The proliferation of cash transfer programmes in developing countries has raised concern regarding a crowding-out effect on citizens' demands for investment in universal public services. Based on a household survey in rural Pakistan, this article shows that this is not necessarily true. It notes important sub-national differences in programme effects, with greater positive spillovers in settings where public services are functional and valued by citizens.

Cash transfer programmes have been one of the most widely adopted social policies implemented by a variety of governments in developing countries, as a form of social protection and poverty alleviation (Fiszbein et al. 2009). Numerous independent evaluations, from programmes around the world, have demonstrated that giving money directly to poor citizens does not create State dependency and can have positive impacts in supporting poor households to make investments in human development, particularly health and education (Gertler 2000, Mourão and de Jesus 2012, Skoufias and McClaerty 2001, Banerjee et al. 2017, Evans and Popova 2017, Hanna and Olken 2018) However, the proliferation of cash transfer programmes, in developing countries with uneven delivery of public services – such as health and education, and physical infrastructure – has generated an important policy debate about whether these programmes may crowd-out citizens' demands for investment in universal public services in resource-constrained environments.

We examine whether the successful implementation of an unconditional cash transfer (UCT) programme has influenced demands for welfare amongst poor citizens in rural Pakistan. In 2008, the Government of Pakistan established the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP). The UCT provides direct cash transfers to over five million women and their families throughout the country. The programme uses a proxy means test1 to select beneficiaries, based on a landmark poverty survey conducted in 20102. Over the span of a decade, BISP has become Pakistan’s largest social safety net, targetted exclusively at low-income women. Independent evaluations of BISP have found positive effects of the cash transfer programme on household poverty, consumption levels, labour supply, and some measures of gender empowerment (Oxford Policy Management, 2016, Ambler and Debraw 2017, 2019). These effects have been usually small in size, which should not come as a surprise given the small size of the transfer itself (US$30).

Data and methodology

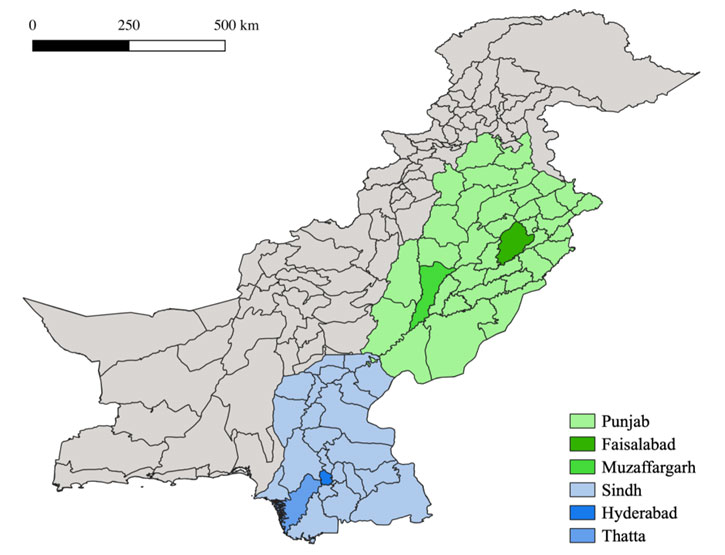

We use data from an original household survey conducted in 2019, covering 2,254 households across four districts of Pakistan’s two most populous provinces – Punjab and Sindh (see map below) (Jamil and Iudice 2020). We sample respondents close to the programme eligibility threshold3 to make inferences by comparing programme recipients and non-recipients. The four districts have diverse characteristics, allowing us to analyse whether the federally administered safety net has different sub-national effects on demands for welfare in settings where the quality of public services vary significantly.

Figure 1. Map of Pakistan

Our study contributes to a small but growing body of evidence that examines how citizens may change their demand for welfare in response to the successful implementation of social welfare programmes (Khemani et al. 2019). Much of the literature on citizen preferences for redistribution focus on industrialised countries, leaving us with a limited understanding of citizen preferences in lower income settings (Meltzer and Richard 1983, Alesina et al. 2011, Alesina et al. 2018). Our results are preliminary, but suggestive of important trends in citizen attitudes toward welfare, in a setting where a large-scale cash transfer programme has been successfully implemented, but critical investments in public health, education, and physical infrastructure remain highly uneven.

