While digital technologies can potentially make firms more efficient, they require complementary skills and reliable infrastructure – conditions that vary across sectors and regions. This article examines how India’s 2016 demonetisation – a sudden, nationwide withdrawal of cash that accelerated digital payments – affected firms in the service and manufacturing sectors differently. It finds that inequality deepened across sectors due to the limited mobility of workers.

Digitalisation is widely viewed as a new engine of economic growth (Agarwal et al. 2019, Colecchia and Schreyer 2002), especially for developing economies. From e-commerce to digital payments, new technologies promise to boost productivity, formalise transactions, and create better jobs. Governments have embraced this vision: India’s Digital India campaign, for instance, aimed to empower citizens and modernise business. However, in developing countries, the implications of digitalisation remain unclear due to various frictions in credit and labour markets. A key question therefore remains underexplored: does digitalisation benefit all sectors equally, or can it create new divides within the economy?

This question is especially relevant for countries like India, where services have grown rapidly but manufacturing has lagged. While digital technologies have the potential to make firms more efficient, they also require complementary skills and reliable infrastructure – conditions that vary across sectors and regions. In a recent study (Chen 2026), I explore this tension by examining how India’s 2016 demonetisation – a sudden, nationwide withdrawal of cash that accelerated digital payments – affected firms in the service and manufacturing sectors differently.

