It is widely known that income shocks may trigger spurts of violence. This column explores whether workfare programmes can help mitigate support for violent movements. It finds that MNREGA has had a moderating effect on the intensity and incidence of terrorist violence in India, through the provision of more stable incomes - even for those who do not directly participate in the programme.

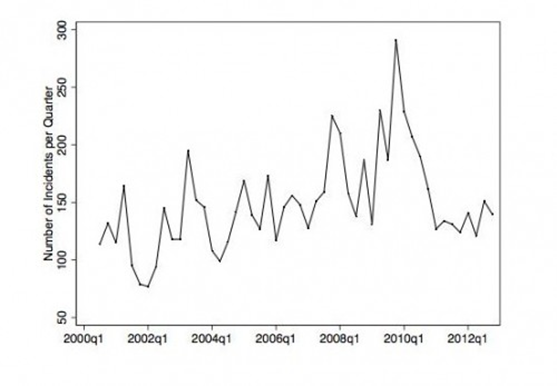

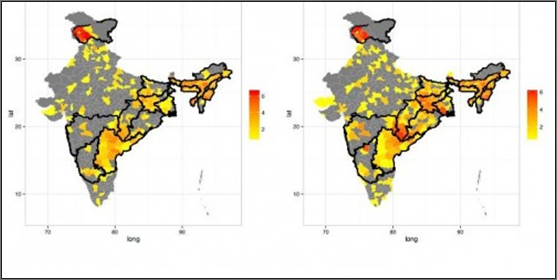

India has faced many internal security challenges since independence. In recent years, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has described Naxalism as the greatest threat to internal security. But this is not the only conflict that perturbs India’s development. Regular spurts of violence occur in northeast, south and central India, where various movements strive for more political representation, independence or equality. This pattern does not seem to have changed much in recent years - if anything, there appears to have been an intensification of terrorist violence (see Figure 1). This intensification is also associated with a spatial expansion - more districts have experienced terrorist violence since 2006 than earlier (Figure 2)1 . While individual motives may vary, it is well established in the scholarly literature that income shocks may trigger spurts of violence as it is easier for violent movements to gain support in an environment of need and hardship (see, for example, Vanden Eynde 2011 or Kapur 2013 for recent contributions).

Figure 1. Number of terrorist incidents in India, 2000-2012

Figure 2. Spatial dimension of terrorist attacks in India, before 2006 (left) and after 2006 (right)

Income shocks and violence

So how can the Indian State address this relationship between income shocks and violence? Despite structural change, more than 47% of the total employment in India is in the agricultural sector (World Bank 2014), and the agricultural sector is very dependent on monsoon rainfall2. Hence, a potential way of mitigating income shocks in the agricultural sector is to make it more resilient against adverse weather shocks. This has been a long standing goal of development policy in the country, fostering the construction of dams and irrigation canals, and promotion of more robust crop varieties. However, there is a limit to the extent to which new physical infrastructure can moderate the negative effects of a lack of rainfall. These are shocks that will need to be cushioned through social security schemes. Such a scheme was introduced through the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) 20053.

In my research, I analyse the evolution of the relationship between monsoon rainfall, agricultural production, wages and terrorist violence (Fetzer 2013). The key question is whether the effect of monsoon rainfall on agricultural production, wages and terrorist violence changed with the introduction of MNREGA.

MNREGA has broken the link between monsoon rainfall and conflict

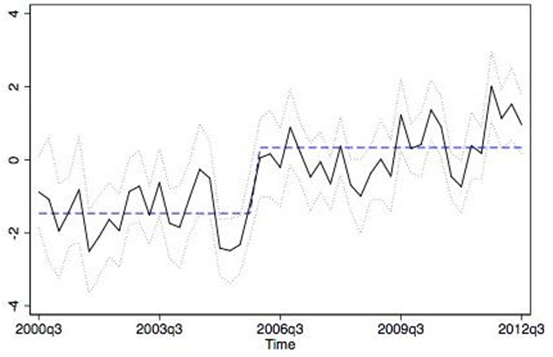

My research documents three key findings. Firstly, there exists a strong relationship between agricultural Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and monsoon rainfall - a 1% increase in monsoon rainfall increases agricultural GDP by 0.45%. It is through this channel that conflict levels are dependent on monsoon rainfall across India. Figure 3 shows the relationship between monsoon rains and conflict over time for districts where MNREGA was implemented in the first phase of the programme (starting early 2006). Before MNREGA, a clear negative association between monsoon rainfall and conflict is seen. The better the monsoon rainfall, the less is the likelihood and intensity of conflict in a district. However, following the introduction of MNREGA (2006 onwards), this relationship disappears.

