The Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill 2019 seeks to provide for the advancement of “economically weaker sections”, through 10% reservation in government jobs and higher educational institutions – a shift in focus from caste as basis of quotas. This article analyses the caste profile of those classified as poor, and highlights that caste-based inequalities continue to exist in several economic indicators.

The Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill 2019, popularly known as the 10% quota for the economically weaker sections (EWS), is a landmark in the history of India’s reservation policy – not because it advances the original raison d’etre underlying quotas for marginalised and stigmatised groups, but because it completely turns the original logic of reservations on its head.

Reservation for the most oppressed groups was conceptualised as a policy of ‘compensatory discrimination’ – a remedial measure for contemporary handicaps faced by individuals due to historical discrimination and deep stigmatisation on account of their ‘untouchable’ caste status.

Quotas on an economic basis, with a specific rider that these are meant for EWS among the non-SC/ST (scheduled caste/tribe), indicate two shifts in the policy of affirmative action: one, that caste is not necessarily an indicator of social backwardness; and two, that reservations are not meant specifically to remedy past and current caste-based discrimination. Additionally, while the new quota is ostensibly meant for EWS, in reality the government has set an income limit of Rs. 800,000 per annum, below which households are classified as EWS. How valid are these shifts in government policy? Does the income ceiling proposed by the government reflect actual economic disadvantage?