A nationwide policy shock

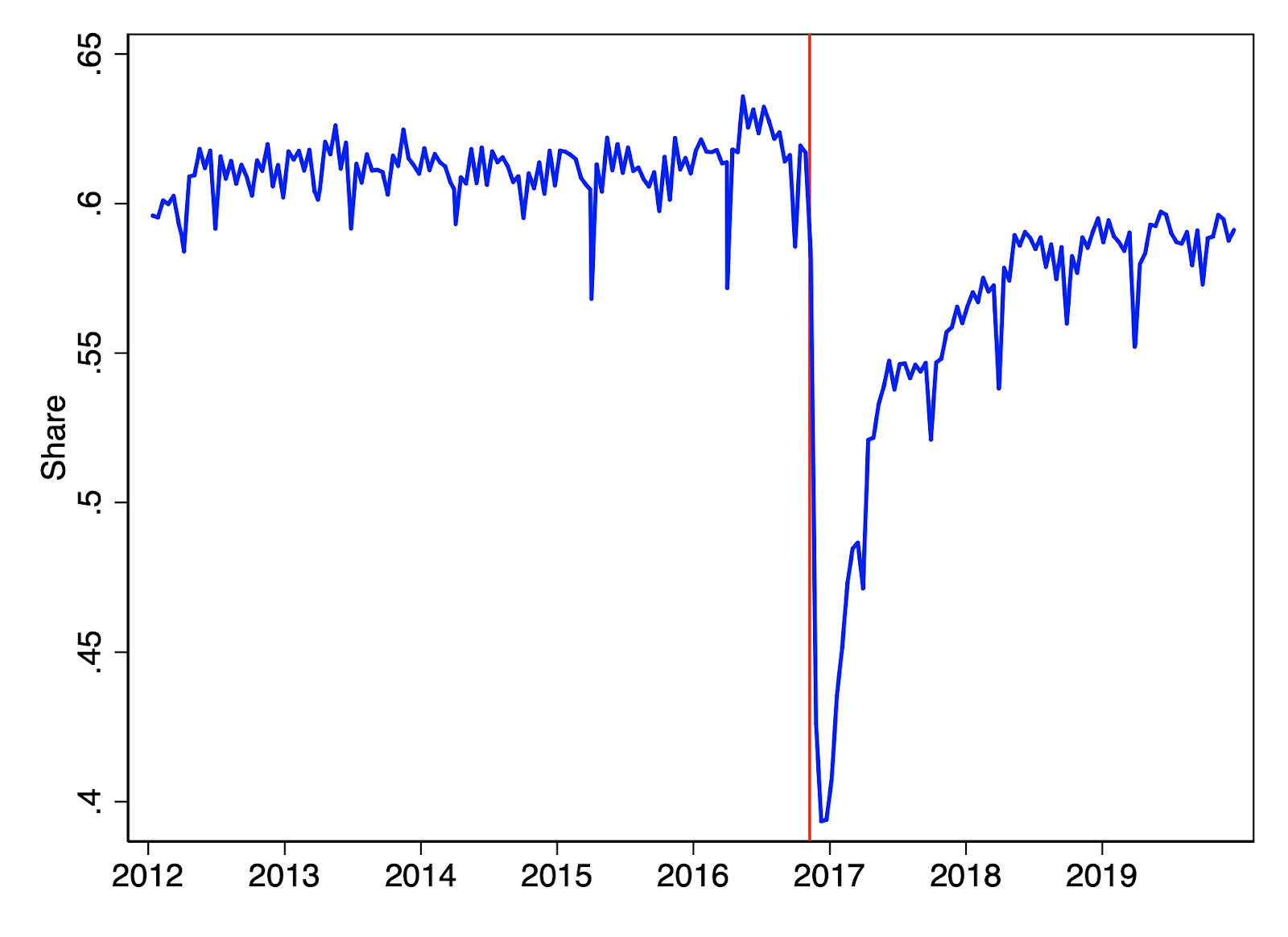

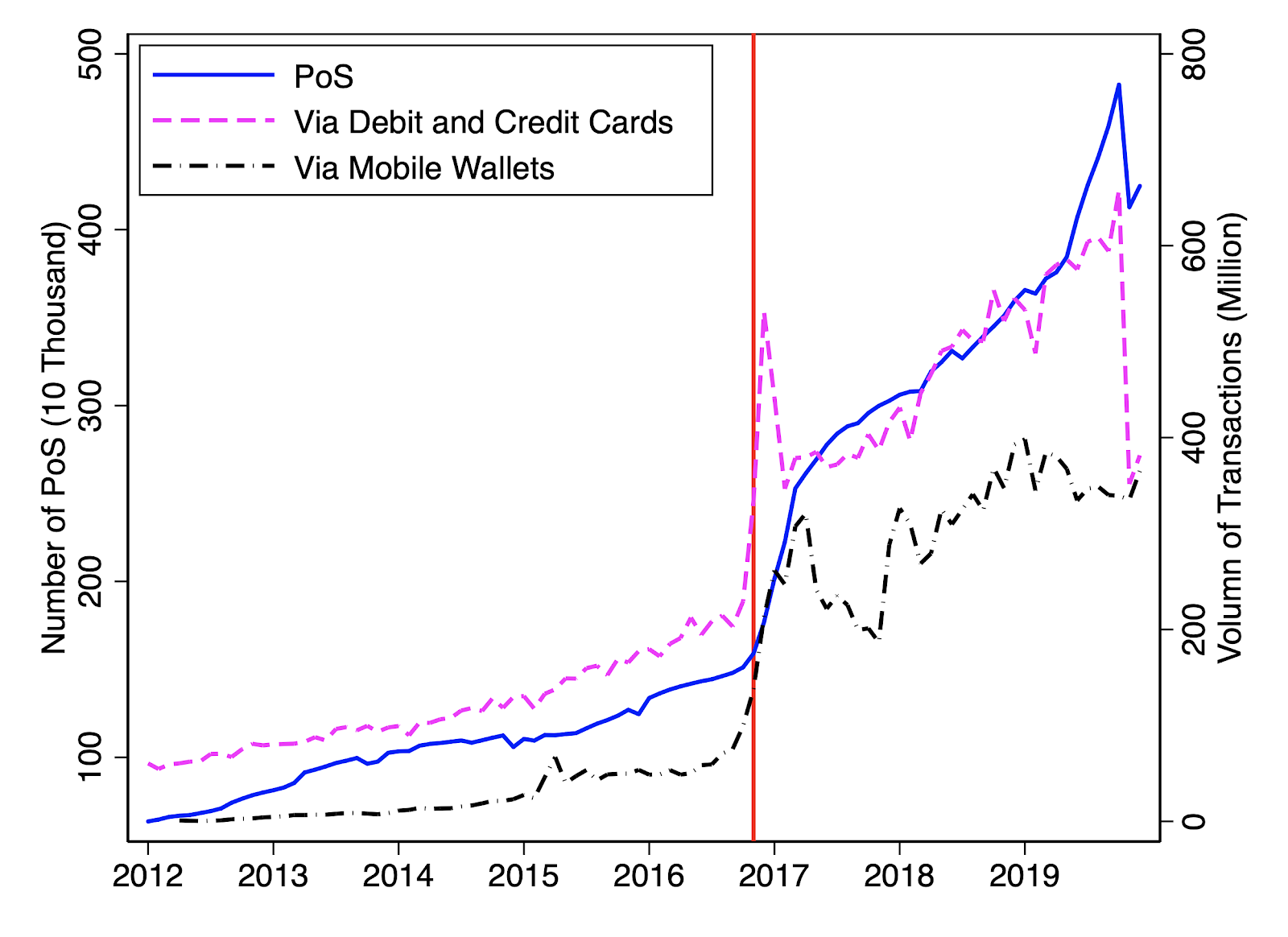

On 8 November 2016, the Government of India unexpectedly invalidated Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 notes, removing 86% of cash from circulation overnight. Intended to curb black money and promote formalisation (Lahiri 2020), the policy also triggered an unprecedented shift toward digital payments. Debit and credit card transactions surged, and mobile wallets proliferated. Figure 1a shows the sharp drop of in the amount of currency held by the public and Figure 1b shows the increase in digital payment after the policy shock.

Figure 1. Trends of currency in circulation and digital transactions

(a) Currency with the public as a share of ‘narrow money’

Notes: (i) Panel (a) shows the share of currency with the public in narrow money (M1), based on monthly data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Monthly Bulletin. Currency with the public is total currency in circulation minus cash held by banks. (ii) Panel (b) plots trends in digital transactions: the number of point-of-sale (PoS) terminals (blue), card transactions (purple), and mobile wallet transactions (black). (iii) The red vertical line marks November 2016, when demonetisation was announced.

Yet not all regions were equally prepared to embrace this shift. Firms’ ability to adapt depended on their local digital readiness – the availability of internet infrastructure, mobile networks, and digitally skilled workers. To capture this variation, I construct a district-level e-Readiness Index, based on the framework developed by India’s Department of Electronics and Information Technology and the National Council of Applied Economic Research. The index combines indicators of ICT (information and communications technology) infrastructure (for example, internet penetration, mobile coverage, and telecom establishments) and stakeholder preparedness (for example, households with computers and firms engaged in ICT activities). Districts with higher scores were better positioned to adopt digital technologies before demonetisation.

