In the sixth and final post of the e-Symposium on ‘Carrying forward the promise of International Year of Millets’, Banerjee and Kundu discuss the extent to which policies implemented as a part of the Odisha Millets Mission improved the production, processing and procurement of the crop. Building on previous work by the Bharat Rural Livelihoods Foundation, they also look at how the Mission was impacted by Covid-19 and other challenges including poor awareness and public perception. They highlight how Odisha's efforts, preceded the International Year of Millets 2023, and how its success can become a model for other Indian states to follow.

Special Programme for Promotion of Millets in Tribal Areas, or Odisha Millets Mission (OMM) started in 2017 to address nutritional security in Odisha through increased millet production and consumption, especially for the indigenous (and often vulnerable) communities. Other important objectives of the mission were to promote machinery for post-harvest processing, improve the productivity of millets, include millets in the Public Distribution System (PDS), Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and other large-scale government programmes, facilitate the export of millets and millet-based products from Odisha, and facilitate Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and self-help groups (SHGs) through government departments geared towards technical product and process innovations.

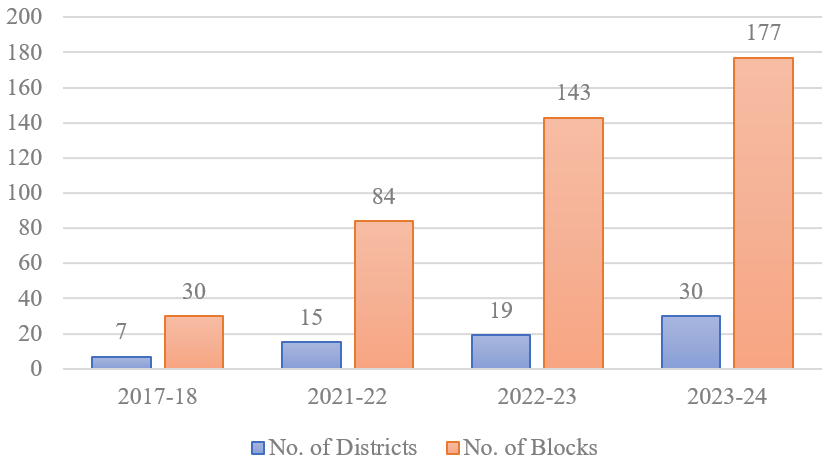

OMM started in 30 blocks of 7 districts, and it recently received approval to be scaled up to 177 blocks in 30 districts (see Figure 1). The rapid geographical spread within a short period of time indicates the success of the programme and its state-wide acceptance. On the basis of the available secondary data, and discussion with some Civil Society Organisation (CSO) members working directly in the field for the implementation of the programme, we highlight the extent to which the policies helped to increase the production and productivity of the millet; how the policies contributed to increased marketing and consumption of the millets; and the challenges it has to overcome to make the programme even more impactful.

Figure 1. Increase in geographical spread of OMM

Prior to 2017, farmers did not cultivate millets as much as rice since there was no assured market for the crop. It was cultivated in small quantities in tribal areas of Odisha for self-consumption by community members. Through OMM, the Odisha government is aiming to boost the whole millets sector by improving its production, processing, procurement, value addition, and consumption.

OMM’s achievements in production and processing

The Odisha government has introduced initiatives for adopting new technologies like line sowing (LS), line transplanting (LT), and system of millet intensification (SMI), and trains CSO members so that they can spread the learning among the farmers. The project demo area has grown from 54,000 hectares (Ha) in 2017 to about 82,000 Ha in 2022. The Mission Secretariat aims to raise this number to an ambitious 150,000 Ha by the end of 2023. CSOs also motivate farmers to produce indigenous millet crops and encourage and train farmers to use natural fertilisers and pesticides for soil health improvement.

The government is also incentivising millet production by declaring monetary support to cover the input costs. As per the Operational Guidelines for OMM, 2022-2026, the amount of assistance is currently Rs. 14,500/Ha over three years for adopting SMI and Rs. 7,250/Ha over three years for LS and LT. Community resource persons (CRPs) identify farmers who would be producing millets, and after field verification, the money is released directly to the farmers’ accounts. The government has taken the initiative to start Custom Hiring Centres (CHC) managed through women-led SHGs and FPOs. CHCs are basically agri-equipment storage points and farmers can take equipment from there at nominal rents. To increase the productivity of millets, community seed centres are also established where the Participatory Varietal Trial method is applied using eight types of local and one government released high yielding variety seeds to find out the three best types of seeds to be used in a particular area.

Due to the adaptation of these better agronomic practices, the productivity of ragi (finger millet) has increased after the implementation of OMM. According to a member of JanaSahajya, an Odisha-based NGO, before adapting new techniques the productivity of ragi reached 5 quintal/acres at most – this has now increased to up to 10 quintal/acre in some areas.

