It is well-established that treated water has health benefits, but can it also enhance children’s educational outcomes? Analysing India Human Development Survey data, this article provides evidence in this context – identifying pathways such as decreased incidence of diarrhoea, lesser time spent on fetching water, and reduced expenditure on short-term morbidity allowing for higher spend on education. Further, the impact is more pronounced for girls.

Poor quality drinking water poses significant health risks, and could result in severe health problems such as diarrhoea, dysentery, typhoid, and cholera, contributing to high morbidity and mortality rates (Jalan and Ravallion 2003, Kosec 2014). A 2021 UNICEF report reveals that one-third of the global population lacks access to clean, safe drinking water, and over 700 children under the age of five die daily from diarrhoeal diseases caused by unsafe water and inadequate sanitation. These health issues are more prevalent and concerning in developing countries, especially in the wake of climate change and groundwater depletion affecting the supply of fresh water. Noting the detrimental effects of unsafe drinking water, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 emphasises the provisioning of “clean water and sanitation for all”. However, as of 2020, around 2 billion people worldwide use drinking water contaminated with human waste (World Health Organization, 2022). Thus, supplying safe drinking water to households has become a policy priority to ensure better public health.

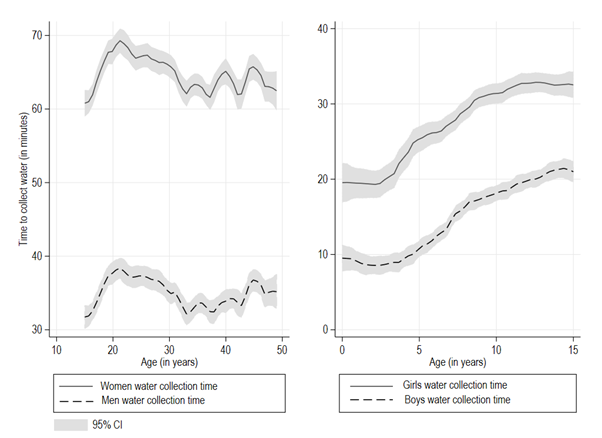

Access to indoor piped drinking water (henceforth IPDW) can be highly beneficial for women and girls in particular. Figure 1 shows that women spend considerably more time on collecting water for household needs as compared to men. Such unproductive time use adversely impacts girls’ educational outcomes and reduces the time available to women for other activities such as income generation, childcare, and household chores (Choudhuri and Desai 2021, Zhang and Xu 2016).

Figure 1. Daily time spent on water collection, by gender

Source: Author’s computation using data from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) (2004, 2011)

Note: A 95% CI (confidence interval) means that if you were to repeat the experiment over and over with new samples, 95% of the time the calculated CI (in grey) would contain the true effect. A CI is a way of expressing uncertainty about estimated effects.

Against this backdrop, we examine the impact of India’s flagship drinking water supply programme, called the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP), on children's educational and learning outcomes.

Context

In 2009, the central government launched NRDWP across all rural regions in India. The primary goal of NRDWP was to supply IPDW to all rural households. The programme emphasises potability, adequacy, convenience, affordability, and equity in access to safe drinking water. Under the NRDWP, each rural household receives a daily per capita supply of 40 litres of water, designated for specific purposes such as drinking, cooking, and other domestic necessities. The quality of IPDW supplied under NRDWP complies with the Indian standard for drinking water (IS-10500) set by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), and such supply is free from biological contaminants and harmful chemicals. The NRDWP guidelines were further revised to entrust the local Panchayati Raj institutions with the responsibility of ensuring last-mile delivery of the water supply services.

Data and methodology

We use data from nationally representative survey rounds (2004 and 2011) of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS). Our sample comprises children aged 8-11 across 27 states and six union territories in the country. Our educational outcome variables of interest are whether the child is enrolled in school, and child-specific educational expenditure incurred by parents. In terms of learning outcomes, we focus on children’s reading ability and math skills.

We employ the ‘difference-in-differences’1 methodology to estimate the causal impact of the NRDWP on educational and learning outcomes of children. Our hypothesis is that children in villages with lower initial IPDW access levels are likely to gain more from the programme than their counterparts in villages with higher initial access levels. Therefore, we exploit variation in the village-level IPDW intensity at the baseline (2004) to define ‘treatment’ (lowest quartile of IPDW intensity) and ‘control’ (highest quartile of IPDW intensity) villages. Subsequently, we compare changes in average outcomes of children residing in treatment and control villages between pre- and post-intervention periods (2004 and 2011 respectively) to estimate the impact of the NRDWP programme.

Findings

Our findings indicate a 4.5% increase in overall enrolment, and a surge in child-specific educational expenditures by 14% in villages that were in the lowest quartile (treatment), relative to villages in the highest quartile in terms of baseline IPDW intensity (control).2 Additionally, we observe a 6.3% improvement in the ability of school children to read a paragraph and 20% improvement in the ability to read a story, in treatment villages as compared to control villages.

Turning to the mechanisms through which these improvements in educational outcomes take place, our results suggest a 50% decline in the average time women spend fetching water, of five minutes per trip on average. This, in combination with increased safety and lower incidence of diseases, leaves more time which women can productively utilise on other activities such as income generation and childcare. By the same token, girls are also able to spend more time on education. Consequently, we find evidence of a significant increase by one and two hours in time spent on homework and private tuition, respectively.

