Although women’s education has been proposed as a solution to the persistent issue of ‘missing girls’ in India, studies have reached contradictory conclusions on the impact of female education on child sex ratios. Drawing on sub-district-level Census data from 2001 and 2011, this article shows that mothers with more education have fewer daughters – but these girls are also more likely to survive.

According to the 2011 Census of India, the country’s overall female-to-male ratio has increased since the 2001 Census – from 933 to 940 women per 1,000 men. These improvements in India’s overall sex ratio have led to claims that the war on baby girls is “winding down” (The Economist, 2017, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 2011). Sex-ratio gains, however, hide the fact that, in India, the child sex ratio continued to decline over the same period, indicating that the ‘missing girls’ problem is still a pressing concern. Are girls missing all over India? And, is educating women a possible route to improving sex ratios?

Child sex ratios across states, over time

Women’s education has been proposed as a solution to the missing girls problem (Bourne and Walker 1991, Inchani and Lai 2008). However, studies on women’s education and child sex ratios have reached contradictory conclusions (see Bhalotra and Cochrane 2010). Educating women has been found to worsen child sex ratios, because women with more education – who want to have fewer children overall, but want a son – are more likely to abort girl children (Mayer 1999, Das Gupta and Mari Bhat 1997). Others have observed that education for women improves sex ratios, because girl children of women who are educated are more likely to survive (Bourne and Walker 1991, Inchani and Lai 2008).

What is the current relationship between advances in women’s education and child sex ratios in India? We address this question by analysing recent, comprehensive, and disaggregated Census data from across India (Chhibber, Jensenius and Ostermann 2021).

