How prepared is India for inflation targeting? This column suggests that the larger weight assigned by the RBI to tackling inflation over the years, relative to other policy objectives such as stabilising exchange rates, places it in a good position to make the transition to the new regime. However, limited control over supply shocks that impact inflation might continue to pose a challenge. Greater coordination between fiscal and monetary policy would improve the efficacy of inflation targeting.

Early last year the Expert Committee to ‘Revise and Strengthen Monetary Policy Framework’ made several important recommendations related to the conduct of monetary policy in India. In particular, the Committee recommended that monetary policy should target the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation, and move towards an inflation-targeting regime over the next two years with a target of 4% inflation (with a band of ±2% around it).1 In February 2015, the government and Reserve Bank of India (RBI) operationalised the framework by agreeing that monetary policy’s primary objective would be to maintain price stability, while keeping in mind the objective of growth. It was also agreed to bring inflation down to 6% by January 2016, and then strive to keep it within a ±2% band of the central target of 4%.

Inflation targeting has been a subject of a long-standing debate, especially in the Indian context. The supporters have advocated a move towards inflation targeting owing to the associated benefits including low and stable inflation, adherence to a well-defined rule as opposed to a discretionary approach of conducting monetary policy, and the related benefits of transparency and accountability. On the other hand, opponents of inflation targeting have pointed out the impracticality of the regime due to vulnerability of inflation to supply shocks, such as those arising from an adverse monsoon or a rise in the cost of global crude oil, that are outside the ambit of the monetary policy. Furthermore, weak transmission channel through which monetary-policy decisions affect the economy in general and the price level in particular, due to the presence of administered prices and illiquid bond markets, is also an impediment.2 In a recent paper, we examine the extent to which the current macroeconomic environment in India is indeed suitable for the implementation of inflation-targeting (Sen Gupta and Sengupta 2014).

Managing the policy trade-offs

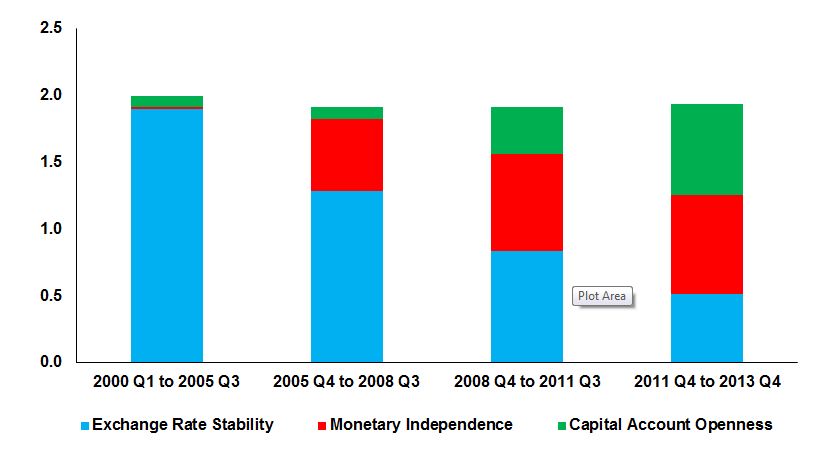

A move towards an inflation-targeting regime would entail the RBI managing the “Impossible Trinity” or “Trilemma”, which points out that it is impossible for a central bank to set interest rates autonomously in response to domestic macroeconomic requirements without being influenced by global interest rates (monetary policy independence), and also maintain a fixed exchange rate with a major currency or currency basket (exchange rate stability), as well as have integration with global capital markets (capital-account openness), simultaneously. Only two of the three objectives can be fully attained at a particular point in time. Given India’s continuous and enhanced integration with global capital markets, the recent transition to an inflation-targeting regime, and the implied necessity of being able to independently adjust the domestic monetary policy, it would be difficult for the RBI to actively intervene in foreign exchange markets in a sustained manner so as to stabilise the exchange rate in the face of global economic shocks.

Figure 1. Policy trade-offs under the “Impossible Trinity”

Source: Sen Gupta and Sengupta (2014)

Source: Sen Gupta and Sengupta (2014)

Analysing the movement of domestic interest rates vis-à-vis global rates, co-movement of the rupee with major currencies as well as the extent of capital flows over the 2000-2013 period, we conclude that over time there has been a steady decline in the priority accorded to having a stable exchange rate, especially between 2009 and 2012. The rupee appreciated against the US dollar by nearly 17% between March 2009 and April 2010. Similarly, between August 2011 and December 2011, the rupee depreciated by 19% on the back of a widening current account deficit and weak capital inflows. The rupee witnessed heightened volatility in 2013 as well. A high current account deficit and signals of tapering of the quantitative easing by the US Federal Reserve resulted in the rupee depreciating by 21% between May and August 2013.

In contrast there has been a steady increase in the priority accorded to both capital account openness and monetary independence in context of the ‘Trilemma’. The rise in capital-account openness has been driven by India’s gradual but steadily increasing integration with global capital markets. While the sum of capital inflows and outflows as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased from 21% in 2000 to 52.1% in 2013, the excess of capital inflows over outflows witnessed an increase from 1.9% to 2.6%. At the same time, the RBI pursued a more independent monetary policy. After the initial softening of monetary policy to stimulate growth in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, the RBI began tightening monetary policy from March 2010, in response to high and persistent domestic inflation. This was in contrast with the advanced economies, which were continuing to follow a soft monetary policy to stimulate growth.

The increased emphasis on monetary independence along with a reduced focus on stabilising the exchange rate makes RBI well placed to transition towards an inflation-targeting regime. Focusing on price stability would imply RBI would have to maintain this trend and relinquish its control over exchange rate movement. Thus, the benefits of lower inflation need to be balanced with the economic costs associated with exchange rate volatility.