We also find evidence of significant health and other benefits of IPDW for children in terms of a 4 percentage point decrease in diarrhoeal cases, and 2.5 fewer days of school absenteeism in a month. We examine whether the improved water quality has led to a reduction in short-term hospital expenses, such as those incurred on account of diarrhoea. We observe a significant 38.2% reduction in short-term morbidity expenses in the treatment villages, equivalent to a 44% decrease in average short-term morbidity expenditure. While access to IPDW improves time-use outcomes for girls, contributing to better educational outcomes, the fall in incidence of diarrhoea and decreased morbidity also positively affects the learning outcomes of boys.

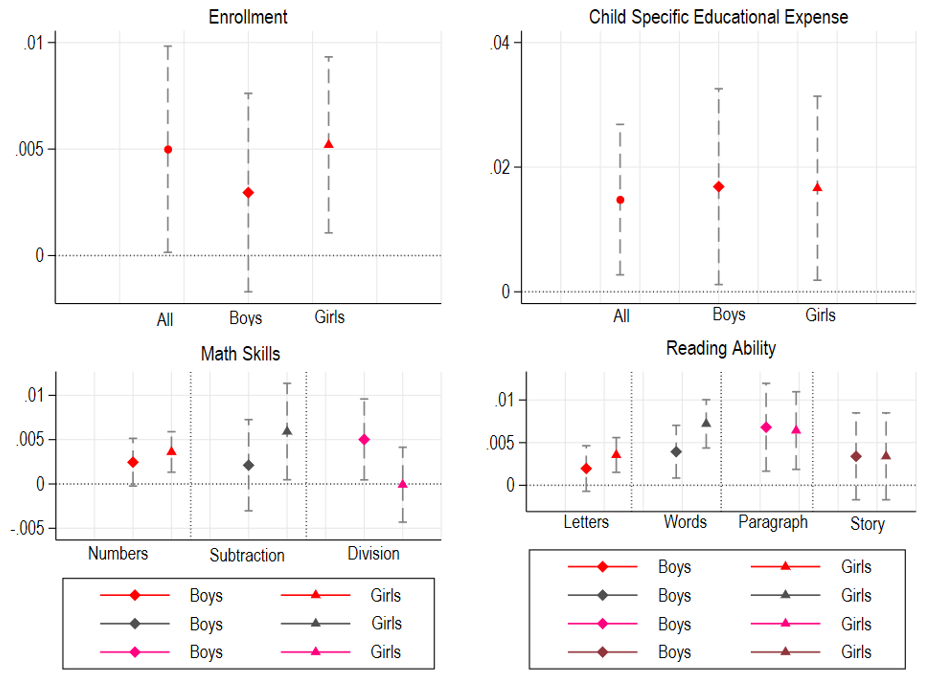

We also analyse the impact of the programme using an alternative econometric specification in line with the ‘intensive margin approach’.3 We examine the effect of the number of hours of IPDW supply on the educational and learning outcomes of rural children aged 8-11. To this end, we regress our outcome variables on the number of hours of IPDW supply (ranges from 1 hour to 24 hours) and estimate a ‘pooled regression’ with demographic, socioeconomic control variables and any unobserved effect emanating from different survey rounds. We present the point estimates of the impact of hours of IPDW supply on the outcome variables for the full sample, boys and girls in Figure 2. Most of the estimates are statistically significant (zero not being included in the confidence interval) suggesting that the duration of IPDW supply positively impacts educational and learning outcomes.

Figure 2. Impact of hours of IPDW supply on educational and learning outcomes of rural children aged 8-11

We conduct a battery of ‘robustness checks’, which includes placebo tests. First, we restrict the sample to urban regions and find similar results. Second, we examine the impact of access to IPDW supply on non-waterborne diseases, and find no evidence of IPDW affecting the outcome variables. Additionally, we control for other potential confounding factors such as access to electricity, toilet facilities, and distance to schools, which can also influence our outcome variables. Our results suggest that the above-mentioned factors do not drive our impact estimates.

Policy implications

In many households, women are primarily responsible for water collection for the entire household. Absence of a clean and safe source of drinking water compels women and girls to spend substantial time on fetching water. This type of time use further exacerbates intra-household gender disparities in terms of access to health and education. Thus, providing IPDW through a nationwide programme such as NRDWP can serve twin objectives. First, it can ensure equity in access to safe drinking water and hence, lead to better health of rural households in India. Second, NRDWP can pave the way for closing gender gaps in education and aid the empowerment of women in rural India.

Notes:

- In a standard difference-in-differences framework, longitudinal data is used to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups, where one was impacted by an event or policy – in this case, access to IPDW through NRDWP – while the other was not.

- All percent changes are computed by dividing the point estimates of the impact of NRDWP on outcome variables by the corresponding mean (average) of the outcome variable in question.

- Simply put, in this context, intensive margin approach hypothesises a direct relation between number of hours of IPDW supply availed and educational and learning outcomes of children belonging to households with access to IPDW at their dwelling units.

Further Reading

- Choudhuri, Pallavi and Sonalde Desai (2021), “Lack of access to clean fuel and piped water and children’s educational outcomes in rural India”, World Development, 145: 105535.

- Jalan, Jyotsna and Martin Ravallion (2003), “Does piped water reduce diarrhea for children in rural India?”, Journal of Econometrics, 112(1): 153-173.

- Kosec, Katrina (2014), “The child health implications of privatizing africa’s urban water supply”, Journal of Health Economics, 35(1): 1-19.

- World Health Organization (2022), ‘State of the world's drinking water: An urgent call to action to accelerate progress on ensuring safe drinking water for all’, Report, WHO, UNICEF, World Bank.

- Zhang, Jing and Lixin Colin Xu (2016), “The long-run effects of treated water on education: The rural drinking water program in China”, Journal of Development Economics, 122: 1-15.

20 February, 2024

20 February, 2024

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.