Cash transfers versus other forms of welfare provision

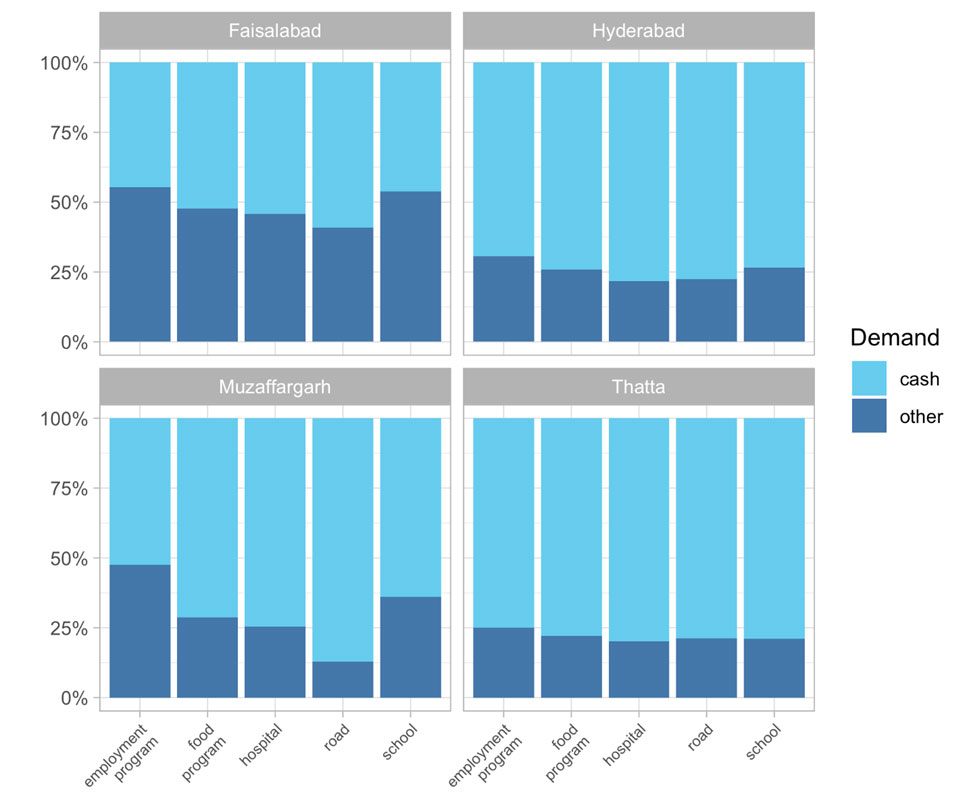

First, in order to capture the demand for different types of welfare, we presented respondents with a hypothetical trade-off. We asked all survey respondents: “[...] if the government would have additional funds to allocate in your town (or village), would you rather receive a cash transfer or: (i) a new public school, (ii) a new public hospital, (iii) a new public road, (iv) a public works employment program, or (v) an in-kind transfer”. We phrased our question in a similar manner to Khemani et al. (2019). Interestingly, while the respondents of the survey they conducted in the state of Bihar in India were more likely to choose traditional welfare provision (roads, public health, and nutrition services for children) over a cash transfer, respondents in our sample overwhelmingly chose cash transfers against all other options presented. The only outlier in our sample is the relatively more affluent district of Faisalabad, where there is much more variation in the survey responses. Faisalabad is different from the other districts in our survey because basic public services in the district, such as provision of public schools and government health clinics, is high relative to the other three districts sampled.

Figure 1. Demand for cash transfers versus others forms of welfare

Unfortunately, we do not have baseline data on citizen welfare preferences before the BISP cash transfer was introduced in 2008. However, our empirical strategy allows us to test whether the demand for various types of welfare differs across recipients and non-recipients of cash transfers. We do not find any significant difference among the two groups in our sample of respondents around the eligibility threshold. In the district of Faisalabad, we find interesting heterogeneous effects along the gender dimension: women recipients of BISP are more likely to choose an additional cash transfer programme, while male respondents living with female beneficiaries are more likely to choose a public employment programme over cash. The results suggest potentially important gendered differences in the way women and men value specific types of welfare policies. Women in our sample appreciated the flexibility of using cash for household needs, while their male household members gave greater importance to public employment schemes, as the primary driver of poverty alleviation.

Citizens’ preferences for redistribution

Second, our household survey measured citizens’ preference for redistribution, using a standard formulation borrowed from the World Values Survey, widely used in the literature (one example, among many, being Alesina et al. 2011). The respondents are asked whether, in their view: (i) The government should improve the standard of living of all poor Pakistanis, which signals higher preference for redistribution; or (ii) each person should take care of themselves, which indicates lower preference for redistribution. As is to be expected, in high-poverty settings, we find that the support for redistribution is very high across all respondents sampled. Seventy-five per cent of respondents were in favour of higher redistribution. However, we find that BISP cash recipients are approximately 30% less likely to support higher redistribution in comparison to non-beneficiaries. These findings challenge the idea that welfare recipients will demand greater redistributive policies.

In our data we can safely exclude a wealth effect, measured in terms of asset accumulation, to explain why cash transfer recipients may lower their preferences for redistribution. There is of course an income effect, which increases the short-term spending power of the recipients of cash transfer. However, this modest amount of the quarterly cash transfer is used by BISP programme recipients to overcome the most pressing needs of their households, typically spending on food, and other household expenses.