The processing of millets has also become more efficient and there has been a reduction in drudgery, especially for women who are involved in labour-intensive processes. After the introduction of OMM, the usage of machines like ragi thrashers, cleaners, destoners, pulverisers etc. were encouraged1, and they were made accessible through decentralised processing units which were set up not only at the gram panchayat level, but also in some villages depending on the demand.

Improvements in procurement and consumption

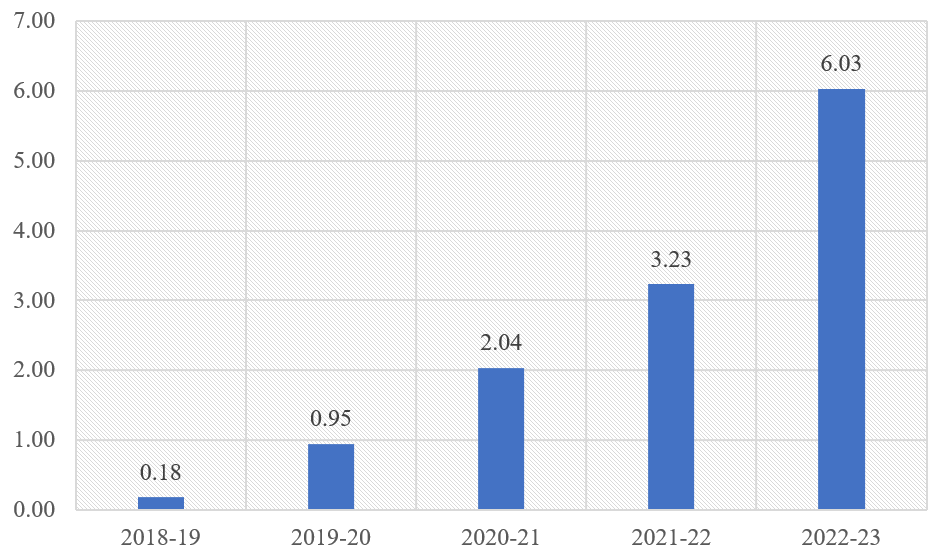

Before OMM was introduced in the state, people mainly produced millets for self-consumption. However, there has been a significant amount of procurement by the government in recent years. The government started procuring ragi under OMM in 2018-19, and by 2021-22, a total of 639,614 quintals of ragi had been procured. In 2022-23, the procurement jumped to around 603,349 quintals in a single year (Figure 2), and the state government is planning for even more procurement in the current year.

Figure 2. Quantity of ragi procured by the government (in 100,000 quintal)

Millet mandis for procurement of the crops have also been started by the government. Farmers have the register through the Millet Procurement Automation System app (or MPAS) to sell their produce to the Tribal Development Co-operative Corporation of Odisha Limited (TDCCOL), which procures ragi from the farmers at better prices. While earlier they were getting Rs. 10-15/kg for ragi in the open market (when in fact, the government procurement price was Rs. 19/kg), the procurement price of the TDCCOL is around Rs. 38/kg now. The amount for the quantity sold goes directly to the farmers’ accounts. The increase in procurement price of ragi has increased prices in the open markets too. Farmers who are not registered in the app, and who sell their produce to the middlemen in the open market, now receive around Rs. 25/kg.

The government has also taken initiatives to popularise millet-based products for consumption by supporting the invention of new and interesting recipes for millets; sponsoring the set up of millet cafes and outlets; and organising food festivals and road shows to increase awareness about millets. The inclusion of millet-based food in mid-day meals is also being encouraged. All these efforts resulted in some awareness creation for millets in the state. PDS offtake of ragi has increased considerably over a short period of time. Between 2019-2021, 109,629 quintals of ragi were distributed to 50.6 lakh ration card holders in the state. The OMM Dashboard shows that in 2022-23, this increased to 402,500 quintals of ragi and it was distributed to 1.13 crore ration card holders. That is to say, within two years, the PDS offtake of ragi saw an almost 3.6 times increase in quantity.

Challenges of implementing the Mission

We know that there is widespread acceptance of the programme, as evidenced by the increased procurement and PDS update. OMM also addressed some social issues, like ensuring the participation of women in the programme and improving the situation of women within the family and community. However, it also faced challenges in implementation. While some of them have been addressed, some still need attention.

After discussion with the CSO members working in the field, we learned about the main challenges encountered during OMM’s implementation. Convincing farmers to adopt better agronomic practices took time, although the early set of results helped garner better interest. The processing of millets was also very labour-intensive. There has been an effort from the government to overcome these barriers, but still much can be done in this area. More research on processing and machinery is needed.

Administrative processes can also be improved. Money transfers can take up to ten days after procurement due to procedural as well as technical issues; this needs to be reduced for farmers to maintain interest. For registering on MPAS, having a land record is necessary, and those who do not have land records to their name cannot register and have to sell to middlemen at a price lower than the Government procurement price.