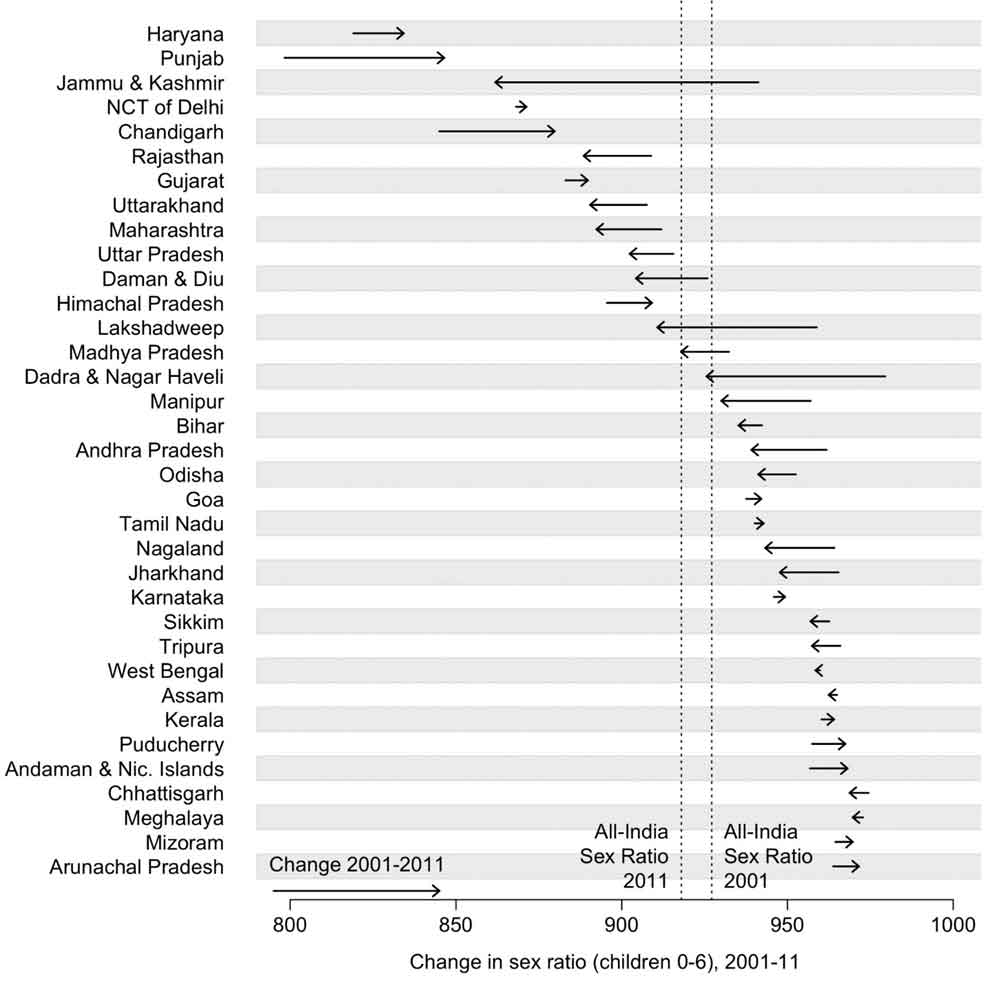

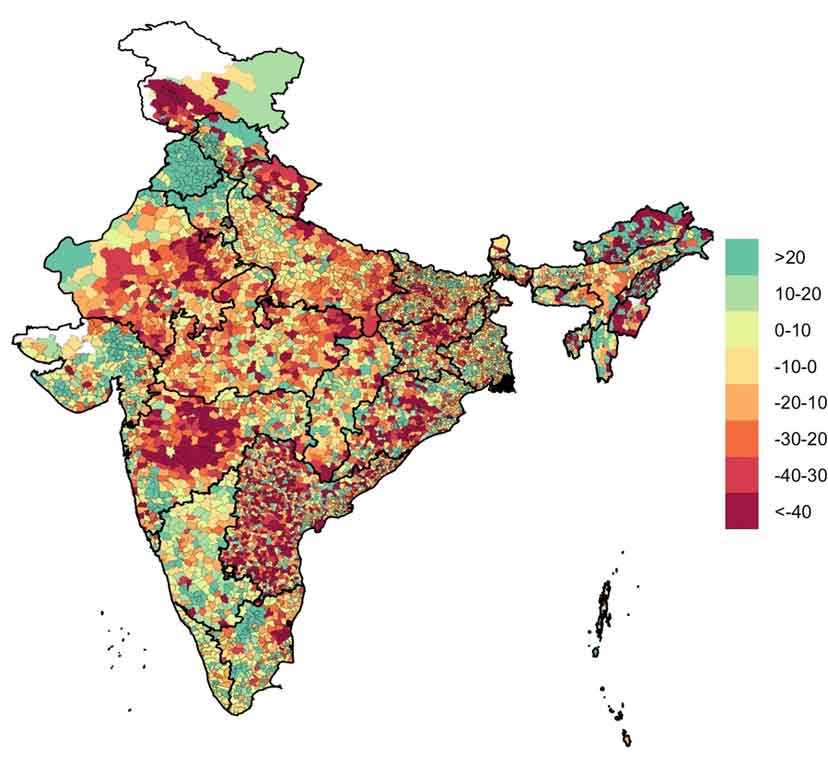

The map in Figure 1 draws on data from the 2011 Census of India to show the sex ratio among children aged 0-6 years across India’s sub-districts. The areas marked in shades of green – those with sex ratios greater than 975 – are clustered in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and the Northeast. The areas marked in reds are mostly in the northern and western parts of India, in states such as Haryana and Punjab that are infamous for their low sex ratios, but also in other large states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh.

Figure 1. Sub-district-level child sex ratio

To some extent, this pattern confirms the north-south divide that Dyson and Moore (1983) established using 1901-1981 Census data. However, the pattern has been weakened by recent trends, as shown in the map in Figure 2. The worst-offender states have improved since 2001: both Haryana and Punjab had higher child sex ratios in 2011 than in 2001. However, there were significant declines elsewhere – in Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. It is also no longer true that South India does not have a missing-girls problem.