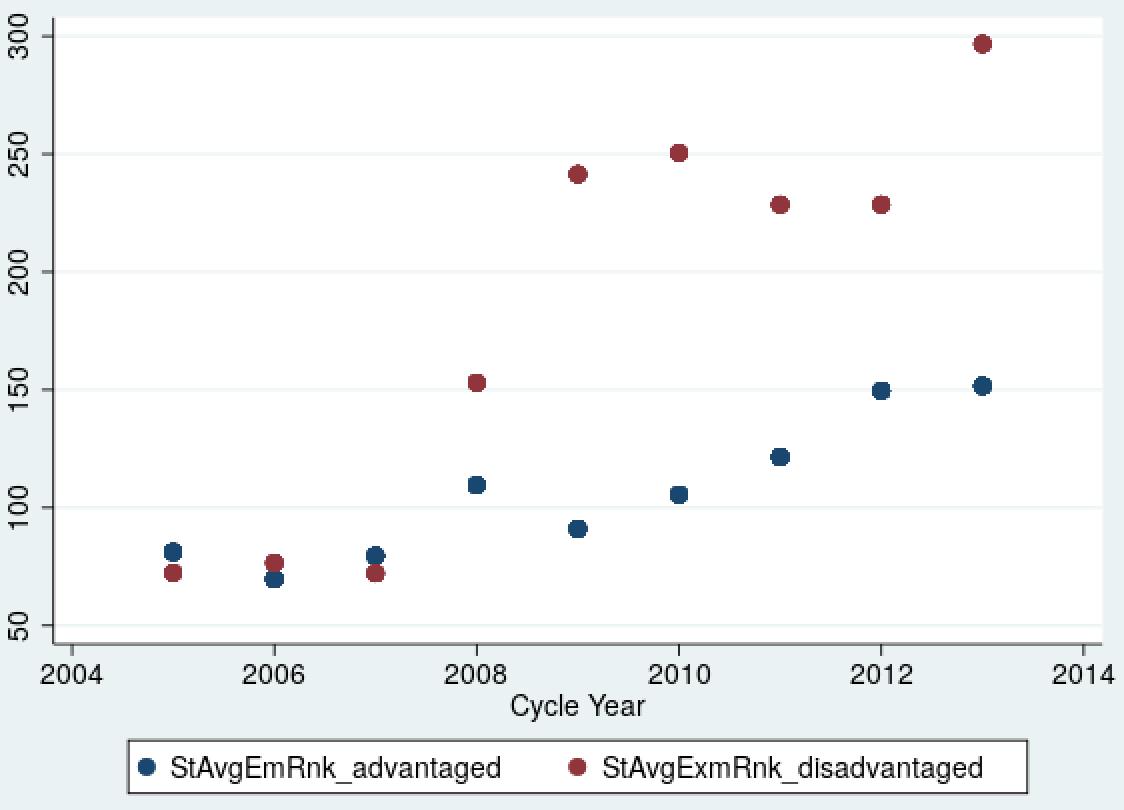

We address these questions using data from two waves of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS). We first examine the evidence on caste disparities within those officially classified as poor (that is, below poverty line, or BPL), and how these have changed between 2005 and 2012. Even though the poverty line is not the cut-off for EWS, this evidence is necessary in order to address the first question: has caste ceased to be an indicator of backwardness? In Deshpande and Ramachandran (2019), we provide the latest evidence on the overall salience of caste in economic indicators such as education, employment, wages etc, and demonstrate that in several indicators, caste gaps are either static or widening. Given that the new quota targets the so-called EWS without reference to a specific caste group, it raises the question about whether caste differences are significant among the poor.

Does caste still matter among the poor?

Let us first focus on those officially classified as poor (BPL) according to the Tendulkar Committee poverty line. Columns 1-3 and 5-7 of Table 1 present selected indicators for poor Brahmins1, poor UCs (non-Brahmin upper castes) and poor SCs (Dalits) for 2005 and 2012 respectively.

Income and wealth

In 2005, the average annual household income of poor SCs was roughly 76% of the average income of poor Brahmins, and about 56% of the poor UCs. In 2012, it was 73% the income of poor Brahmins, and almost 73% of the income of the poor UCs. Thus, in both years, poor Dalits earn significantly less than poor Brahmins and poor UCs. Over the seven-year period, we see some convergence between Dalit incomes and Brahmin and UC incomes among the poor, but notice that the convergence between Brahmin and UC incomes is much sharper. In 2005, the absolute gap between poor Brahmin and poor Dalit incomes was roughly 31% of poor Dalit incomes. In 2012, the same gap was roughly 36% of poor Dalit incomes.

The disparities in terms of land ownership or cultivation are even more stark: of all those who report being involved in agriculture, 59% of poor Brahmins owned or cultivated land in 2005, and this figure increased to 91% by 2012. For poor UCs, the increase was from 39% to 75%, which was substantial but smaller than that for Brahmins. The smallest increase was for poor Dalits (from 35% to 48%).

This evidence suggests that poor Dalits are clearly worse-off than poor Brahmins and poor UCs in terms of income and wealth. The IHDS in 2012 asked a question about self-perceptions of economic status: “According to you, is your household poor, middle-class or comfortable?” Analysing the caste differences in the responses to this question among the poor is revealing: only 40% of poor Brahmins view themselves as poor, compared to 77% of poor Dalits, and 57% of all Dalits. This self-perception is shaped by the relative social status, which for poor Brahmins remains high, despite their objective economic disadvantage, and for non-poor Dalits, remains low, even when they are not below the poverty line. The same pattern is seen for the middle-class and comfortable categories as well.

Table 1. The poor across caste groups; 2005 and 2012, All-India

Education

We see that in 2005, the average number of years of education for adults in poor Brahmin families was the highest at 3.46, followed by poor UCs at 3.22, poor Dalits at 2.36, and all Dalits with 3.15 years of education. By 2012, average education increased for all groups, but whereas poor Brahmins and poor UCs added about two years to stand at 5.55 and 4.21 respectively, poor Dalits increased their average to only 3.61 over the seven-year interval. Number of years of education of the highest educated adult shows similar caste gaps, where poor Brahmins have more years of education not only relative to poor Dalits, but to all Dalits.

Since the discussion is about quotas in government jobs and institutes of higher education, it is instructive to examine the relative eligibility of these groups for these positions. Examining the proportions of poor families with at least one member with 12 years or more education2 shows that in 2005, 22.81% of poor Brahmin households had at least one member with 12 years or more of education, and this proportion was zero for poor UCs and SCs. In 2012, the proportion of households with at least one member eligible to take advantage of quotas increased to 39.37% for poor Brahmins, 16.48% for poor UCs and 11.71% for poor SCs. Thus, based on educational attainment, poor Brahmins are the best suited to take advantage of the new quotas.

