Can quotas for women in politics induce institutional change in the long run? This column examines whether affirmative action for women in Indian local government had spillovers into state and national offices. It finds that reservations in local government may have been responsible for around half of the increase in female candidacy in parliamentary elections since 1991. However, female representation in higher offices remains low.

Quotas are an increasingly common tool to improve the economic and social participation of historically underrepresented groups in education, business, and politics. India has one of the most expansive and long-standing systems of political quotas in the world, which has provided fertile ground for learning about the short- and long-term effects of political empowerment of women and ethnic minorities. These policies have been the focus of a number of studies to date improving our understanding of the benefits of more diverse political representation on the provision of public goods (Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004), crime and trust in the government (Iyer et al. 2012), and attitudes towards female leaders (Beaman et al. 2009), or girls in general (Kalsi 2015).

Myerson (2012, 2014) suggests that a strong supply of capable local leaders is necessary for effective State-building in a tiered and decentralised governance structure. Often implicit in the advocacy for quotas is an argument that they will increase the representation of targeted groups in a way that can eventually render the policy obsolete through institutional change. Whether such institutional change is possible has long been debated in the many contexts in which quotas or affirmative action policies have been proposed and advocated (Jensenius 2016), and it is an open question as to whether quotas can have broader effects in areas in which they are not directly applied (Bhavnani 2009).

In recent research, I ask: how do quotas for women in local elected bodies in India affect candidacy for, and representation in, higher offices? This investigation ultimately asks whether quotas intended to increase the inclusive nature of local political institutions can change the prospects for candidacy by, and representation of, beneficiary groups in higher offices. I empirically test whether such a quota system can increase participation and representation in higher levels of government, and if so, through which channels (O’Connell 2017).

Context

India first introduced nationwide seat quotas for women in government in 1993 with the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Indian Constitution. The 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act instituted a three-tiered system of local government in rural areas consisting of the village, sub-district (block), and district levels across rural areas of the country. The Amendments, which were intended to provide large-scale devolution and decentralisation of powers to the local bodies, stipulated that members of the local governance bodies were to be elected at five-year intervals, and provided for one-third of all seats at each governance level to be filled by women.

Methodology

Once the provisions of the reform were implemented, one-third of seats were reserved for women at any level of the local governance hierarchy; for single-seat leadership positions, reservations were assigned randomly across areas in each election cycle such that in aggregate, the one-third quota would be met. This feature of rotating leadership assignment has been used to assess the effects of women leaders in previous studies, including Iyer et al. (2012) and Beaman et al. (2012). After several election cycles there is considerable variation across areas in the cumulative number of years exposed to a woman in the leadership position. It is this variation in cumulative exposure to quotas applied to district leadership seats – at the highest level of this governance structure – that provides exogenous (external) cross-sectional (at a given point in time) variation in exposure to women leaders used to identify dynamic effects across levels in the political hierarchy.

I use the rotating assignment mechanism of district chairperson seats to identify effects of cumulative exposure to local female leadership on candidacy for state assembly elections from 2004 to 2007 and the parliamentary election in 2009. By the late 2000s, some districts had seen the chairperson seat reserved for three election cycles, while others had only just seen their first cycle of reservation or had not yet been reserved at all. This variation is used to identify the effects of local female political leadership on candidacy for, and representation in, higher offices.

