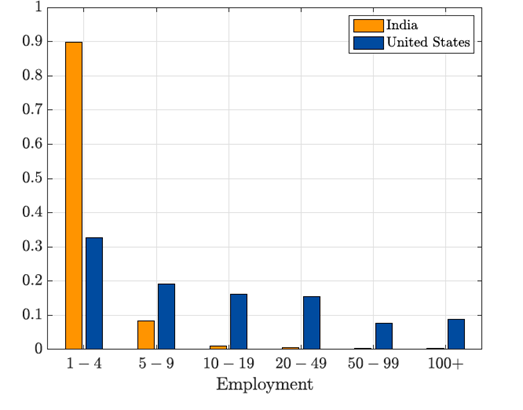

In this post, Peters and Zilibotti compare the size of firms in India and the US, and find that the 90% of firms in India have four employees or less, and attribute it to the absence of creative destruction. They consider that creative destruction in India may be lower due to high costs of entry or expansion, or the prevalence of ‘subsistence entrepreneurs’ and highlight the need for different policies at different stages of development.

How do countries grow? There is a long-standing conjecture that the answer to this question differs between high- and low-income countries. One influential narrative, developed in Acemoglu et al. (2006), holds that rich countries close to the technological frontier rely on innovation and creative destruction1, while developing economies generate most of their growth through the imitation and adoption of technologies already used in advanced economies.

Understanding these different patterns of growth is not only of academic interest, but has important practical implications: different policies and institutions may be optimal at different stages of development. In developing countries behind the technological frontier, economic growth may be aided by government interventions that selectively support specific firms and industries in adopting existing technologies. These practices often impose implicit or explicit barriers on the entry and growth of new firms, and so they might be detrimental to competition and creative destruction. However, if growth is mostly adoption-based, the benefits may outweigh these costs.

But as an economy approaches the technological frontier, such policies eventually become a burden on further development. At that point, countries must introduce economic reforms to liberalise entry of new firms and foster creative destruction to sustain economic growth.

Existing studies exploit aggregate cross-country data to provide evidence on various qualitative predictions of this narrative (see, for example, Zilibotti (2017) or Vandenbussche et al. (2006)). In a new study (Peters and Zilibotti 2022), we demonstrate how readily available firm-level data can be used to test additional implications and perform quantitative policy analysis.

The creative destruction view of economic development

Firms in rich and poor countries look strikingly different. In developed economies, the firms that perform the lion’s share of aggregate economic activity are, on average, large, and grow as they age. In low-income countries, by contrast, the firms that account for most of what the economy produces are small and stagnant.

Figure 1 demonstrates this by comparing firms in India and the US. In India, 90% of firms have at most four employees and only a negligible fraction of firms employs more than 100 workers. In the US, only one-third of firms have less than five employees, while almost 10% of them have more than 100 employees. In short, an organisation of economic activity in which a sizable share of the labour force works in large corporations is a rich-country phenomenon.

Figure 1. Firm size distribution in India and the United States

Sources: i) For India: Annual Survey of Industry and National Sample Survey. ii) For the United States: US Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics

Firm size: Ubiquitous constraints or lack of creative destruction?

Figure 1 can be interpreted in two ways. The first, traditional view is one of ubiquitous constraints – the existence of the many small firms in India is a sign that such producers face insurmountable challenges to expand. Such constraints can stem from various forms of market imperfections: imperfect credit markets limiting productive investments; imperfect labour markets preventing (some) firms from increasing their productive scale; and product markets being characterised by frictions where, for example, trade costs keep firms from acquiring customers. The second, more novel view is what we call the creative destruction view. It argues that the large number of small firms in India is a symptom of the absence of creative destruction: small firms manage to survive because bigger firms are not replacing them quickly enough.

These two views have very different implications for optimal growth policies. According to the traditional view, small firms are too small, and policy should extend subsidies to help them grow. According to the creative destruction view, small firms are too large – ideally, they should not exist at all! In either scenario, it might not be the small, informal producers that face constraints that limit the size of their operation. Rather, firms in the middle of the firm size distribution might face the most expansion hurdles, preventing them from growing and forcing small firms to exit.

