Bars provide on-premise alcohol consumption and serve as social drinking spaces. Kerala, in 2014, shut down all bars serving hard liquor in the state. This article examines the policy change and whether it had any impact on the risk of violent crimes against women outside their homes. It finds that post the change in regulation, the reported incidence of sexual assaults against women came down by 25% while no discernible effects were found on rape.

Alcohol consumption is often considered a mediator in commitment of crimes. The link stems from impaired cognitive functioning under intoxication. In a survey conducted under Safe City Initiative by Jagori and UN Women in 2010, 50% of women in Delhi reported consumption of alcohol by men as a threat to their safety outside home. There is a large body of evidence across countries that shows a higher propensity to commit crime and increased accidental mortality under the influence of alcohol (see Carpenter and Carlos (2010), Carpenter and Dobkin (2011) for a review of studies). However, evidence on crimes against women is limited.

Regulating alcohol consumption and crimes

Quasi-experimental studies usually examine the impact of public policy instruments like alcohol taxes, density of liquor stores, prohibitions and Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA), on crimes. In the Indian context there are two studies – Luca et al. (2015) and Luca et al. (2019) which show that imposition of alcohol bans and higher MLDA in India significantly reduce reported incidence of domestic violence and sexual harassment of women.1

Globally, there is limited evidence on social drinking and its effects on crimes against women. Anderson et al. (2018) find that an increase in bar densities in Kansas state in the US, led to an increase in reported incidents of rape, robbery and general assaults. Biderman et al. (2009) show that early closing of bars reduced homicides in Sao Paulo Metropolitan area of Brazil. From a public policy perspective, it is important to understand which types of regulations are effective and on what crimes, since safety of women is a pertinent issue.

Policy background: Kerala’s regulation change

Over the last few decades, many states in India have prohibited the sale of alcohol – Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Mizoram, Orissa, Tamil Nadu – and then repealed the bans. The recent discourse in India has again upped the battle against liquor consumption. Bihar prohibited it completely in 2016. Tamil Nadu has started a gradual closure of liquor shops from 2016 onwards. In 2014, Kerala cracked down on hard liquor sale and consumption in its local bars.

The political economy considerations behind the regulation change in Kerala were internal party politics within the United Democratic Front (UDF) government, the corruption allegations by the opposition, and the risk of being seen as favouring the liquor lobby for the Chief Minister. Consequently, the UDF government passed a legislation which aimed at complete alcohol prohibition in the state by 2023. As a first step, the government of Kerala shut the local bars selling hard liquor; only bars in five-star hotels were allowed to sell it. This led to closure of 418 bars whose licenses were not renewed in April 2014. In total 730 foreign liquor bars run by private hoteliers and 10% of total outlets of government-run retail shops were shut down by August. There was no effect of the ban on toddy (a mildly alcoholic, locally brewed beverage), wine and beer shops. Many of these bars reopened as wine and beer parlours.

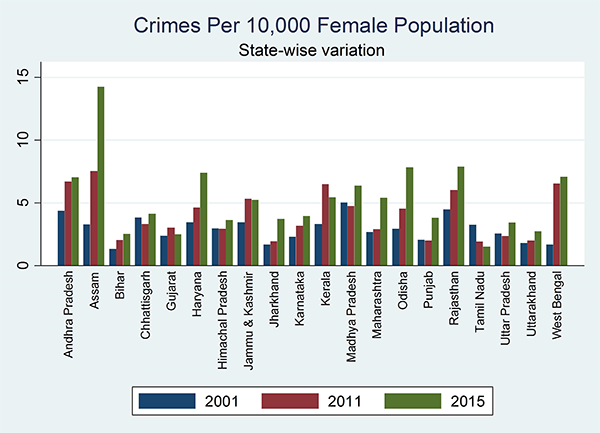

Kerala is one of the most developed states in India and is also among the top five states in reported incidence of crimes against women, likely due to better reporting. Crime rate against women stood at 3.33 in 2001 and at 6.50 in 2011 but in 2015 the incidence of such crimes had fallen in the state (Figure 1). Kerala’s per capita annual consumption of all types of alcohol by adults was also higher than the national average in 2011 (Vidhukumar et al. 2016). It is important to understand whether the regulation change around liquor bars in Kerala led to this decline in crime.

Figure 1. State-wise total crimes against women for the years 2001, 2011, 2015

The immediate consequence of this policy shift in Kerala was an increase in cost of access to hard liquor and consequently a reduction in consumption of hard liquor in the state by 18% from 2014-15 to 2015-16 (Kerala State Beverage Corporation). There was also a simultaneous substitution towards beer. Although the alcoholic content of beer is lower, ex-ante it is not clear if such a regulation change would have any effect. If men substitute towards beer and acquire the same level of inebriation as without regulation, then there may be no effect. Also, increased drinking at home can cause a spurt in domestic violence. On the other hand, reduced inebriation in bars can also reduce domestic violence. Hence, we also look at the effect on reported incidence of domestic violence.

Assessing the impact

We collate district-level panel data on reported crimes for the years 2010-2015. The years before the regulation was imposed are referred to as the pre-‘treatment’ years (2010-2013) and the years after it was imposed are referred to as the treatment years (2014-2015)2. We use a difference-in-difference estimation strategy3 (using neighbouring states as a ‘control’ group) to study the effect of this policy change on crimes against women like sexual assaults and rapes. We compare the average reported crime changes for the districts of Kerala (treatment) to those lying on the border of Kerala in the neighbouring states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu (control), controlling for linear trends in crime reporting.