Data and methodology

The analysis draws on two datasets from the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE). First, the Prowess database provides annual financial statements for more than 30,000 formal-sector firms across India between 2012 and 2019, allowing me to track income, sales, assets, and investments in ICT capital such as software, computers, and IT systems. Second, the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS), a nationally representative household panel, records employment, education, and wages and enables identification of workers with ICT-related degrees (for example, engineering or computer science) and tracking their wages and sectoral employment before and after demonetisation.

To estimate the causal effects of digitalisation, I use a ‘difference-in-differences’ design that compares firms in districts with high versus low e-Readiness index before and after the 2016 demonetisation. I also control for local factors such as bank branch density, ATM availability, and nighttime light intensity, which serve as proxies for financial access and regional economic activity.

What happened? A widening gap between services and manufacturing

The results reveal that digitalisation’s effects were far from uniform across sectors. On average, firms in more digitally prepared districts did not significantly outperform others after the 2016 shock. However, breaking the results down by sector shows a stark divergence:

- Service-sector firms in districts with one standard deviation higher e-Readiness index experienced a 1.3% increase in income and an 8.4% rise in total factor revenue productivity (TFPR) after demonetiszation.

- Manufacturing firms, in contrast, saw a 2.5% decline in income and an 8.1% drop in TFPR over the same period.

