondents, especially for CPI inflation, to converge – in other words, we would expect the standard deviation of the forecasts to be lower in the post-FIT period. We find that there is indeed a clear decline in the standard deviation of CPI inflation forecasts in the post-FIT period.

Figure 2. Percentage deviation in CPI inflation forecasts

Note: The dotted vertical lines correspond to the introduction of FIT in February 2015, and the first meeting of the MPC to decide the policy repo rate as part of the FIT framework in October 2016.

This preliminary analysis of data trends gives us the confidence that the forecast data are reliable and that there has been a decline in the mean, and cross-sectional variance of inflation forecasts coinciding with the adoption of FIT.

Market-perceived monetary policy

We use two different approaches to assess the market’s perception of FIT as a credible commitment. In our first approach we investigate whether the agents believe that the RBI would respond more to inflation during the FIT regime compared to the pre-FIT period.

We find that this is indeed the case. Our analysis shows that market-perceived response of the RBI to inflation doubles in the post-FIT period. Specifically, the market perceived that a 1 percentage point rise in inflation would lead to a 0.66 percentage point increase in the policy rate in the post-FIT period, compared with a 0.35 percentage point increase in the policy rate in the pre-FIT period. While forecasters expect the RBI to respond to inflation in the post-FIT sample, the same does not hold for output growth.

Another change brought about with the introduction of the FIT framework was that the inflation target came to be defined in terms of CPI inflation. In the pre-FIT period, monetary policy was primarily formulated based on WPI inflation. We, therefore, also test whether the shift to CPI inflation target was considered credible by the market.

Our results show that the market did believe that the RBI reacted to WPI inflation in the pre-FIT period but then began responding to CPI inflation in the post-FIT period. Moreover, the perceived response to CPI inflation post-FIT is larger than the perceived response to WPI inflation pre-FIT. Thus, the RBI’s switch to CPI from WPI as the preferred inflation measure seems to have been internalised by the private forecasters.

Macroeconomic news surprise

In our second approach, we use information from macroeconomic data releases. Data about macro variables such as GDP, CPI, WPI etc. are periodically released by the National Statistical Organisation (NSO). If any such data release comes across as a surprise to the forecasters, then they are likely to change their future expectations about how the RBI might react to that data release. We conjecture that the extent of this revision in expectations would depend on the market’s belief regarding the RBI’s commitment to FIT.

For example, if a data release announces that CPI inflation is higher than what the market was expecting, then forecasters may anticipate that the RBI will raise interest rates in response to the higher-than-expected inflation. If the market perceives FIT to be a credible commitment, then they will expect the RBI to respond more to news about a surprise inflation in the post-FIT period compared to the pre-FIT era.

For this approach, we use an alternative data set from Bloomberg that surveys forecasters leading right up to the dates of data releases of prominent macroeconomic indicators. We construct a ‘macroeconomic news surprise’ measure as the difference between the values of indicators announced in the news release, and the median expected values prior to the release.

We find that, in the pre-FIT period, market participants did not systematically revise their expectations of interest rates in response to news surprises. In the post-FIT sample, however, this pattern changes drastically for both CPI and GDP news releases, and interest rate expectations respond markedly more to macroeconomic surprises.

The results from our two approaches therefore arrive at a broadly consistent conclusion – in the post-FIT period, the market expects the RBI to respond more strongly to inflation.

Conclusion

We have formulated a new approach to assess the credibility of the RBI’s commitment to inflation targeting. We use a variety of survey forecasts to study how economic agents changed their beliefs about the RBI’s actions after the adoption of inflation targeting. We find that since the adoption of inflation targeting in 2015 till the start of the pandemic in 2020, markets believed that the RBI was more responsive to inflation. This is consistent with an important goal of inflation targeting: making the central bank more transparent and credible in its fight against inflation.

Further Reading

- Garga, V, A Lakdawala and R Sengupta (2022), ‘Assessing central bank commitment to inflation targeting: Evidence from financial market expectations in India’, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Working Paper 2022-017.

- Lakdawala, A and R Sengupta (2023), ‘Measuring Monetary Policy Shocks in Emerging Economies: Evidence from India’, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Working Paper 2022-021 (forthcoming in Journal of Money, Credit and Banking).

- Mathur, A and R Sengupta (2019), ‘Analysing monetary policy statements of the Reserve Bank of India’, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Working Paper 2019-012.

24 May, 2023

24 May, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.