Assessing RBI’s preferences

Having corroborated a shift towards greater monetary autonomy in setting the interest rates, the next issue relates to choice of an appropriate target. Under inflation targeting, the central bank focuses on an explicit nominal target - the CPI inflation rate. Hence, it is important to understand historically the relative weights placed by RBI on varying policy objectives.3 Mohan (2006) has argued that in the past, the multiple goals of the RBI resulted in a flexible and time-variant approach towards monetary policy with a continuous rebalancing of priority between growth and price stability. American economist John Taylor in 1993 formulated a methodology to evaluate the extent to which US Federal Reserve adjusts the policy rate in response to past inflation and the output gap (actual less potential output).4 We use this methodology to gain insights into the “revealed preferences” of the RBI since the 1990s.5

Overall we find that inflation matters more than output if we are to use the Taylor Rule to understand Indian monetary policy. There has been greater sensitivity to wholesale price index (WPI) inflation in recent times compared to CPI, whereas exchange-rate changes do not seem to play a crucial role . The greater emphasis on inflation bodes well for the shift towards inflation targeting but going forward the nominal anchor has to shift from WPI inflation to CPI inflation.

Which inflation to target?

The new monetary policy framework clearly establishes CPI inflation as the nominal anchor, which is the final goal of monetary policy. We assess the suitability of using CPI inflation as the anchor by identifying the main drivers of aggregate CPI inflation, and distinguish between the roles played by demand- and supply-side drivers. We find that a 1% increase in agricultural output is associated with a 0.39% decline in prices, while a 1% rupee depreciation results in 0.4% rise in aggregate prices. Fuel prices have a significant effect on overall inflation as well with a 1% rise in fuel prices being associated with a 0.68% rise in aggregate prices. Thus supply-side factors such as agricultural output and fuel prices, as well as exchange rate, which are traditionally outside the control of monetary policy, exert a strong impact on aggregate prices in India. This could impact the efficacy of the inflation-targeting regime.

These findings raise concerns about the efficacy of using CPI inflation as the nominal anchor given that CPI inflation is highly sensitive to supply-side pressures, and monetary policy has limited bearing on these supply-side drivers.

Supportive fiscal policy

Fiscal dominance, or the extent to which government deficits condition the growth of the money supply, plays an important role in determining the success of an inflation-targeting regime. The government can choose to finance the deficit by issuing bonds, which can raise the aggregate money supply in the economy.

India’s experience with fiscal rules has been rather mixed. While the fiscal deficit has declined over the period 2001-02 to 2007-08, and is once again on a downward trend since 2011-12, India has often breached the targets set by various Finance Commissions and other Committees over the last decade. The postponement in the recently concluded Union budget of achieving 3.0% fiscal deficit by a year to 2017-18 continues this practice.

We find from our analysis that fiscal shocks have an important bearing on inflation. These shocks lead to a jump in inflation rate, which takes more than two years to subside. Moreover, these shocks to fiscal deficit are important in explaining the volatility of inflation. We find that these shocks explain about 18% of the variation in inflation after three quarters. Hence, any success of the monetary policy in containing inflation would be crucially contingent on an appropriate fiscal policy.

Concluding remarks

We conclude that historically larger emphasis by the RBI on dealing with inflation, along with the RBI gaining greater monetary independence and allowing exchange rate flexibility, places it in a good position to make the transition to the new regime of inflation targeting. However, it might be crucial to recognise in this context that some of the major drivers of inflation are outside the control of monetary policy and also that a supportive fiscal policy would be vital to the success of the new inflation-targeting regime.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.

Notes:

- In India, inflation is mainly measured using the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) and Consumer Price Index (CPI). While WPI is based on price of goods at a wholesale stage (goods that are sold in bulk and traded between organisations instead of consumers), CPI is based on price of goods and services faced by the consumer.

- In India, administered prices (such as Minimum Support Prices (MSPs)) constitute an integral component of overall price indices, and impact inflation. Thus, an inflation-targeting policy, in order to be effective, needs to incorporate the timing and magnitude of changes in these prices. Furthermore, illiquid financial markets impede the transmission of the impact of a change in the policy rate to consumption or investment behaviour, thereby reducing the efficacy of an inflation-targeting regime

- These objectives have varied from maintaining price stability, sustaining growth momentum, ensuring financial stability, and minimising exchange rate volatility.

- In Taylor (1993), the policy rate refers to the Federal funds rate in the US, which is the rate at which depository institutions actively trade balance with the Federal Reserve.

- Revealed preference, a term borrowed from consumer demand theory, here implies that if two policy choices a and b are available, and if it is observed that a is chosen over b, then a is said to be revealed preferred to b.

Further Reading

- Blanchard, O (2004), ‘Fiscal Dominance and Inflation Targeting: Lessons from Brazil’, NBER Working Papers 10389, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hutchison, Michael M, Rajeswari Sengupta and Nirvikar Singh (2010), “Estimating a Monetary Policy Rule for India”, Economic & Political Weekly, September 18, 2010, Vol. XLV, No. 38.

- Hutchison, Michael M, Rajeswari Sengupta and Nirvikar Singh (2013), ‘Dove or Hawk? Characterizing Monetary Policy Regime Switches in India’, Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 16c, pp 183-202.

- Mohan, R (2006) ‘Monetary policy and exchange rate frameworks-the Indian experience’, Presentation at the Second High Level Seminar on Asian Financial Integration organised by the International Monetary Fund and Monetary Authority of Singapore, Singapore.

- Sen Gupta, A and R Sengupta (2014), ‘Is India Ready for Flexible Inflation Targeting?’, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, WP 2014-19.

- Taylor, JB (1993), “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39:195-214.

16 March, 2015

16 March, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.