The treatment intensity varied by district within Kerala since the existing stock of bars was different. We use this additional information to check if crime reduction was greater in districts where more bars were shut down.4

Findings

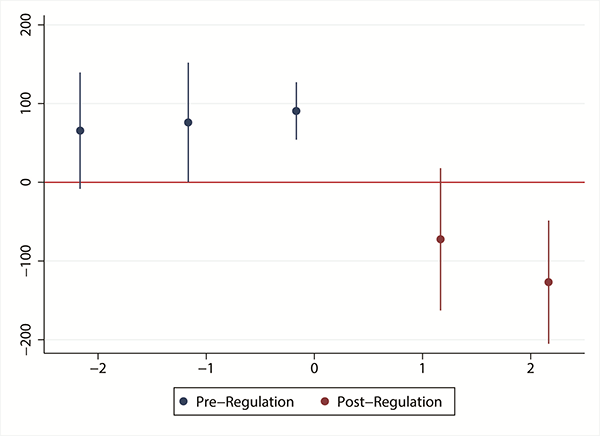

We find that there is a significant reduction in sexual assault cases reported by women post the closure of hard liquor bars by 73 incidents per district, that is, approximately 25% (as a proportion of baseline average). These results become stronger (30% reduction) when we control for changes in police and income per capita over time. Figure 2 shows the year-wise effects for the pre- and the post-treatment years. Clearly, there is no decrease in sexual assaults in the pre-treatment years and it only kicks in post the regulation change.

Further, the reduction in sexual assaults is greater in districts where a larger number of bars (per 100,000 population) were shut down. We also observe a reduction in eve teasing and rapes, but the effect is imprecise. There is no effect of the policy change on domestic violence. The results from an alternative estimation method, where the control group is chosen using data-driven methods, confirm our previous findings regarding reduction in sexual assaults post the regulation change.5

Figure 2. Event study plot: Sexual assaults against women

Mechanisms

We hypothesise that the main mechanism resulting in the reduced incidence is a decreased likelihood of interpersonal interactions between a potential victim and an inebriated perpetrator after the regulation change. Another potential mechanism can be a general reduction in crimes in Kerala after 2014. Our estimates, varying by initial consumption and treatment intensity, and estimation of effects on other crimes cast doubt on the second mechanism.

First, we find a greater reduction in sexual assaults in districts with higher level of initial hard liquor consumption and larger number of bars closed down. Second, we examine the effect on other crimes like hurts, theft, burglary, kidnapping, and murder. The only significant reduction is in hurts, which mostly captures incidents of physical assaults that occur during fights. These brawls are more likely to happen under influence of alcohol, especially in a group.

Conclusion

In this study, we examine the effect of reduction in hard liquor availability in social spaces like bars, on crimes committed against women in public spaces. Since bars serve as on-premise drinking spaces in public areas, drinking in bars can increase the probability of social contact between a likely perpetrator and a potential victim. This can result in an increase in sexual assaults experienced by women in public areas. The regulation change considered in this study is likely to lower social drinking outside the home resulting in a decreased likelihood of interpersonal interactions under an inebriated condition. We show that placing restrictions on alcohol sale through closure of on-premise drinking outlets that serve hard liquor reduces reported incidence of sexual assault and harassment against women.

Notes:

- A recent unpublished study by Dar and Sahay (2018) evaluates the effect of alcohol ban imposed in the state of Bihar in India on general violent and non-violent crimes.

- The latest year for which crime data is available is 2016, but we limit the analyses presented in the main paper to 2015. This is because one of the neighbouring states of Kerala, namely Tamil Nadu, started a phase-wise closure of liquor vends in 2016. The conclusions, however, do not change when data for year 2016 is incorporated.

- A technique to compare the evolution of outcomes over time in similar groups that gained access to an intervention with those that did not.

- We also verify the robustness of our results using synthetic control construction methods (Abadie et al. 2010). In this method, instead of taking bordering districts and states as the control group, we allow data to give the control districts based on the ones that match the trends in crimes in districts of Kerala, before the bars were closed down.

- This method also shows a significant decline in domestic violence in Kerala post 2014.

Further Reading

- Abadie, Alberto, Diamond Alexis and Jens Hainmueller (2010), “Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California's tobacco control program”, Journal of the American statistical Association, 105(490):493-505.

- Anderson, D Mark, Benjamin Crost, Daniel I Rees (2018), “Wet Laws, Drinking Establishments and Violent Crime”, The Economic Journal, 128(611):1333-1366.

- Biderman, Ciro, João MP De Mello and Alexandre Schneider (2009), “Dry laws and homicides: Evidence from the São Paulo metropolitan area”, The Economic Journal, 120(543):157-182.

- Carpenter, C and C Dobkin (2010), ‘Alcohol regulation and crime’, NBER Chapters in, Controlling crime: Strategies and tradeoffs, University of Chicago Press, Pages 291-329.

- Carpenter, Christopher and Carlos Dobkin (2011), “The minimum legal drinking age and public health”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(2):133-56.

- Dar, A and A Sahay (2018), ‘Designing Policy in Weak States: Unintended Consequences of Alcohol Prohibition in Bihar’. Available here.

- Luca, Dara Lee, Emily Owens and Gunjan Sharma (2015), “Can alcohol prohibition reduce violence against women?”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 105(5):625-629.

- Luca, Dara Lee, Emily Owens and Gunjan Sharma (2019), “The effectiveness and effects of alcohol regulation: Evidence from India”, IZA Journal of Development and Migration, 9(1):4.

- Vidhukumar, K, E Nazeer and P Anil (2016), “Prevalence and pattern of alcohol use in Kerala-A district based survey”, International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology, 18(2):363-367.

25 November, 2019

25 November, 2019

Comments will be held for moderation. Your contact information will not be made public.