In the sixth post of I4I’s month-long campaign to mark International Women’s Day 2023, Vijaya at al. investigate mobility constraints among college-going students in Jalandhar. They find that while a greater proportion of boys are allowed to travel on their own earlier in life, this gender gap reduces by the time they reach college, and that more girls gain the freedom to travel in households where adult women already travel alone. They also investigate how gender, caste and class-based differences intersect to affect access to mobility: impacting time and distances travelled.

Join the conversation using #Ideas4Women

Women’s mobility has increasingly been cited as an important factor in influencing women’s labour force participation in India (Lei et al. 2019, Chatterjee and Sircar 2021). While some urban governments have experimented with free or discounted public transportation for women and some research studies have focussed on transport infrastructure, mobility constraints are not impacted by the availability of transport options alone – they are a complex combination of safety, gender norms, and the intersection of gender with caste and class based geographical segregation.

In a recent study we trace the development of these varied facets by exploring the travel experiences of a group of college students. Looking at this cohort provides insight into gender differences in access to spaces and opportunities that are often seen in early adulthood.

Study sample

Our study is based on a survey of students at a college in Jalandhar, Punjab. The college has several locational advantages, including being on a national highway near the Jalandhar cantonment and close to a bus stand. The college has historically been committed to expanding free education for Dalit students and has a stated core value of expanding education for women. Therefore, relative to other colleges, our sample works out to have high levels of representation of women and Dalit (including Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) students. Women make up 55% of our current respondents, whereas nearly 52% identified as Dalit.

The initial findings discussed here are based on our first round of 101 respondents, primarily first year undergraduate students who participated in our study to share information on their travel experiences on a voluntary basis, from October 2021 to May 2022. While this is preliminary data, the combination of information on lifecycle transition, and intergenerational information generated insights which can further the discussion and provide a framework for more resourced data collection efforts. We also use locational coordinates to examine the spatial dimensions of access to opportunities for urban, semi-urban, and rural youth. This enables us to examine the intersectionality of gender with caste and class based geographical isolation.

Gender differences in freedom to travel

The prevalence of restrictive gender norms across varied dimensions has been well documented in surveys and research (Agarwal 1997, Jayachandran 2021). We go beyond a static view, and trace the evolution of gender differences in autonomy regarding mobility. In our cohort we see that the transition from school to college does improve freedom of movement for girls. In Table 1, only about 18% were allowed to travel on their own anywhere other than school, compared to about 43% for boys. This substantial gender difference prior to college is statistically significant. However, by the time they get to college, a little over 40% of girls are allowed to travel on their own anywhere. In this case, even though boys did report a small improvement in their freedoms, the gender difference is not statistically significant. By the time they reach college, more than half the boys (56%) identified as having full freedom to travel alone, compared to the 43% who had this freedom when they were in school. Going to college therefore does seem to reduce the gender gap in mobility.

Table 1. Effect of gender on the freedom to travel alone

|

Gender |

Always Accompanied |

Alone Only to School/College |

Alone Anywhere |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Allowed to travel alone before college (in %) |

|||

|

Girls |

26.3 |

55.5 |

18.2 |

|

Boys |

13 |

43.5 |

43.5 |

|

Allowed to travel alone while in college (in %) |

|||

|

Girls |

10.5 |

47.2 |

42.1 |

|

Boys |

0 |

43.5 |

56.5 |

Note: These figures are statistically significant at the 90% level.

In Table 2 we see the intergenerational impact of gender norms. In households where adult women travel alone, a greater proportion of girls gain freedom to travel in college. In such households, 48% of girls are now able to travel alone anywhere. In contrast only 28% of girls from families where adult women do not travel alone gain such freedom in college. For boys, interestingly, the reverse is true – while 73% of boys in households with restrictions on adult women can travel alone anywhere, only 33% of boys in household where adult women travel alone have that freedom. These differences are statistically significant. One potential explanation for this substantial difference is that in households where adult women do not travel alone, there is greater reliance on boy for running errands outside the house. That the presence or absence of patriarchal norms within households impacts both boys and girls in different ways while not a surprise, bears more exploration.

Table 2. Effect of household gender norms on the freedom to travel alone while in college

|

Restrictions on Women in Household |

Always Accompanied |

Alone Only to School |

Alone Anywhere |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Percentage of girls allowed to travel alone |