Figure 3. Effect of monsoons on terrorist violence in MNREGA Phase I districts, 2000-2012

My first finding suggests that MNREGA is a potential antidote to the seasonal nature of terrorist violence4. But the research should not stop at this headline finding as it is important to explore the mechanisms through which this moderating of violence occurs. Does the demand for employment under MNREGA follow the seasonal pattern and is it associated with a lack of rainfall? That is to say, does a lack of rainfall increase take-up, indicating that the scheme effectively works as an insurance against a poor monsoon? Further, does MNREGA moderate agricultural wages in general? If this is the case, then the benefits from MNREGA would spill out to people who do not directly participate and work under MNREGA but are still are able to benefit from more stable wages. My research offers the following answers to these questions.

MNREGA works as insurance

My second key finding is that MNREGA take-up increases dramatically if monsoon rainfall turns out to be poor. A 1% increase in monsoon rainfall reduces participation in the scheme by 0.458%. Hence, people demand MNREGA employment more when agricultural output and GDP are low, on account of a poor monsoon.

Cushioning agricultural wages

The third major observation of my research is that MNREGA moderates the responsiveness of agricultural wages with respect to monsoon rainfall. Before MNREGA was introduced, a bad monsoon resulted in low agricultural wages, especially during the harvest season. However, this relationship disappeared once the employment scheme was introduced. By providing a stable work option outside of agriculture, MNREGA helps improve the general bargaining power of agricultural labourers. Hence, wages are more stable even for those who do not participate in the programme. This implies that landlords hiring agricultural labourers also bear the financial burden of providing insurance, not just the State.

Conclusion

My research highlights that there are important indirect benefits from MNREGA in the form of moderating effects on the intensity and incidence of terrorist violence, through the provision of more stable incomes. These findings have important implications when evaluating the fiscal costs of MNREGA for India. Clearly, the scheme has developed into a major fiscal burden as each year the cost of hundreds of millions of person days of work are being borne by the State and the Indian tax payer. However, the key result presented here suggests that MNREGA has important implications for the dynamics of intra-state conflict. By moderating violence, MNREGA may give rise to a peace dividend. Furthermore, the results suggest that the benefits of the programme extend beyond participants to include those who do not directly enroll in the employment scheme. Through its stabilising effect on agricultural wages, MNREGA allows individuals who do not themselves participate to benefit from higher and more stable wages.

This column has been reprinted with permission from India at LSE.

Notes:

- The dataset used here was derived from around 30,000 newspaper clippings relating to terrorist and insurgency violence in India, collected by the South Asian Terrorism Panel (SATP). The clippings have been transformed into an analysable dataset on conflict in India using methods described in Fetzer (2013). The data has been extensively used for research on Naxalite violence in India.

- A recent report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch estimates that below normal monsoon could bring down India’s GDP growth by 0.5-0.75%; see Economic Times, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/poor-rains-may-wash-out-50-75-bps-from-gdp-growth-bank-of-america-merrill-lynch/articleshow/34210612.cms.

- MNREGA provides a legal guarantee for at least 100 days of employment in every financial year to adult members of any rural household willing to do unskilled manual work at the notified wage.

- This means that following a bad agricultural season, owing to bad monsoons, conflict increases; following a good agricultural season sowing to good monsoons, conflict decreases.

Further Reading

- Fetzer, T. (2013), ‘Can Workfare Programs Moderate Violence? Evidence from India’, Mimeo, 1–42.

- Fetzer, T. R. (2013), ‘Developing a Micro-Level Conflict Data Set for South Asia’, 1–17.

- Kapur, D., Gawande, K., & Satyanath, S. (2012), ‘Renewable Resource Shocks and Conflict in India’s Maoist Belt’, Mimeo.

- Vanden Eynde, O. (2011), ‘Targets of Violence: Evidence from India’s Naxalite Conflict’, Mimeo, (November), 1–50.

05 May, 2014

05 May, 2014

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.