The development paths of India and Brazil are, in some ways, mirror images of one another. While growth and inequality were both high in Brazil until 1980 and then declined – first growth declined in the 1980s, and later inequality – the reverse is true for India. This column compares the experiences of the two countries, examining their patterns of growth and inequality and the factors that underpin them.

Inequality is a global issue, but one that is receiving particular attention in India and Brazil. In the 1970s and 1980s, Brazil reported one of the highest levels of income inequality in the world. On the other hand, India, despite its embedded inequalities due to caste and the colonial legacy, seemed to share its poverty more evenly. Views of inequality and development were greatly influenced by the work of Simon Kuznets, who suggested that growing inequality was likely in the early stages of industrialisation and urbanisation, but that once a certain level of development had been reached, inequality would start to decline. However, the experience of India and Brazil does not support the idea that there are general laws. Inequality is bound up with the nature of the growth path and the economic and social institutions that underpin it. Although both economies opened up to global markets in the 1990s, different growth regimes were established, accompanied by improving income distribution in Brazil and worsening in India. A comparison of the two countries, despite their very different histories and social and economic structures, or perhaps precisely because of these differences, can help to understand the mechanisms involved.

Growth and inequality in India and Brazil

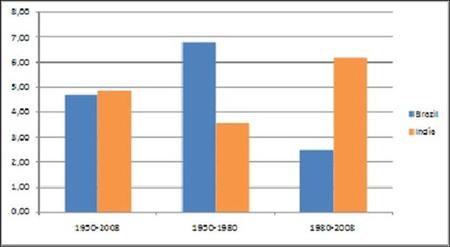

In some important ways, the development experiences of Brazil and India are mirror images of each other. Since the middle of the twentieth century, both countries have had a similar average rate of growth of between 4% and 5% per year. But Brazil grew rapidly up to 1980 while India grew slowly; and then after 1980 the pattern was reversed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual GDP growth in Brazil and India, 1950-2008

Source: Maddison database; Statistics on World Population, GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD (1990 International Dollars).

Source: Maddison database; Statistics on World Population, GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD (1990 International Dollars).

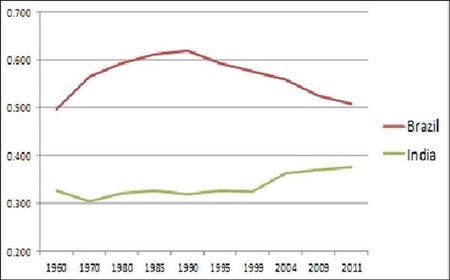

The mirror image can also be seen in the long-term trend of inequality. Income inequality in Brazil rose rapidly until the 1980s, but then started to decline in the 1990s and more steeply after the turn of the century. Inequality in India showed little change until the 1990s, but then started to rise (Figure 2). The reasons for these differences lie more in the nature of growth than in its pace. To explain them we need to understand the ‘growth regime’ in each country as a whole, including economic structures, labour market institutions, agrarian systems, the functioning of markets, the pattern of international integration, monetary and fiscal relations, and the role of the State.

Figure 2. Inequality of income (Brazil) and expenditure (India), 1960-2011

Sources: India – National Sample Survey (NSS), various years; UN-WIDER World Income Inequality Database for earlier years. Brazil - Prepared by authors based on PNAD/F.IBGE data.

Sources: India – National Sample Survey (NSS), various years; UN-WIDER World Income Inequality Database for earlier years. Brazil - Prepared by authors based on PNAD/F.IBGE data.Notes: These are Gini coefficients of household income per capita (Brazil) and household expenditure per capita (India). The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality that lies between 0 (complete equality) and 1 (all income received by one person). Long series of income data are not available for India, but income inequality is usually greater than expenditure inequality, and in 2011 there was probably not much difference between the two countries in income inequality.

Understanding the patterns of growth and inequality

Historical context

To understand inequality today it is necessary to examine the historical pattern of growth. Both India and Brazil embarked on a state-led development process in the mid-twentieth century, though with different forms and different results. Up to 1980, Brazil had a successful period of import substitution-led industrialisation, promoted by both democratic and military regimes. Growing inequality reflected differentiation among workers, with the creation of an industrial working class, but also an impoverished informal workforce, non-competitive production structures subsidised by the State, and the growth of a well-off middle class. These structures then persisted through the economic crisis of the 1980s and changed only slowly during periods of stabilisation and liberalisation in the 1990s. Inequality fell more rapidly after 2002 as a result of stronger redistributive policies and the positive performance of the labour market, with increased formalisation and rising wages.

In India, a comparable process of heavy industrialisation in the early years after Independence ground to a halt after the 1960s, and while inequality did not increase there was little reduction in poverty during a period when overall growth was low. As in Brazil, the 1980s were a turning point. A shift to first internal and then, in the 1990s, external liberalisation generated higher rates of growth, reaching over 8% for several years in the decade of the 2000s. While there was a positive impact on wages, formal employment creation was limited and wage differentials grew. The impacts on inequality can be seen in Figure 2. Large income differences between social groups and regions also persisted.