In our study, we provide evidence in favour of the creative destruction view. In particular, we show that creative destruction is indeed much lower in India compared to the US. This conclusion is based on a simple insight. In the data, India has a much higher share of small firms, as is evident from Figure 1. At the same time, the aggregate exit rate – meaning the rate at which firms go out of business – is almost identical between the two countries. Hence, Indian firms exit at similar rates as firms in the US despite the fact that they are very small. This suggests that the extent of churning and creative destruction in India has to be small.

Creative destruction as a cause and consequence of economic development

Why is creative destruction low in India? In our paper we consider three hypotheses that may well coexist. First, new firms could face high entry costs in India. Second, existing firms could face large costs to expand. Third, building on Akcigit et al. (2021), we allow for the possibility that many firms in India are run by ‘subsistence entrepreneurs’ who opened businesses not to expand them in search of economic opportunities, but rather out of necessity given the absence of stable jobs.

The interplay between these three forces highlights that creative destruction is both a cause and a consequence of economic development. On the one hand, creative destruction is a necessary ingredient for subsistence firms to exit. As such, it reallocates resources to transformative entrepreneurs who can use them more productively. But if entry and expansion costs are high, this reallocation process cannot take place. On the other hand, if the majority of firms are subsistence producers, creative destruction is bound to be low, as there are simply too few transformative firms with growth potential to meaningfully affect the process of selection at the aggregate level.

While all three mechanisms could contribute to lower creative destruction in India, they leave very different traces in the data. We show they can be separately identified from readily available information such as firm exit rates, firm size distribution, and the extent of life-cycle growth. To summarise: India has a much higher share of subsistence firms than the US, and existing firms in the US face much lower frictions to expand. Meanwhile, entry costs (relative to the wage) are roughly of the same size in both countries

Implications for development policy

This finding has important implications for industrial policy. Some countries like the US have few subsistence entrepreneurs, and existing firms can expand seamlessly. In these countries, creative destruction is high, firms are large, and productivity growth is mostly driven by innovation. Other countries such as India have fewer firms with growth potential, and these firms face higher barriers to increase their scale. As a consequence, creative destruction is low, firms are small, and aggregate growth is driven mostly by the adoption of technologies developed in the US and other developed countries.

These differences imply the need for a different policy-mix to achieve higher living standards. In particular, growth would be higher if economic activity could be reallocated to transformative firms. Does this imply that there is a role for the government to protect transformative firms? It turns out that the answer is: it depends. On the one hand, government protections increase the market share of transformative firms and encourage these firms to expand. On the other hand, such policies also have detrimental effects by blocking some innovations: such forms of protection reduce the expected returns to innovation because firms anticipate that a share of their ventures will be blocked.

Importantly, the relative importance of these considerations differs between the US and India. In the US, where most firms are transformative, this firm of protection is a blunt instrument, and the negative consequences will likely dominate. By contrast, in India, where transformative entrepreneurs are an endangered species, such policies can increase wages, growth and welfare.

This article has been published in collaboration with VoxDev.

Note:

- Creative destruction refers to process of innovation by which new production units with a superior technology replace existing producers.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, Philippe Aghion and Fabrizio Zilibotti (2006), “Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(1): 37-74.

- Akcigit, Ufuk, Harun Alp and Michael Peters (2021), “Lack of Selection and Limits to Delegation: Firm Dynamics in Developing Countries”, American Economic Review, 111(1): 231-75.

- Peters, M and F Zilibotti (2022), ‘Creative Destruction, Distance to Frontier, and Economic Development’, prepared for "The Economics of Creative Destruction - A Festschrift in honor of Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt" (forthcoming). An earlier version of this paper is available here.

- Vandenbussche, Jerome, Philippe Aghion and Costas Meghir (2006), “Growth, distance to frontier and composition of human capital”, Journal of Economic Growth, 11(2): 97-127.

-

Zilibotti, Fabrizio (2017), “Growing and slowing down like China”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(5): 943-998.

27 January, 2023

27 January, 2023

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.