Results

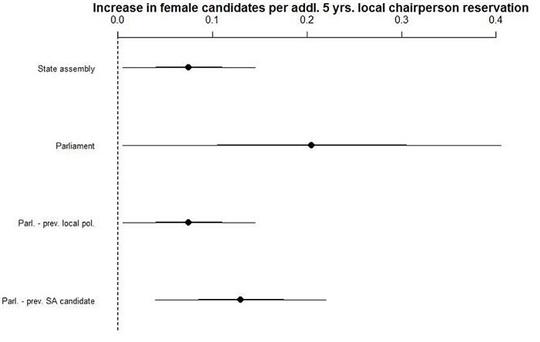

The quota policy in local government increases later female candidacy in both state and national legislature elections. An additional election cycle (five years) of quotas increases the number of female candidates for state assembly elections by .075 candidates. In the parliament, this candidacy effect is larger, with an average of 0.25 additional female candidates per reserved cycle. This implies an additional female candidate would appear among four constituencies that had seen one additional reserved local term. It is important to note that there are nine to 10 assembly constituencies per district, on average; per district, the effect on aggregate state assembly candidacy is then between one and two additional female candidates for an additional two election cycles of exposure. That the effect is stronger at the state legislature level when comparing similar areas also suggests that the state legislature may be seen as a logical intermediate career step for politicians from previously reserved areas. This effect magnitude also very closely mirrors the number of district chairpersons that would have been available for higher office: two cycles yield between one and two new politicians created by the chairperson quota. There are mixed results as to whether quotas in local government can increase the representation of women in higher offices. The new female candidates that appear after quota exposure do not win the elections they contest, and the majority run as independents – lacking access to the resources and support of established political parties. New female candidates win a roughly proportional share of votes, and there is limited evidence of changes in voter turnout.

Figure 1. Effect of additional five years of quotas on later female candidacy in elections

Note: Figure presents main coefficient estimates and 95% confidence interval of the effect of additional years of exposure to local female leaders on female candidacy in state and national legislature elections. Coefficients scaled by five to present effect magnitudes per additional term.

Note: Figure presents main coefficient estimates and 95% confidence interval of the effect of additional years of exposure to local female leaders on female candidacy in state and national legislature elections. Coefficients scaled by five to present effect magnitudes per additional term. A remaining question is whether the increase in candidacy is a result of the creation of politicians in local government who contest for higher office, or is a response of potential candidates to run in areas where female leaders are more likely to be seen as capable. I find that approximately half of the candidacy effect is due to the supply channel (that is, ‘contesting up’), while the other half was due to repeat candidates contesting in longer-exposed constituencies. This suggests that both the supply and demand channels may be at work in increasing female candidacy for higher office.

Conclusion

The quota policy for women in local government increases candidacy for, but not representation in, state and national political offices. This suggests additional, longer-term effects of quotas on political dynamics and effects outside the particular level of government in which the quotas were active. Estimate magnitudes imply these quotas were responsible for a majority of the increase in female candidates in state legislature and parliamentary elections since the policy went into effect, although female representation in higher offices remains low and does not appear to be changed by the policy. In sum, it remains to be seen whether quotas in local government can generate an increase in representation by women in higher levels of government.

Further Reading

- Beaman, Lori, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande and Petia Topalova (2012), “Female Leadership Raises Aspirations and Educational Attainment for Girls: A Policy Experiment in India", Science, 335(6068):582-586. Available here.

- Beaman, Lori, Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande and Petia Topalova (2009), “Powerful women: Does exposure reduce bias?", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4):1497-1541. Available here.

- Bhavnani, Rikhil R (2009), “Do Electoral Quotas Work After They Are Withdrawn? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in India", American Political Science Review, 103(1):23-35. Available here.

- Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra and Esther Duflo (2004), “Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India", Econometrica, 72(5):1409-1443. Available here.

- Finan, F, BA Olken and R Pande (2015), ‘The Personnel Economics of the State’, in Handbook of Field Experiments, forthcoming. Available here.

- Iyer, Lakshmi, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra and Petia Topalova (2012), “The Power of Political Voice: Women's Political Representation and Crime in India", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(4):165-93. Available here.

- Jensenius, FR (2016), Social Justice through Inclusion: The Consequences of Electoral Quotas in India, Oxford University Press, 31 July 2017.

- Kalsi, Priti (2017), “Seeing is Believing: Can Increasing the Number of Female Leaders Reduce Sex Selection in India?", Journal of Development Economics, 126:1–18. Available here.

- Myerson, RB (2012), “Standards for State-Building Interventions," Mimeo.

- Myerson, RB (2014), ‘Local and National Democracy in Political Reconstruction’, mimeo.

- O’Connell, SD (2016), ‘Can quotas increase the supply of candidates for higher-level positions? Evidence from local government in India’, mimeo, October. Available here.

28 August, 2017

28 August, 2017

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.