Unpacking the sub-national effects of cash transfers

We find that large federally administered programmes like BISP have uneven impacts on citizen demands for welfare, based on the settings that the recipients live in. Further evidence that the quality of local institutions surrounding recipients are key in assessing programme effects, is apparent through a more fine-grained sub-national analysis, by district. For example, when asked how the transfer is used, all recipients in Thatta, the poorest district in our sample, spend it on food, as compared to 82% of recipients in the relatively affluent district of Faisalabad. About 40% of respondents in Faisalabad use a part of the transfer for spending on children’s school fees, versus just 15% in Thatta. Another example is access to short-term credit. Households in which at least one woman is a recipient of BISP are more likely to have a running line of credit at the local grocery shop – but only in Faisalabad. These results suggest that in settings where public services are reasonably more effective, beneficiaries see greater value in them.

Conclusion

Our research highlights the immense popularity of cash transfer programmes amongst citizens in a variety of low-income settings in Pakistan. However, this support for cash transfers, is not necessarily evidence of a crowding-out of demands for other essential public services. In fact, the evidence that is emerging from our survey is one of sub-national differences in programme effects, on citizen demands for targetted and more universal forms of welfare. A standardised poverty score does not capture the important sub-national differences between districts that shape how citizens experience poverty and value the quality of available public services. In some settings, critical investments in improved public service delivery might benefit certain areas much more than additional targetted cash programs. From a political economy perspective, it may not be easy to convince politicians to commit to these investments, given that improving the quality of local public services is often far more complex than distributing money to citizens. However, our findings suggest that there are greater positive spillovers of cash transfer programmes in settings where public services are both functional and valued by citizens.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Notes:

- A proxy means test (PMT) uses a series of proxies for household income and welfare to determine whether an individual or family is eligible for a government programme.

- In 2010, Pakistan’s first poverty census was conducted by BISP with technical support from the World Bank. Each household survey was given a poverty score. This was the first initiative to create a universe of potential welfare beneficiaries at the national level. The data collected in the 2010 poverty census, became the basis for the country’s National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER).

- We use a regression discontinuity design here. Regression discontinuity design is an econometric technique used to estimate the effect of an intervention when the potential beneficiaries can be ordered along a cut-off point. The beneficiaries just above the cut-off point are very similar to those just below the cut-off. The outcomes are then compared for units just above and below the cut-off to estimate the causal effect of the intervention.

Further Reading

- Alesina, A, P Giuliano, A Bisin and J Benhabib (2011), ‘Preferences for redistribution’, in J Benhabib, A Bisin and M Jackson (eds.), Handbook of Social Economics.

- Alesina, Alberto, Stefanie Stantcheva and Edoardo Teso (2018), "Intergenerational Mobility and Preferences for Redistribution", American Economic Review, 108(2): 521-54.

- Ambler, K and A de Brauw (2017), ‘The impacts of cash transfers on women’s empowerment: Learning from Pakistan’s BISP program’, World Bank Discussion Paper No. 1702.

- Ambler, K and A De Brauw (2019), ‘Household labor supply and social protection: Evidence from Pakistan’s BISP cash transfer program’, IFPRI Discussion Paper.

- Banerjee, Abhijit V, Rema Hanna, Gabriel E Kreindler and Benjamin A Olken (2017), “Debunking the Stereotype of the Lazy Welfare Recipient: Evidence from Cash Transfer Programs”, The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2): 155-184.

- Cheema, I, S Hunt, S Javeed, T Lone and S O’Leary, ‘Benazir Income Support Programme Final Impact Evaluation Report’, Oxford Policy Management.

- Fiszbein, A, N Schady, FHG Ferreira, M Grosh, N Keleher, P Olinto and E Skoufias (2009), ‘Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty’, Technical Report 47603, The World Bank.

- Gertler, P (2000), ‘The Impact of PROGRESA on Health’, IFPRI Discussion Paper.

- Jamil, R and M Iudice, ‘Being Seen By the State: Cash Transfers and Women’s Political Participation in Pakistan’, Working paper.

- Hanna, Rema and Benjamin A Olken (2018), “Universal Basic Incomes versus Targeted Transfers: Anti-Poverty Programs in Developing Countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(4): 201-226.

- Khemani, S (2019), ‘Outsized focus on cash transfers is missing the point’, Brookings, 19 April.

- Khemani, S, J Habyarimana and I Nooruddin (2019), ‘What do poor people think about direct cash transfers?’, Brookings, 8 April.

- Meltzer Allan H and Scott F Richard (1981), “A rational theory of the size of government”, Journal of Political Economy, 89: 914-27

- Mourão, Luciana and Anderson Macedo de Jesus (2012), “Bolsa Famlia (Family Grant) Programme: Analysis of Brazilian income transfer programme”, The journal of field actions: Field Actions Science Reports, 3.

- Skoufias, E and B Mcclafferty (2003), ‘Is PROGRESA working? Summary of the results of an evaluation by IFPRI’, IFPRI Discussion Paper.

24 June, 2021

24 June, 2021

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.