|||

|

Travel Alone |

0 |

51.9 |

48.2 |

|

Do not Travel Alone |

12 |

60 |

28 |

|

Percentage of boys allowed to travel alone |

|||

|

Travel Alone |

0 |

66.7 |

33.3 |

|

Do Not travel Alone |

3.9 |

23.1 |

73.1 |

Note: These figures are statistically significant at the 90% level

Gendered effects of access to transportation and accommodation

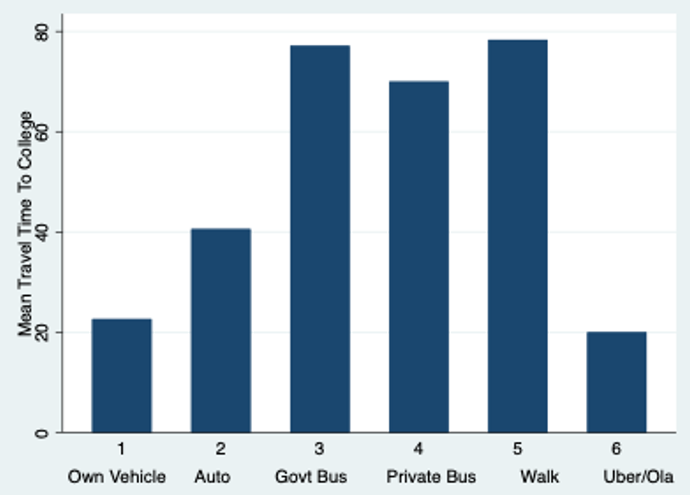

Next, we turn to the impact of different transport options available to boys and girls. About 35% of students commuted in their own vehicle. In Figure 1 we see the average commute times for the different modes of travel. Those traveling by a private vehicle, whether their own or through private taxis such as Uber or Ola had the lowest average commute time, whereas those dependent on buses had the highest, with an average commute time of over an hour each way.

Figure 1. Average commute time by private and public vehicles, in minutes

There is a substantial difference in the transport choices available to boys compared to girls. While 42% of boys used their own vehicle for commuting, only 30% of girls traveled by their own vehicle. Nearly 48% of girls travelled by buses (compared to just 30% for boys). As a result, the average commute time is substantially longer for girls.

Female students’ greater dependence on buses has several implications. Household assets like vehicles are likely prioritised for the use of men and boys. From qualitative responses we also gathered that some female students travelled together in buses, potentially for safety reasons. In winter months when wait and commute times are longer due to fog, girls are more likely to miss the first two classes. Similarly, they also tended to leave earlier – missing afternoon classes – to catch an earlier bus, since parents tend to worry more. Some girls also reported travelling long distances from neighbouring semi-urban and rural areas, since parents considered hostels or other accommodation within the city unsafe.

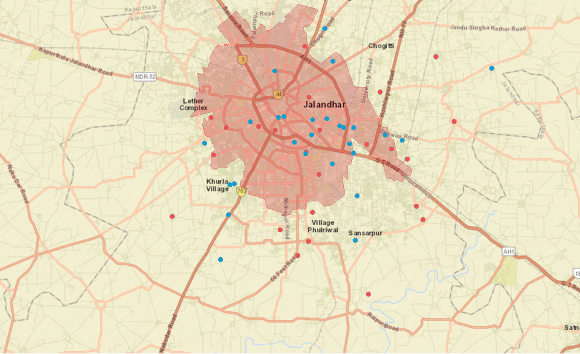

We used GIS mapping to assess this locational factor. In Figure 2, we see that male students tend to be more concentrated in the core city. Locations of female students are more widespread into the adjoining semi-urban areas. The influence of locational disadvantages on economic outcomes has received attention in economic research, particularly in developed economies (Chetty et al. 2014). Here we see the gendered and other intersectional elements of spatial disadvantages. For example, in Figure 3 we also see that the spread of students tracks socio-economic status based on caste and income. In our survey we gather information on caste, religion, and household income. In the initial analysis we focus on caste and income status, and find that students from Dalit backgrounds and those from households with below median income levels are relatively more spread away from the core city (see Figure 3). Given this geographical segregation, Dalit students as a group had higher commute times, with an average of about 60 minutes of travel each way.

Figure 2. Distribution of students across Jalandhar by gender

Figure 3. Distribution of students across Jalandhar by caste and income

Notes: i) Red crosses represent SC/ST students; green crosses represent OBC students, blue crosses represent students from the general category. ii) Blue dots represent students from households with above median income, while red dots represent students from households with below median income

Conclusion

We find that gender norms around mobility change during major lifecycle transitions – for example, going to college does expand travel autonomy for about 40% of the girls in our cohort. However, a much higher proportion of boys gain travel freedoms even before college, and they continue to expand on these freedoms in college. There is also an intergenerational impact of gender norms: maternal agency and access to mobility correlates to changes in travel freedoms of both girls and boys in college.

In these results we see the tenuous dynamic between gender and mobility. We find that college does expand some horizons for girls. However, additional challenges like generationally restrictive gender norms, fewer choices for mode of travel, heightened safety concerns, and greater geographical isolation from opportunities limit the progress towards greater autonomy.

Further Reading

- Agarwal, Bina (1997), “Bargaining” and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond Households”, Feminist Economics, 3(1): 1-51. Available here.

- Chatterjee, Deepaboli and Neelanjan Sircar (2021), “Why is Female Labour Force Participation So Low in India?”, Urbanization, 6(1): S40-57.

- Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline and Emmanuel Saez (2014), “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4): 1553-1623.

- Jayachandran, Seema (2021), “Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries”, International Monetary Fund Economic Review, 69(3): 576-595.

- Lei, Lei, Sonalde Desai and Reeve Vanneman (2019), “The Impact of Transport Infrastructure of Women’s Employment in India”, Feminist Economics, 25(4): 95-125.

16 March, 2023

16 March, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.