Employment

Differences in access to jobs can be analysed in a variety of different ways; a reality check tells us that casual labour characterises the nature of employment for the overwhelming majority of the poor. The proportion of poor individuals with casual jobs (of all working individuals) declined for all caste groups between 2005 and 2012, but the decline was the highest for Brahmins: 14 percentage points for Brahmins from 85 to 71, whereas the proportion of UCs and Dalits with casual jobs declined by seven (96 to 89) and five (from 97 to 92) percentage points respectively. The proportion of casual workers is higher among all Dalits compared to poor Brahmins.

For the poor of all castes, a formal sector government job remains a distant dream, with 1% of poor Brahmins and Dalits in government jobs. The fact that despite significant gaps in other material indicators, the percentage of poor Brahmins and Dalits in government jobs is similar is probably due to existing reservations for SCs.

Comparison with all SCs

Columns 4 and 8 show the values of all indicators for all SCs, not only the poor, for 2005 and 2012 respectively. The relative position of caste groups becomes even clearer here, in that we see that all Dalits are either at par or barely above poor Brahmins. The historical legacy of excluding Dalits from all education can be seen in terms of years of education, where average years of education of all Dalits is lower than that for poor Brahmins in both years. The proportion of all Dalits with casual jobs is higher than that for poor Brahmins in both years.

Rs. 800,000 per annum: Economically weaker section?

The comparison so far has been based on BPL families, or those officially classified as “poor”. For all those who argue that economic disadvantage is the true marker of deprivation and that caste is not relevant any more, the comparison presented above should be a reality check.

For the purpose of this quota, the EWS category comprises households with an annual income less than Rs. 800,000. 98.26%, 97.93%, and 99.75% of Brahmin, UC, and SC families in the IHDS, respectively, report income less than the EWS limit.

Income data at the national level are not easily available. Another estimate3 indicates that in 2015, 98% of all households earned an annual income of Rs. 600,000 or less. It is worthwhile to remind ourselves that income cut-off for identifying children from EWS families for admission into elite private schools in Delhi is annual parental income of less than Rs. 100,000. Thus it is completely false to characterise this as a quota meant for EWS.

By stipulating a quota for non-SC/ST and non-OBC (other backward classes) families earning Rs. 800,000 or less, the government is effectively creating a quota exclusively for Hindu UCs, who are not in the top 1% of the income distribution. This means that despite being presented as quota on economic criteria and not caste, the reality is that this is very much a caste-based quota, targeted towards castes that do not suffer any social discrimination; on the contrary, these are the highest ranking in social scale of ritual purity.

By questioning the validity of the 10% quota, we are not at all suggesting that protective, inclusive, or remedial measures targeted towards the (actual) poor should not be considered. We firmly believe in public policies that promote diversity along several dimensions, including class, caste, religion, gender, and other social markers.

Besides, the income ceiling for the 10% quota makes it clear that it is not really targeting the poor, but reserving a slice of a shrinking pie for UCs, to provide an illusion that it is doing something towards ensuring decent jobs. If the government wants to tackle poverty, it needs to strengthen anti-poverty programmes, in addition to making the nature of the growth process more inclusive. Public education and health systems remain in dire conditions as manifested in low levels of learning and high levels of malnutrition. There is a strong need for investment in social infrastructure, and policy that is geared towards equalising early-life opportunities to provide a platform for equitable growth.

Notes:

- Brahmins are members of the highest caste in Hinduism.

- This is based on the assumption that individuals need at least secondary education to access a low-level government job, and 12 years of schooling to enter college.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/653897/average-monthly-household-income-india/; accessed 3 March 2019.

Further Reading

- Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2019), “Traditional Hierarchies and Affirmative Action in a Globalising Economy: Evidence from India”, World Development, (118), 2019: 63-78.

- Deshpande, Ashwini and Rajesh Ramachandran (2019), “The 10% Quota: Is Caste Still An Indicator of Backwardness", Economic and Political Weekly, LIV(13), 30 March 2019.

17 May, 2019

17 May, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.