Economic structure

The two countries have very different economies. To start with, per capita GDP (in purchasing power terms) in Brazil is almost three times that in India. Brazil is highly urbanised; over 80% of the population is urban compared to 30% in India. Half of India’s workers are still employed in agriculture, against only 13% in Brazil. Both economies have large service sectors, but India’s has been growing faster than Brazil’s and the Indian economy is widely described as service-led – Indian manufacturing has hardly grown as a proportion of GDP in the last half century. Brazil had a much larger industrial base than India in 1980, but its share in GDP has been declining, and is now similar to India’s at just over a quarter. Both countries have large informal economies, but while India’s dominates the labour market, since half of workers are self-employed and only 7% are in regular formal wage employment, in Brazil only a quarter of workers are self-employed and 45% are in registered wage work. On the other hand, open unemployment is higher in Brazil than in India where underemployed workers are mainly absorbed in informal work.

Despite these differences, many similar issues arise in the two countries. The impact of globalisation, discrimination and segmentation in labour markets, the quality of jobs created, persistent social exclusion, regional imbalances, poorly specified regulation and endemic corruption, insufficient investment in social infrastructure, huge disparities in productivity and many other key determinants of inequality are found in both countries, even if they manifest themselves in different ways.

Labour markets and income distribution

Labour market segregations and segmentations play an important role in inequality in both countries. This is partly a question of the difference in income between formal and informal employment, but there are also large variations in wages, employment security, protection and vulnerability in both formal and informal work. Labour markets are segmented by sex, caste, race and other dividing lines, which gives rise to complex patterns of inequality and exclusion.

There have been recent reductions in income differences in Brazil between formal (registered) workers on the one hand, and informal workers and the self-employed on the other. What is more, the growth of formal employment has been high, in sharp contrast with India, where there has been concern about jobless growth. In India wage differences between casual and regular workers widened in the wake of liberalisation in the early 1990s, though the trend has been reversed in recent years.

Real wages have been rising in both countries. In India there has been a sustained rise since the 1980s for all categories of wage workers, though profits rose faster and the share of wages in national income fell. So rising wages coincided with rising inequality. In Brazil, real labour income rose fast after 2003, and the wage share also rose, so in this period rising wages were associated with falling inequality. But previously real wages had fallen, so wages in 2012 were not much higher than in the mid-1990s or the late 1970s. Clearly there is no simple relationship between wage trends and inequality.

Liberalisation and deregulation clearly contributed to the growth of labour market inequality in India, but this was much less evident in Brazil. A part of the difference lies in stronger institutions for the representation of workers and social protection in Brazil, which were reinforced after 2002. Also, in Brazil, the internal market was the main driver of growth. However, in neither country have trade unions effectively represented the interests of informal workers.

There are several other important contrasts between the two countries:

- The gaps between white-collar occupations on the one hand, and casual or production workers on the other have continued to widen in India. In Brazil, the opposite has occurred due to the rapid increase in the minimum wage.

- Regional inequality in wages and employment is large in both countries, but there is a clear difference in the trends; while this has widened in India in the last two decades, it has narrowed in Brazil.

- Recent reductions in labour market inequality in Brazil are quite broad-based, whether we look at differences by region, sex, or race (colour). The picture in India is much more mixed; some differentials have reduced, while others have persisted or increased. For instance, caste differentials in wages have not declined significantly in recent decades, in contrast to a fall in wage differences by race in Brazil. However, gender wage differentials have declined in both countries.

- With respect to gender equality, though Brazil has moved faster in terms of fertility reduction, urban job opportunities and education, women workers in both Brazil and India continue to face similar challenges - how to reconcile work and family responsibilities, labour market segmentation, and social norms. A disproportionate number of women workers are found in precarious and low-quality employment in both countries.

- In Brazil, the changes in government in recent decades have been accompanied by more substantial changes in social policy than in India, where policies have been more evolutionary (despite political rhetoric to the contrary). Brazil has progressed towards a near universal social safety net (especially through non-contributory pensions and cash transfer mechanisms). In India, social policies have been more targeted and less efficient, while conventional social security has largely been limited to the formal sector.

- Minimum wage regulation in Brazil worked as an engine of inequality reduction because it sets an effective national floor for the income of unskilled workers. Minimum wages in India do not play the same role because they are complex, varying from region to region and from one category to another, and subject to widespread violation and non-compliance.

In both India and Brazil the global economic crisis led to a fall in growth rates in 2008-09, decelerating further since 2011 after a brief recovery. The recessions of the early 1980s ultimately led to shifts in the growth regime in both countries, with opposite effects on inequality. It is too early to tell whether today’s economic crisis will also lead to new institutional configurations. In both countries there are diverse and often competing economic interests, between labour and capital of course, but also among different categories of workers and social groups. New class structures are emerging, as well as new connections between domestic and international capital. The credibility and effectiveness of state regulation of the market is questioned in some quarters. Whether Brazil’s recent experience of declining inequality will be sustained, and whether India’s experience of increasing inequality can be reversed, depends on how the struggles and contradictions between these different forces and trends are resolved in each country.

This column reports some results from a project on Labour Market Inequality in Brazil and India, undertaken by the Institute for Human Development, Delhi (IHD) and the Brazilian Centre for Analysis and Planning, São Paulo (CEPBRAP), and funded by International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada. The column draws on contributions by the project teams in both institutions: Nandita Gupta, Taniya Chakrabarty, Vidhya Soundararajan and Janine Rodgers at IHD, and Professor Maria Cristina Cacciamali, Fabio Tatei, Ian Prates, Eduardo Cury and Magda Chang at CEBRAP. For more information on the project visit www.ihdindia.org/lmi/

29 June, 2015

29 June, 2015

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.