A considerable number of CSOs were not utilised for a delivery-oriented programme like OMM where targets and achievements are compared, as CSOs were more experienced in executing mobilisation-oriented programmes2. However, with proper training and capacity building, and through a deeper and more long-term engagement that existed between CSOs and the communities, this challenge is being addressed successfully. This has led to CSOs becoming a part of the government procurement process, and also being able to raise their own funds for programme implementation now. Training a huge number of field and other teams involved in the programme was also a Herculean task. Even after standardising the protocols, reaching out to 62 different communities in different languages and dialects proved to be very difficult. It was addressed mainly by getting the systems of operation in place, designing FPOs to act as procurement agencies, and increasing the number of posts for inspection tasks.

There is still not enough awareness about the nutritional values of millets among common people. It is largely seen as the diet for ‘poor people’ in most areas. In some cases, as came through from the discussion with the CSO members, people hesitated in adopting millets as a staple cereal because of its coarse appearance. This mindset needs to be changed, and people can be encouraged to shift from a rice-based diet to a millet-based diet.

How Covid-19 impacted the Mission

The Covid-19 pandemic seriously affected the implementation of OMM. Training programmes were not allowed to be conducted during the period from March-June 2020. CSOs could not spend the amount required for ensuring the next phase of funding, and smaller grassroots-level CSOs were cash strapped. Due to various restrictions to halt the spread of the virus, sowing was affected, and procurement was delayed. Covid also took the lives of several field-level and senior management staff, leading to an overall low morale of the cadre, and requiring the reorganisation of teams. Delays in training, methodical cultivation and procurement, as well as issues with documentation, monitoring, financial diligence and systematic operations led to weak implementation of the programme during the Covid period.

However, despite all the hindrances, the programme absorbed the shocks because of rigorous training systems and processes that had been put in place during the initial phases of the Mission. Targets had to be reassessed to allow for increased flexibility in time and numbers. They were approved by the government authorities in a rapid and timely manner, and OMM eventually came back on its feet around July 2021.

Way forward

The Odisha Millets Mission has achieved a lot in the six years since its implementation. This is more impressive when we consider that in three of those six years, the world was going through a pandemic. The success of its implementation has received acknowledgement from the Government of India, and OMM was encouraged to be taken as a model for promotion of millets, pulses and oilseeds in other states. OMM has been successful in attracting international attention – both the IFAD and the FAO have supported the programme as being suitable to address agro-ecological issues. In November 2023, the Odisha government is hosting International Convention on Millets in Bhubaneswar.

As the Odisha Millets Mission has progressively grown, it has opened up opportunities for investing in more human resources, and in rigorous research and development towards improved and ergonomically suitable machinery. The increased scale also demands timely and efficient maintenance of existing machinery.

A shift in the perception of millet from being a poor person’s food to one of abundant nutritional value, while being cost-effective and environmentally sustainable at the same time, would encourage more people to consume millets. An emphasis on changing mindsets would augment the ongoing process towards increasing demand and offtake.

Ragi is a large component of the millet mix being procured at the moment. The government increasing the diversity in the procurement mix would increase the opportunity for diversity in cultivation at the farmers’ ends. This step will help maintain the indigenous variety of millets. Multi-cropping with pulses should also be encouraged, since the cultivation of pulses ensures seasonal nitrification and aeration of the soil by natural means, and increases the nutritional diversity on the plate. Along with this, sharing knowledge and learning across different geographical areas of the state can play an important role in improving the implementation of the programme.

OMM has become a model programme for other states of India to follow. For example, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra did not have any programme focused on millets despite being two states which produce considerable amounts of millet crops. Taking inspiration from OMM, Chhattisgarh started their own millet mission in 2021 and Maharashtra launched theirs in 2023. Assam has also started their millet mission in 2022. This comes with more responsibility for the Odisha government to keep up the work it has been doing in this regard. The Mission is currently extended till 2026, with support from the Odisha Chief Minister’s office which has asked the Mission Secretariat to prepare a roadmap for the coming ten years.

Going ahead, this model has the potential to address the nutritional security issues of the country, especially for the vulnerable and marginalised population. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to properly document and evaluate the impact of this programme, and to scale it up to other states for nutritional, economic and environmental impact.

The authors would like to thank Diksha Satyawali, Dinesh Balam, Sita Devi, and Prakash Mallick for discussion and insights that contributed to developing this article.

Notes:

- It is mentioned in the Operational Guidelines for OMM, 2022-2026 that FPOs/ SHGs will be supplied with processing, cooking and packaging machinery costing between Rs. 200,000-300,000. It is also mentioned that a part of the budget for experimentation and innovation allocated to the Programme Secretariat will be used for development and demonstration of machinery related to millets.

- The traditional approach of the NGO sector has been to mobilise communities through long-term handholding and awareness campaigns. This approach alone is incomplete – when augmented with the delivery-oriented model of measuring targets and achievements, it has produced clearer results.

23 October, 2023

23 October, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.