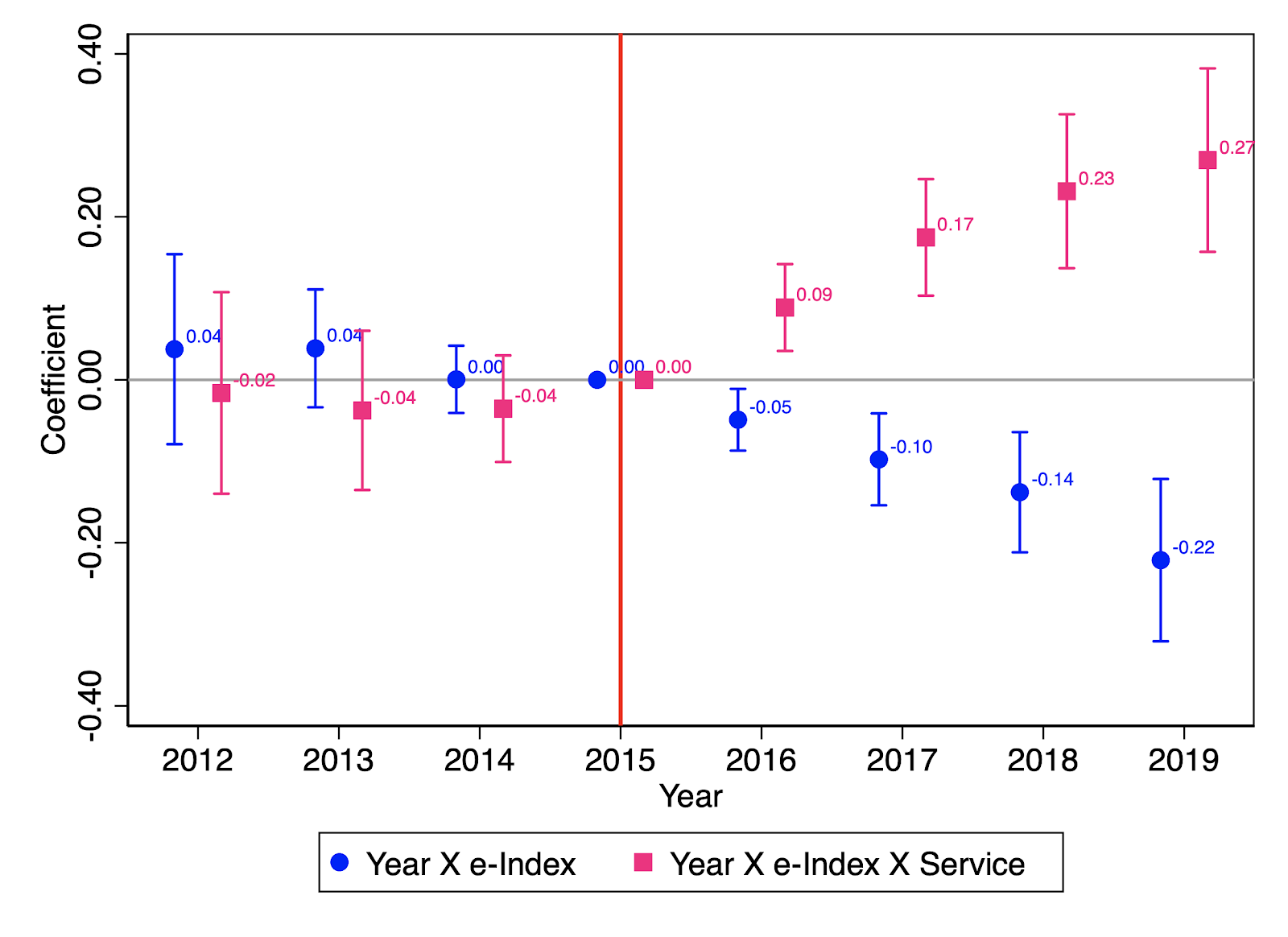

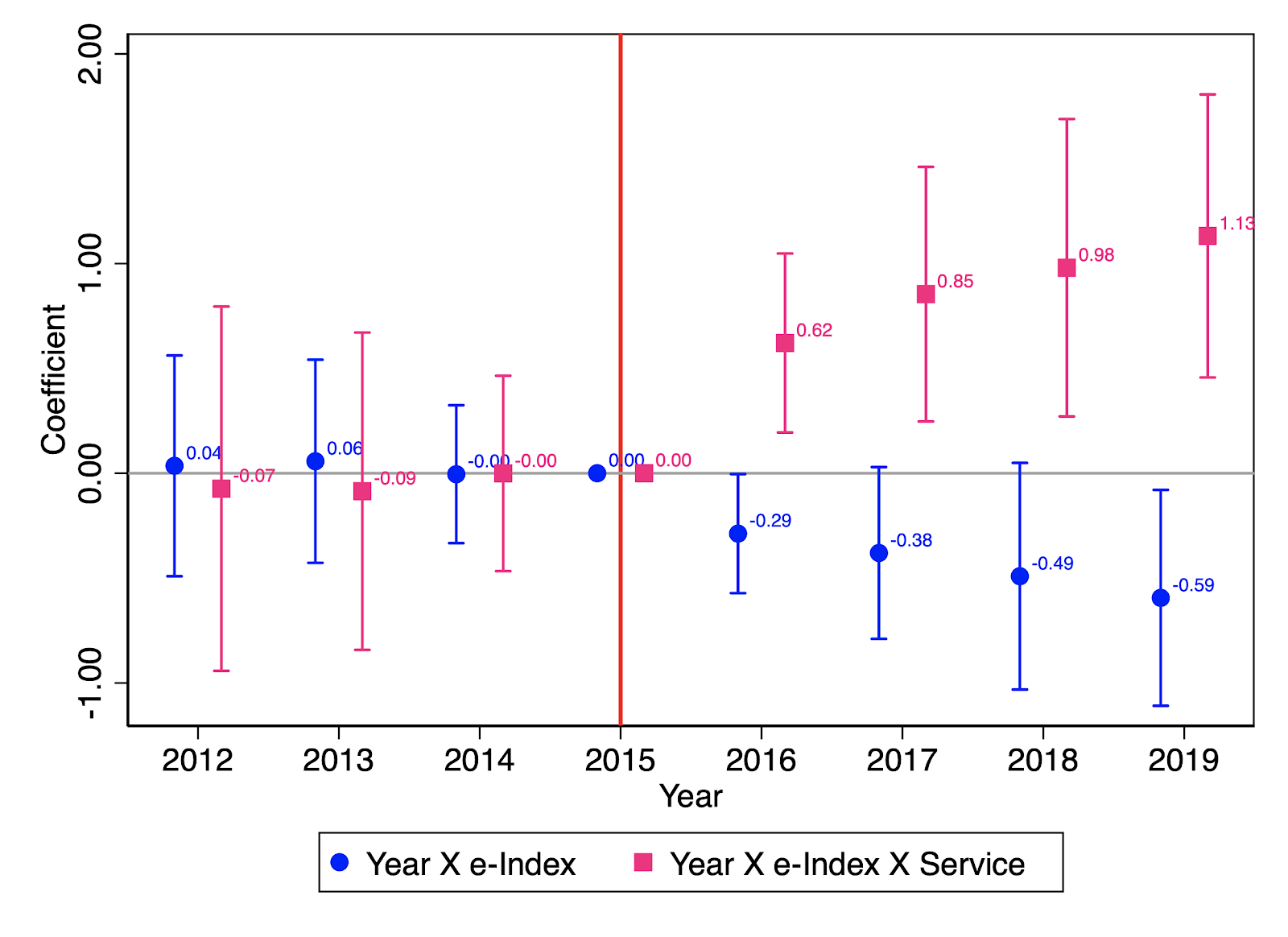

In other words, the same digital push produced winners and losers: services adapted and expanded, while manufacturing contracted. Figure 2 clearly shows the divergent trends, with manufacturing trending downward after 2016 and services, relative to manufacturing, trending upward in more e-Ready districts.

