While “child penalties” for women in the labour market are well-documented in high- and middle-income countries, how the events of marriage and childbirth play out for women in largely informal economies is relatively understudied. Analysing data from rural Rajasthan and Karnataka, this article finds that married women continue to work following the birth of their first child – a marker of necessity-driven participation in low-paying informal jobs.

Marriage and childbirth are transformative life events for women, with significant labour market implications. A marriage premium for men and child penalties for women has been well-documented in high- and middle-income countries (Juhn and McCue 2017, Kleven et al. 2023). However, how these events play out for women in largely informal economies is relatively understudied. In our recent research, we ask a simple but important question: how are marriage and childbirth related to women’s employment? (Lahoti, Abraham and Swaminathan 2024)

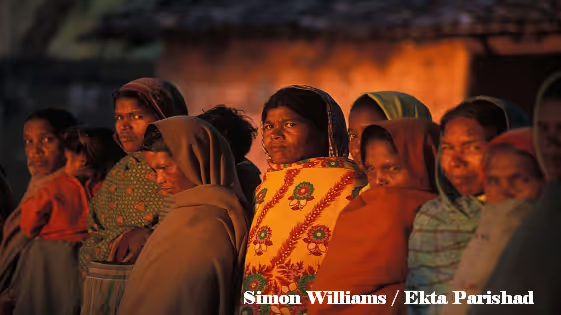

The study context is rural India, is predominantly an informal and agriculture-dependent economy, in contrast to the formal, non-agricultural economy of developed countries. About 87% of the rural workforce in India is in informal employment, which includes self-employment and casual wage employment in agriculture. Marriage and childbirth occur substantially earlier in life in rural India than in high- and middle-income countries. Much of India is patriarchal with relatively rigid gender norms that govern men's and women’s roles in the household and social settings. Residence patterns are patrilocal, where a woman migrates to her husband’s home after marriage. Together, these have implications for women’s employment before marriage and after childbirth.

Contribution to the literature

The extensive literature on women’s labour market participation in India spans a range of topics but has not seen a systematic treatment of the impact of marriage and childbirth. Of the two life events, childbirth and its interactions with the labour market have been relatively more researched. Most studies on this topic have used cross-sectional observational data including a ‘binary’ for the presence of children in the household. Das and Zumbyte (2017), for instance, find that younger children in the household are negatively associated with urban women’s labour supply. More recently, Deshpande and Singh (2021) compare parents and non-parents to investigate the impact of motherhood on labour market participation, and do not find any immediate effect of childbirth.

In terms of methods, event study is most commonly used in the child penalty literature. However the existing research has primarily focused on high- and middle-income countries (Kleven et al. 2019, Berniell et al. 2023). Kleven et al. (2023) use a pseudo-event study and jointly estimate the impact of marriage and childbirth across various developing countries. However, data limitations in the Indian context prevent a precise estimation of the marriage effect. Our study, using a Life History Calendar, addresses this gap in the data.

Our study contributes in three main ways. First, we provide rare causal evidence on how marriage itself – independent of childbirth – shapes women’s employment in a low-income, highly informal setting, using life-history data and a joint event-study design that separately identifies the effects of marriage and first birth. Second, we add to the emerging literature on “child penalties” at low levels of development, showing that in rural India fertility has little impact on women’s aggregate labour supply even as marriage sharply increases women’s participation. Third, we speak to debates on India’s low female labour force participation by bringing a life-course perspective that highlights how norms around unmarried women’s employment, early marriage, and the structure of rural labour markets jointly generate the observed trajectories.

The Life History Calendar

Ideally, if we wanted to isolate the impact of an event on an outcome, in this case, marriage or childbirth on women’s employment, we should have data for women before and after the events. A key challenge, particularly in low-income countries is the lack of long-term panel data. To address this, we use a Life History Calendar (LHC) approach, implemented as part of the 2020 India Working Survey (IWS) conducted in rural Karnataka and Rajasthan. The Life History Calendar is a paper-based survey where we record for every respondent from age 15 onwards, their marital status, childbirths, and labour market status, including paid work (formal and informal) and unpaid work on family farms or enterprises, for every year. In this way, we are able to construct a retrospective panel that identifies when respondents got married, had children, and their employment status and type in each year from the age of 15.