Figure 2. Change in child sex ratios between 2001 and 2011

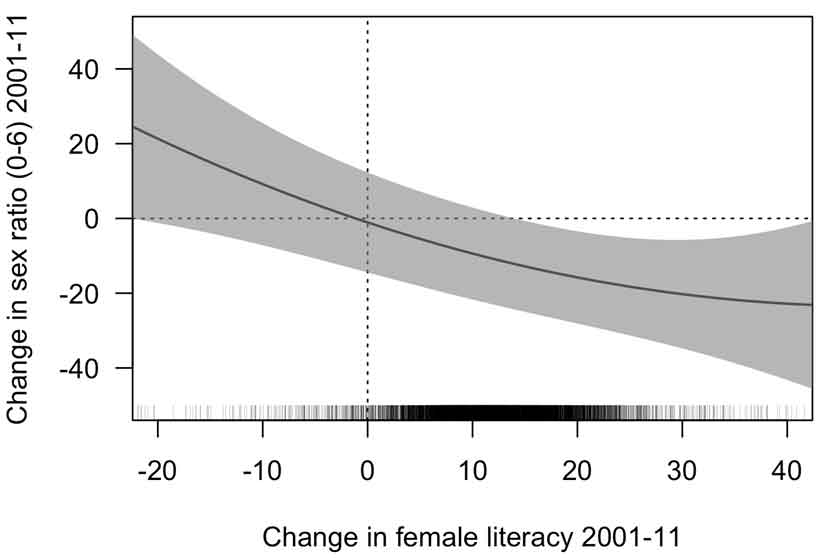

State-wise changes in child sex ratios between 2001 and 2011 are shown in Figure 3. The grey dotted vertical lines indicate the average state-wise sex ratio of 927 in 2001 and 918 in 2011, indicating an overall decline of about 9 points. For each state, we show the change between 2001 and 2011 with an arrow. The states are arranged in ascending order according to their values in 2011, with Haryana on top, with a sex ratio of 834 in 2011 (up from 819 in 2001), and Punjab in second place, with a sex ratio of 846 (up from 798 in 2001). Figure 3 demonstrates how sex ratios have worsened in states like Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and several Northeastern states. Few states, other than Haryana, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh, experienced major improvements over this period.

Figure 3. State-wise changes in child sex ratios between 2001 and 2011

Note: The starting point of the arrow indicates the value in 2001 and the arrowhead shows the value in 2011.

Does women’s education impact child sex ratios?

Knowing that child sex ratios worsened from 2001 to 2011, we turn to our next question: will increases in women’s education influence the ratio of girls to boys? Literature from the past few decades provides evidence that women’s education in India is associated with lower female fertility (Reddy 2003), the number of children a woman has, and higher female mortality (Mayer 1999, Das Gupta and Mari Bhat 1997), the frequency of women’s deaths. To explore whether these trends are still present, we examine data from the fertility series of the 2011 Census. These data cover all women in India (approximately 587 million individuals), and include information about the number of children born to women with different levels of education. As it is not obvious how to rank-order all of the original educational categories, we collapse the information about women’s educational attainment into four categories: ‘illiterate’, ‘literate or completed primary school’, ‘completed middle school, secondary school, or entered university without graduating’, and ‘graduate or above’.