Figure 2. Divergent effects of digitalisation on manufacturing and services after Demonetisation

(a) Log (Income)

Notes: (i) The figure shows estimated year-by-year effects of digitalisation (measured by the district-level e-Readiness Index) on firms’ income and total factor revenue productivity before and after the 2016 demonetisation. (ii) Blue circles represent the effects on manufacturing firms (Year X e-Index interaction terms), and pink squares represent the additional differential effects on service firms relative to manufacturing firms (Year X e-Index X Service interaction terms). (iii) The red vertical line indicates the base year (2015), the year before demonetisation. (iv) Confidence intervals are shown at the 95% level. A 95% confidence interval means that, if you were to repeat the experiment with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated confidence interval would contain the true effect.

Why services surged while manufacturing stumbled

The study’s evidence points to a key mechanism: the scarcity and limited geographic mobility of ICT labour, combined with the complementarity between ICT labour and ICT capital. Digital adoption depends on these two complementary inputs, and firms cannot effectively operate new technologies without the skilled workers needed to install, integrate, and maintain them.

After demonetisation, demand for ICT labour rose sharply as firms were incentivised to shift to digital payments and online systems, particularly in districts with stronger digital infrastructure. However, the supply of ICT labour is both limited and geographically immobile. Engineering enrolment did not expand in the years leading up to the shock, and migration rates for economic reasons remain low. As a result, local labour markets could not adjust, and ICT workers could not flow into districts where digitalisation pressures were greatest.

My data analysis shows that:

- In districts with one standard deviation higher e-Readiness index, wages for ICT professionals rose by about 8.7%, while wages for other workers remained flat, widening the wage gap between ICT and non-ICT workers.

- ICT workers moved toward the service sector: they were 2.6% more likely to join the service sector and 2.4% less likely to work in the manufacturing sector after 2016 in districts with one standard deviation higher e-Readiness index. At the same time, low-skill workers became more likely to work in manufacturing.

- Service firms increased investments in ICT assets and digital services, while manufacturing firms cut back on such investments and substituted toward lower-skill labour.

Taken together, service firms adopted digital technologies and improved productivity, while manufacturing firms – facing a shortage of skilled workers – reduced ICT investment, shifted toward low-skill labour, and experienced productivity declines.

Alternative explanations

The study also evaluates three alternative channels. A pure demand-side explanation would predict stronger service-sector gains in districts hit harder by the cash shortage, yet service firms in more digitally ready districts show no systematic variation with shock severity. Liquidity constraints or supply-chain disruptions would be expected to cause short-lived effects concentrated among exporters (mostly manufacturing), but the manufacturing decline persists through 2019, remains after excluding pre-2016 exporters, and does not appear in working capital (that is, a liquidity proxy). Spillovers from informal agriculture or construction also find little support, as formal firms in these sectors do not perform notably worse in more e-Ready districts. Taken together, these patterns indicate that these alternative mechanisms are unlikely to account for the observed sectoral divergence.

Policy implications

India’s experience illustrates that digitalisation does not automatically generate broad-based gains. When key inputs such as skills and infrastructure are unevenly distributed, digital shocks can widen existing structural divides. To ensure that digitalisation supports inclusive growth, infrastructure, institutions, and inclusion must advance together.

- Invest in digital skills at scale. Expanding access to computer science, engineering, and vocational training beyond metropolitan areas can help alleviate skill shortages.

- Facilitate labour mobility. Policies addressing housing, transport, and inter-state certification can enable skilled workers to move where they are needed most.

- Support digital adoption in manufacturing. Targeted credit, tax incentives, and shared ICT platforms can help small and medium enterprises integrate digital tools without displacing labour.

- Strengthen digital infrastructure in less developed areas. Improving connectivity and technological readiness in lagging regions is essential for balanced regional growth.

Further Reading

- Agarwal, Sumit, Wenlan Qian, Bernard Yeung and Xin Zou (2019), “Mobile wallet and entrepreneurial growth,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 48-53. Available here.

- Chen, Yutong (2025), “Digitalization as a double-edged sword: Winning services and losing manufacturing in India,” Journal of Development Economics, 103618. Available here.

- Colecchia, Alessandra and Paul Schreyer (2002), “ICT investment and economic growth in the 1990s: Is the United States a unique case? A comparative study of nine OECD countries,” Review of Economic Dynamics, 5(2): 408-442. Available here.

- Lahiri, Amartya (2020), “The great Indian demonetization,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1): 55-74.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)