We focus on the impact of two key events: (i) marriage, and (ii) first childbirth. To estimate how these events change employment outcomes, we use an event-study framework, tracking the same women from five years before to five years after each event. Since marriage and childbirth often occur close together, we implement a joint event study approach following Kleven et al. (2023) to address this temporal proximity.

We study how getting married and having a first child affect people over time. To do this, we use a newer statistical method that avoids the common mistakes found in older approaches (De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille 2020). This method works well for complicated situations like ours, where people experience these life events at different ages and the effects can change over time. Because marriage and having a first child can happen close together, we estimate the effect of each event while carefully accounting for the other. This lets us trace how outcomes change before and after each event without mixing up their separate impacts. We also run several additional checks to make sure our results are reliable and to understand why we see the patterns we do.

Results

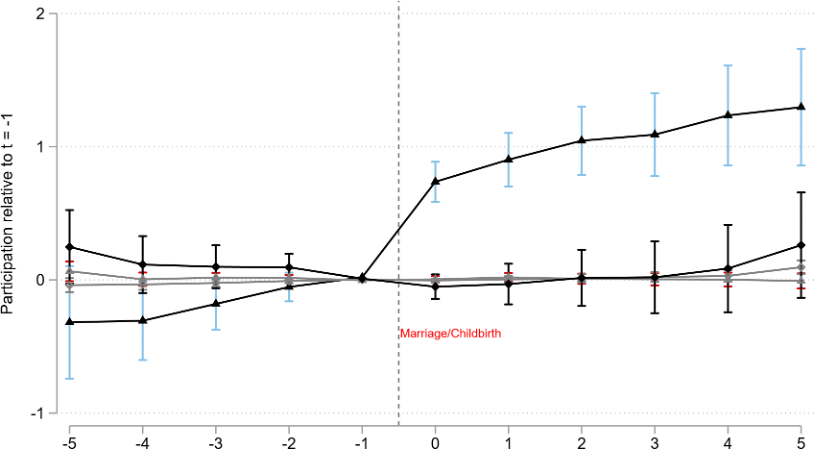

Figure 1 presents a joint event study of marriage and first childbirth for men and women. Two patterns are noteworthy. First, there is a large and sustained “marriage boost” to women’s employment. In the year of marriage, women’s probability of being in the labour force rises by about 74% relative to one year before marriage. Over the first five years after marriage, women’s participation more than doubled compared to the pre-marriage level. However, there is no comparable change for men; their participation is already high and remains stable over the same period.

Figure 1. Impact of marriage and first childbirth on overall workforce participation

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the India Working Survey.

Descriptively, women’s workforce participation in our rural sample rose from 27% in the year before marriage to an average of 49% in the first five years after marriage. This additional participation is largely as contributing family workers or in informal agricultural employment.

Second, there is no statistically significant “child penalty” on women’s employment. In the year of first childbirth, women’s participation falls slightly (by about 5 percentage points), but this decline and subsequent changes in the next four years are not statistically significant. There is no impact on men’s participation rate due to first childbirth.

In other words, marriage – not childbirth – is the transformative event for women’s employment trajectories in this rural context. First childbirth does not push women out of the labour market in the way documented for many high- and middle-income countries.

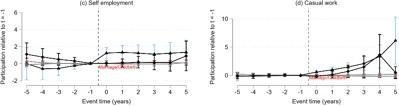

We also pose the question on what kinds of jobs are women engaged in? Figures 2 and 3 present the shift in employment patterns due to marriage and childbirth. We find that both paid work and contributing family work jump after marriage. The largest increase is in informal paid work – self-employment and casual wage employment – mostly in agriculture. Formal, regular salaried employment remains very low for women both before and after marriage and does not change significantly. After childbirth, none of these work categories shows a significant change over a five-year horizon.

Heterogeneity analysis shows that the marriage-related increase in work is larger for women from poorer households, for women whose mothers worked, and for those who married earlier.

Figure 2. Impact of marriage and first childbirth in paid and contributing family work participation

Figure 3. Impact of marriage and first childbirth on type of employment

Why does marriage increase, and childbirth have no impact on women’s work?