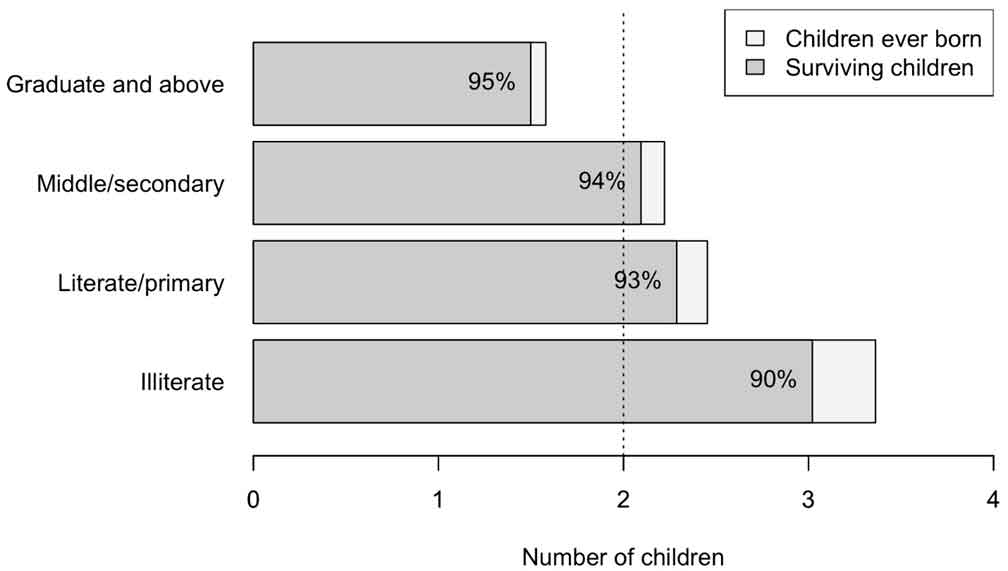

Consistent with previous findings, we find a strong association between women’s education level, fertility, and the mortality of their children. Figure 4 shows the average number of children born to married women aged 30-44 years, of various education levels, and the number of these children who were still alive at the time of data collection. We choose to present data for women aged 30-44 years because they entered their child-bearing years after the 1980s, when sex-selective abortion became widely available – though illegal – in India, and were also old enough to have had several children. These criteria reduced the dataset to approximately 121 million women.

Figure 4. Number of children of married women aged 30-44 years, across education levels

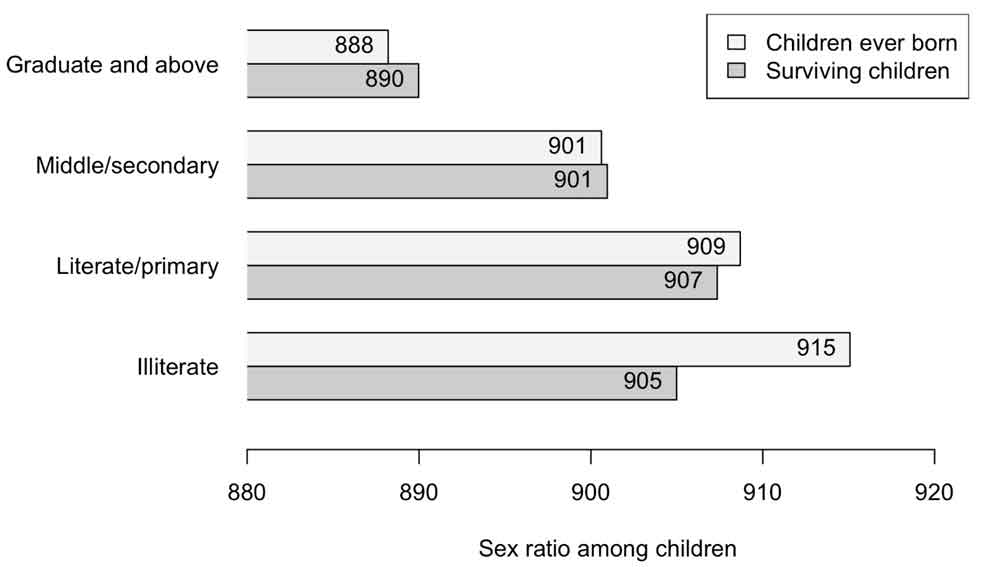

We also identify a relationship between women’s education and the sex ratio of their children. Figure 5 shows the sex ratios of all children born to mothers aged 30-44 years, and also the sex ratios of their surviving children. Here, we see quite clearly both the positive and negative associations between women’s education and child sex ratios found in earlier work (Bourne and Walker 1991, Bhalotra and Cochran 2010, Echávarri and Ezcurra 2010, Mayer 1999, Murthi, Guio, and Drèze 1995).