These results paint a strikingly different pattern from that seen in high- and middle-income countries that show a significant negative impact on women’s labour force participation and earnings post childbirth. We argue that the increase in women’s employment after marriage, coupled with stagnant formal employment and the absence of a child penalty, reflects the specific social and economic realities of rural India. Several mechanisms likely operate together:

Norms and mobility constraints for unmarried women: Unmarried girls face stricter limits on mobility and work outside the home, tied to ideas of purity and family honour. Marriage relaxes some of these constraints, making it socially more acceptable for women to work, especially in family farms or local casual jobs.

Role-model and intergenerational effects: The larger increase in labour market participation among women whose mothers had been employed suggests an important intergenerational channel – exposure to working mothers may shape daughters’ beliefs about working after marriage and lower psychological or social barriers.

Economic need and informal rural labour markets: After marriage, women are expected to economically contribute to their marital households. Poor rural households rely heavily on all available labour; women’s work therefore is an economic necessity. Informal agricultural and home-based work allows women to combine domestic and income-earning responsibilities, even when childcare is intensive.

These mechanisms also overlap with why we do not observe a sharp “child penalty” in this rural context – norms driving early marriage and childbirth, the dominance of informal and seasonal agricultural work, and limited access to salaried jobs. Most women in our sample marry and have their first child in their late teens or early twenties, long before they could accumulate stable formal work experience. Family farming, self-employment, and casual wage work can be scaled up or down and fitted around care rather than exited entirely; and strong expectations that married women contribute to household production, especially in poorer families, mean that motherhood changes how and when women work more than whether they work.

Taken together, these patterns suggest that continued work after childbirth in our setting is not primarily a marker of greater choice or high-quality opportunities, but of constrained options and necessity-driven participation in low-paying informal jobs.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest that the absence of a child penalty in rural areas does not equate to improved welfare. The employment post marriage is almost entirely in low-productivity informal jobs and is strongest among poorer households. Policy attention needs to go beyond headline participation rates and focus on improving the quality, security, and returns to women’s employment and providing greater access to maternal benefits in such jobs. At the same time, as the economy formalises, there is a window to design gender-sensitive labour regulation, sustainable financing of maternity and parental leave, and employer incentives that can pre-empt the emergence of large child penalties in formal jobs.

Notes:

(i) The figure shows, for women and men separately, the estimated impacts of marriage and childbirth on overall work participation rates (Estimated Equation 2; Rural Women: Observations: 13,616, Unique Individuals: 1,184; Rural Men: Observations: 9,063, Unique Individuals: 711). (ii) The vertical axis is the scaled coefficient Pτ that measures the impact of marriage and childbirth as a percentage of the counterfactual outcome relative to the year before marriage and childbirth, respectively. (iii) Calendar-year and age-in-year fixed effects are controlled in the regression. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. (iv) The same is applicable to Figure 2 and Figure 3 below.

Further Reading

- Berniell, Irini, Laura Berniell, Daniela de la Mata, María Edo and M. Marchionni (2023), “Motherhood and flexible jobs: Evidence from Latin American countries,” World Development, 167: 106225.

- Das, MB and I Žumbytė (2017), ‘The motherhood penalty and female employment in urban India’, Policy Research Working Paper 8004, World Bank.

- De Chaisemartin, Clément and Xavier D'Haultfœuille (2020), “Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects”, American Economic Review, 110(9), 2964-2996. Available here.

- Deshpande, A and J Singh (2021), ‘Dropping out, being pushed out or can’t get in? Decoding declining labour force participation of Indian women’, IZA Discussion Paper, IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

- Juhn, Chinhui and Kristin McCue (2017), “Specialization then and now: Marriage, children, and the gender earnings gap across cohorts”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1): 183-204.

- Lahoti, R, R Abraham and H Swaminathan (2024), ‘Marriage, motherhood, and women’s employment in rural India’, ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 757, Asian Development Bank.

- Kleven, H, C Landais and G Leite-Mariante (2023), ‘The child penalty atlas’, NBER Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Kleven, Henrik, Camille Landais, Johanna Posch, Andreas Steinhauer and Josef Zweimüller (2019), “Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 122-126. Available here.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.svg)

.svg)

.svg)