The light grey bars indicate a strong negative relationship between a mother’s educational attainment and the sex ratio of the children born to her, with educated women – university graduates in particular – having fewer girl children. Importantly, the difference is not only between literate and illiterate women: the higher the educational level of the mother, the fewer the girls she bears. However, the difference between each pair of light gray and dark gray bars in Figure 5 show a difference in survival rates by the education level of mothers – whereas the girls born to educated mothers are as likely to survive as their brothers, the survival rate of girls born to illiterate mothers is much lower. This suggests that female infanticide and neglect are of particular concern among illiterate mothers.

Figure 5. Sex ratio of children of married women aged 30-44 years, across education levels

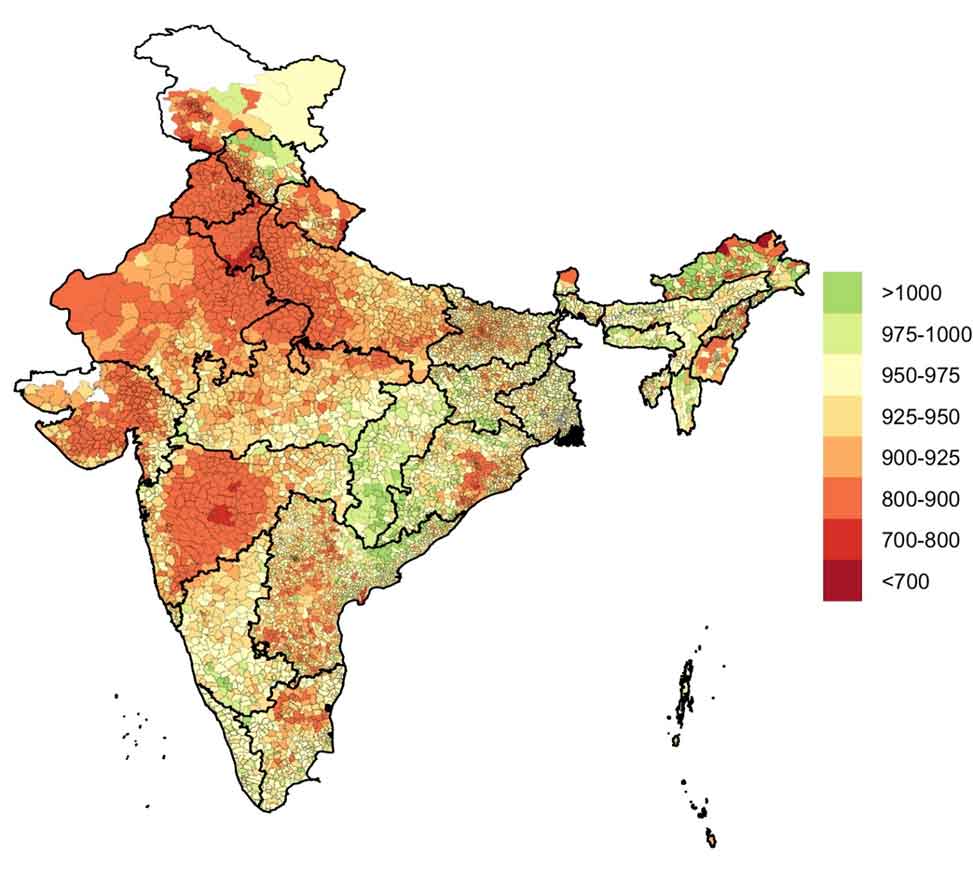

Finally, we ask if the change in women’s literacy between 2001 and 2011 is associated with the reduction in child sex ratios that we see in India during this period? We use sub-district-level Census data from 2001 and 2011 to estimate a ‘change model’ and find that sub-districts that experienced an increase in female literacy from 2001 to 2011 were also, on average, more likely to see a decrease in their sex ratio during this period. This negative association predicted from our model is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Predicted changes in female literacy and sex ratios

Notes: (i) The vertical lines at the bottom of the plots indicate the location of the underlying sub-district-level observations. (ii) The shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors.

Policy implications

Our analysis shows that, overall, local-level increases in female literacy are negatively associated with child sex ratios. Although the survival rate of girls born to educated women is higher, this positive trend does not offset the negative trend of educated mothers choosing to abort girl children. Our findings indicate the need for at least two distinct policy approaches to combat the problem of missing girls: among educated women, printed materials and the educational system can be used to challenge cultural preferences for sons, since the main goal should be to discourage sex-selective abortions. On the other hand, among the less-educated population, particularly the illiterate, governments should focus on economic or – in light of Anukriti (2018) that demonstrates that financial incentives do not necessarily have desired effects – other rewards for better treatment of girls in order to increase their survival rates.

I4I is now on Telegram. Please click here (@Ideas4India) to subscribe to our channel for quick updates on our content.

Further Reading

- Anukriti, S (2018), “Financial Incentives and the Fertility–Sex Ratio Trade-off”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(2): 27-57.

- Anukriti, S (2018), ‘Financial incentives and the fertility-sex ratio trade-off in India’, Ideas for India, 25 June.

- Bhalotra, S and T Cochrane (2010), ‘Where have all the young girls gone? Identification of sex selection in India’, The Centre for Market and Public Organisation, Working paper 10/254.

- Bourne, Katherine L and George M Walker Jr (1991), “The Differential Effect of Mothers’ Education on Mortality of Boys and Girls in India”, Population Studies, 45(2): 203-219. Available here.

- Chhibber, Pradeep, Francesca R Jensenius and Susan L Ostermann (2021), “Missing Girls: Women’s Education and Declining Child Sex Ratios in India”, Economic and Political Weekly, 56(6).

- Das Gupta, Monica and PN Mari Bhat (1997), “Fertility Decline and Increased Manifestation of Sex Bias in India”, Population Studies, 51(3): 307-315. Available here.

- Dyson, Tim and Mick Moore (1983), “On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India”, Population and Development Review, 9(1): 35-60. Available here.

- Echávarri, Rebeca A and Roberto Ezcurra (2010), “Education and Gender Bias in the Sex Ratio at Birth: Evidence from India”, Demography, 47(1): 249-268. Available here.

- Inchani, Lisa R and Dejian Lai (2008), “Association of Educational Level and Child Sex Ratio in Rural and Urban India”, Social Indicators Research, 86(1): 69-81. Available here.

- Mayer, Peter (1999), “India’s Falling Sex Ratios”, Population and Development Review, 25(2): 323-343. Available here.

- Murthi, Mamta, Anne-Catherine Guio and Jean Dreze (1995), “Mortality, Fertility, and Gender Bias in India: A District-level Analysis”, Population and Development Review, 21(4): 745-782. Available here.

- Reddy, PH (2003), “Women’s Education and Human Fertility in India”, Social Change, 33(4): 52-64. Available here.

- The Economist (2017), ‘Gendercide: The War on Baby Girls Winds Down’, 21 January.

- UNFPA (2011), ‘Report of the International Workshop on Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth: Addressing the Issue and the Way Forward’, Report.

30 June, 2021

30 June, 2021

By: Beverly 14 July, 2021

Education is transformative for poor Indian girls in particular. The fact remains, though, that educated, affluent Indian families abort their girls far more aggressively. The seeming contradiction reveals that while affluent women may have education, position, and even professional jobs, they remain subordinate to the men within their own families. Wealthy families can be highly patriarchal, perpetuating the strong preference for sons over daughters -- whether due to dowry considerations, inheritance concerns, continuation of the family name, or the desire to have a son perform funeral rites.